by Anonymous on 3/22/2008 10:02:00 AM

Saturday, March 22, 2008

A Tale of Real Estate Predation

I recommend this story in this morning's Washington Post, "My House. My Dream. It Was All an Illusion," by Brigid Schulte. It's a good article, although I'm going to offer some criticism. I know; you're all shocked.

As is so often the case, I find these stories hard to read. For one thing, there's that habit reporters have of just not recapitulating a complex narrative in order. This story isn't as bad as some in that regard, but there's still this habit of breaking off the narrative to get a quoted generalization from an expert or just generalizations provided by the reporter that break the narrative flow. On a story this complicated, it would help to try to avoid that.

The other problem is that I end up not being sure the reporter is using terminology terribly accurately. Is this nitpicky? Not if the idea of these stories is to help people spot similar scams in the future, should they be so unfortunate as to run into one. For instance, part of this scam seems to involve a homebuyer convinced she was making a "down payment" when it appears she was only covering (excessive) closing costs. It doesn't help much for the reporter to perpetuate the confusion by continuing to refer to a "down payment." I think most consumers believe that a "down payment" translates into "equity." If all you are doing is paying closing costs, you are starting out with zero equity (100% financing). We need to be making this clearer, not falling into the trap.

But there is also one ringing silence in this story--it's something I see in 99% of these kinds of news stories, and frankly I'm getting tired of it. Let me do my usual re-cap of the narrative, and see if you all can hear the dog that didn't bark.

In 2005 Glenda Ortiz fell afoul of a fast-talking door-to-door salesperson, Salgado, who besides being a Mary Kay peddler was also a "sales assistant" for a relitter, Aguilar. In this context "sales assistant" means the person Aguilar was paying illegal "referral fees" for reeling in marks. Salgado is not a licensed relitter and both Virginia RE regulations and HUD rules prohibit this kind of "kickback."

Someone--Salgado or Aguilar, it isn't clear--showed Ortiz one house and only one house, a "run-down one story duplex" listed for $425,000. Ortiz ended up signing a contract for $430,000. (In this context, "duplex" appears to mean a single-unit structure that is attached to another single-unit structure with a shared firewall and a lot line running down the middle of the house, not a two-unit structure on a single parcel of real estate.)

Ortiz didn't have the money "for a down payment," and did not have a good credit record, but Salgado offered to lend her "half" of what is said to be an $11,000 down payment and be a joint applicant on the loan (presumably to "bump up" the qualifying FICO by using Salgado's). (Unmentioned in the story: half of $11,000 would be very nearly the amount of the sales price in excess of the list price, no?) The "deal" Ortiz was presented with is that in "a year," when the house had appreciated by 20% or so, Ortiz would refinance, extract $70,000, and pay half of that to Salgado "for her share of the down payment and for allowing Ortiz to use her credit." Lend someone $5,500, get back $35,000 in a year? Nice work if you can get it.

When Ortiz, whose spoken English appears minimal and who cannot read English, got to the closing in August 2005, she found that Salgado wasn't her "co-buyer," Salgado's brother Hernandez was. Ortiz ended up signing documents that made her the buyer of the home--her name was on the deed along with Hernandez'--but not a borrower on the loan: only Hernandez was actually on the note. (Presumably because only Hernandez "qualified" for the loan.) Ortiz was induced to sign a statement that she was Hernandez' wife, although she seems to have met him for the first time at closing and she's already married to someone else.

Salgado says her own credit wasn't good enough to help Ortiz--there's a surprise--and that she was just "helping out a friend." It appears that "the woman handling the loan" (I don't know if that means the mortgage broker or the title company settlement agent, in context) was the wife of Aguilar, the licensed relitter for whom Salgado worked. Ortiz was told that Hernandez would be taken off the title in one year and she would own the home outright.

The Post got an unrelated mortgage broker to look at the documents on the loan, and he found "junk fees and an overpriced appraisal," with "'excessive' closing costs . . . upward of $10,000." I suspect the appraisal was "overpriced" because someone had to be bribed to bring the value up to the sales price. In any event, this is why I'm a bit befuddled by the reference to the "down payment." It sounds to me like Ortiz paid closing costs of $11,000 or thereabouts, with half of it from Selgado or Hernandez, resulting in a 100% LTV loan.

The reporter says she got a "high interest" loan with a payment of "more than $3,000 a month" that was 70% of Ortiz's (and her real husband's) gross monthly income. I really wish reporters would stop doing things like that--if the point here is to help readers understand what a "high interest" loan is, it would be useful to know what rate it was and for what kind of loan, and whether that "payment" is P&I or PITI (that is, whether it includes taxes and insurance as well as principal and interest). I assume it's P&I only, and using $3,000 as the payment and $430,000 as the loan amount and a 30-year term, I get an interest rate of just under 7.50%. Quite honestly, for a 100% purchase on a nonconforming loan that's not such a bad rate. This frustrates me to no end, as I complain regularly about borrowers who do not understand a rate that is "too good to be true." No doubt it was an ARM and Ortiz didn't know that; possibly it was a 40-year term. But it hardly matters: she couldn't afford the start rate. She could never have been anywhere close to affording the true "risk-based pricing" she'd have gotten if the scumballs hadn't substituted a "straw borrower" in her place. But I don't think we're helping people by giving them the impression that 7.50% or so is a "high rate" for the terms of this deal.

Inevitably, Ortiz couldn't keep up the payments, after having sold belongings, gotten behind on other bills, and borrowed more money to make payments as long as possible. Salgado didn't come through with the promised refi, of course, and when Ortiz tried to work something out with the bank, she only then learned that she wasn't on the note, was not the legal borrower, and hence had no "standing" to work anything out with the lender. When she asked Hernandez to help, "he told her to leave the home."

Ortiz ended up deeding the house over to Hernandez, in an agreement that "prohibit[s] Ortiz from suing Salgado and Hernandez for fraud." She received nothing for having made mortgage payments and paid half the closing costs. Hernandez "sold the home in December [of 2007] for $380,000." There is no mention of who the sucker (or co-conspirator, you never know) was who paid that much for this home. Or who financed it. We talk a lot about short sales and current owners getting out, and we never seem to worry much about who is getting in.

The money quote is from Aguilar the relitter:

Aguilar said he saw nothing amiss in the transaction. Ortiz wanted a house, and Hernandez wanted an investment.Too funny, Mr. Scumbucket. Ortiz wasn't in a bad loan. Ortiz never got a loan. Ortiz got suckered into making someone else's mortgage payments.

"Everybody was fine. Everybody was happy. But now that the market's gone down, everybody's got a problem and wants to blame it on the realtor, saying we guided them to bad loans," he said. "Everybody's blaming everybody else. But everyone contributed to the housing bubble, the banks, the real estate agents, the appraisers. Everyone's to blame."

So what is this missing detail that is driving me crazy? Where's the seller? Who was the seller? Who listed a run-down property for the outrageous sum of $425,000, and then accepted a bid of $430,000 from a buyer whose ability to understand the transaction was pretty clearly dubious and who wasn't represented by an attorney at closing? Why did the relitter (or the "sales assistant") make a beeline for that house, and show Ortiz only that house?

I seriously wonder about this, I guess because I assume (possibly quite incorrectly) that if the original seller had been in cahoots with (or an alternative identity of) the RE agent, we'd have heard about it in the article. I fear that the seller was truly an unrelated party--who may or may not have kicked the $5,000 in excess price to Salgado in order for her to "pay half" the "down payment." I fear this because there is this idea floating around in the world that that makes the seller "innocent."

What's so "innocent" about taking advantage of a naive, uninformed, and unrepresented buyer to profiteer off real estate? We have the word "profiteer" in English, as well as the word "profit," because we have long recognized that there is a difference between simply selling an asset that has appreciated in value, on the one hand, and taking advantage of the desperate on the other. But that distinction simply disappeared during the boom: everybody got behind the idea that it was perfectly "respectable" to screw the next guy in line and not look too closely into the identity or capability of the prospective buyer. It is, of course, not illegal to sign a sales contract with a counterparty whom you know nothing about, and whose capacity to perform under the contract ought to be dubious to anyone with one or two good brain cells. That's just how the free market is, ya know?

We just looked the other day at a case of outright journalistic malpractice in the New York Times, where some hustler who advocates "illegal assumptions" of upside down loans was given credibility by a reporter. I'm not including the Post reporter in that league, by any means. The Post story is a good one, on the whole.

But it still leaves me with a lot of questions, particularly given our recent brush-up with a shady RE broker who advocates that buyers talk desperate sellers into "assumptions" that work only if the lender is defrauded by not being informed. But is this scam really being directed at "desperate sellers"? Or is there some RE agent who owns a bunch of upside-down homes, who is trying to recruit "smart" buyers who will make payments on a stupid loan that isn't even in their name and let the upside-down owner "walk away" from the mess?

I'm asking you journalists who write about this stuff to keep digging, because the reality of the situation is that we're kind of past the historical moment for the kind of scam Gloria Ortiz got sucked into. The lenders are going bankrupt, and the ones left aren't making these loans any longer. But that means we are very, very much in the historical moment for massive seller fraud. There are way too many operators out there who own these upside-down properties, want out, and are looking for marks again.

Surely, many of the "desperate sellers" these days were themselves victims of fraud, and it's not inappropriate to have some sympathy for them. But all the stories I've been reading about "short sales" and "preforeclosure sales" and this "subject to sale" thing have simply assumed that the seller is the victim and that it's a good financial move for the buyer to take this "discounted" property. Well, I've got my doubts that whoever took the property from Hernandez in the Post story for $380,000 got a deal.

Nobody wants to have to report on "foreclosure avoidance scams" or "subject to" ripoffs after the fact, like we're only now reporting on predatory lending and predatory RE sales practices after the fact. Please, please. Let's get ahead of the curve on this one. Literally, we might prevent a few of them from happening, which is so much more satisfying than reporting on them after the fact.

There is predatory lending. There is predatory real estate selling. Let us not focus on the former to the exclusion of the latter.

Friday, March 21, 2008

Fed Denies Discussions to Buy MBS

by Calculated Risk on 3/21/2008 11:00:00 PM

Earlier I linked to the Financial Times story that suggested central banks were discussing buying mortgage back securities (MBS).

Greg Ip at the WSJ writes: Fed Says Not Discussing Coordinated MBS Buying

The U.S. Federal Reserve, responding to press reports, said it is not discussing coordinated purchases of mortgage-backed securities with other central banks.

"The Federal Reserve is not involved in discussions with foreign central banks for coordinated buying of MBS," a senior Fed official said.

Condo Woes

by Calculated Risk on 3/21/2008 08:11:00 PM

I've mentioned several times that many condos (especially high rise) are not included in the new home sales and inventory report from the Census Bureau. For those areas with a large number of high rise condos, the supply of housing units could be much higher than the Census Bureau statistics would indicate.

Jennifer Forsyth and Jonathan Karp discuss the condo supply problem in the WSJ: Woes in Condo Market Build As New Supply Floods Cities

More than 4,000 new units will be completed in both Atlanta and Phoenix by the end of the year. Developers in Miami and Fort Lauderdale, Fla., are readying nearly 10,000 total new units in a market already struggling with canyons of unsold condos. San Diego, another hard-hit region, will add 2,500 units, according to estimates provided by Reis Inc., a New York-based real-estate-research firm.If I'm reading this correctly, this is the delinquency rate for condominium construction and development (C&D) loans.

The new building comes on top of unprecedented supply.

...

Lenders of all sizes have $42 billion of condominium debt on their books, according to Foresight Analytics. In just three months -- between the third and fourth quarters of last year -- the delinquency rate rose to 10% from 5.9%, says the Oakland, Calif., research firm.

Central Banks Discuss Buying MBS

by Calculated Risk on 3/21/2008 07:13:00 PM

From the Financial Times: Central banks float rescue ideas

Central banks on both sides of the Atlantic are actively engaged in discussions about the feasibility of mass purchases of mortgage-backed securities as a possible solution to the credit crisis.To understand the economic arugment, see Professor DeLong's Post-Meltdown After-Action Report: The Housing Market, the Tasks of the Fed and the Treasury, and Economists' Reputational Bets (see diagrams about half way down post).

...

Any move to buy mortgage-backed securities would require government involvement because taxpayers would be assuming credit risk.

Petroleum Prices and GCC Spending

by Calculated Risk on 3/21/2008 01:17:00 PM

Note: this post is highly speculative and only a possibility that may be worth considering - something for a holiday. Best wishes to all.

Rachel Ziemba (filling in for Brad Setser) at RGE Monitor discusses how petrodollars are being spent by the GCC (Gulf Cooperation Council) countries in Petrodollars: How to Spend It

The following graph is interesting. This reminds me of how the surge in California state government revenues in the late '90s (due to the tech stock bubble), led to a concurrent surge in government spending. When the tech bubble burst, the state budget went bust.

The same pattern has been repeated across the U.S. recently with surging government spending based on revenues from the housing bubble. Now, almost every week, we see a story about some state or local government laying off workers and cutting their budget as revenues from housing decline.

So when I saw this graph, my first thought was: What happens if oil prices fall? Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

Rachel Ziemba writes:

2007 was the first year that spending growth outstripped revenues [growth] in the GCC and many other oil exporters. 2008 budget plans imply even higher current (especially wages and subsidies) and capital expenditures. Even countries that have traditionally saved more (Kuwait) are ramping up spending especially on capital projects and in some cases transfers to the population or pension funds. ... With megaprojects in the works in a variety of sectors including energy and other infrastructure, capital spending will likely continue to rise.Further Ziemba argues - based on spending growth - that "many GCC countries might have very small current account surpluses" within 5 year, if oil prices hold steady. It appears the GCC spending plans depend on fairly high oil revenues.

But could oil prices fall sharply?

Setting aside peak oil arguments for now, it's important to realize that both the supply and demand curves for oil are, in general, very steep. If there is little unused capacity, it takes time for more oil production to become available since this involves huge capital intensive projects. And, in the short term, demand is fairly inelastic over a wide range of prices; people stay with their routines and keep their same vehicle. With two steep curves (supply and demand), a small increase in quantity demanded will lead to a large increase in prices.

And, of course, the opposite is also true. A relatively small decrease in demand (or increase in supply) would cause a significant drop in price.

As the U.S. economy weakens, there is waning demand for oil in the U.S.:

According to the US Energy Information Administration's weekly inventory report, the overall consumption of oil and crude products dropped 3.2 percent in the last four weeks compared to the same period last year.Perhaps the growth in demand in China and India (and elsewhere) will more than offset the small decline in U.S. demand. But there may be another important factor - the behavior of the GCC countries.

What if the supply-demand curve for oil has multiple equilibrium points? And what if the GCC countries have been limiting production because of the lack of other investment opportunities? The following is from a paper by Professor Krugman several years ago: The Energy Crisis Revisited

The fact that oil is an exhaustible resource means that not extracting it is a form of investment. And it is an investment that might look attractive to a national government when oil prices are high. If a country does not want to spend all of the massive flow of cash generated by a sudden price increase on consumption, it must do one of three things: engage in real investment at home, which is subject to diminishing returns; invest abroad; or "invest" by cutting oil extraction, and hence reducing supply.

Krugman: Figure 1.

Krugman: Figure 1.So there is a definite possibility that over some range higher oil prices will lead to lower output. And given highly inelastic demand, as Cremer et al showed, that means that you can have multiple equilibria. Figure 1 illustrates the point: given the backward-bending supply curve and a steep demand curve, there are stable equilibria at both the low price PL and the high price PH.So there is a possibility that what has looked like peak oil to some observers (something I believe is coming), was actually GCC countries investing by not extracting oil. If oil prices start to fall, and with rising expenditures (see first graph again), the GCC countries might increase production - causing prices to fall further.

And falling oil prices would have a significant impact on the U.S. trade deficit:

This graph shows the total trade deficit (in blue) over the last 10 years. The red line is the trade deficit excluding petroleum products, and black is the petroleum deficit.

This graph shows the total trade deficit (in blue) over the last 10 years. The red line is the trade deficit excluding petroleum products, and black is the petroleum deficit. The ex-petroleum deficit is falling fairly rapidly, but the overall trade deficit is declining slowly, because of the surge in oil imports (in dollars, not quantity).

There are many potential impacts of falling oil prices - such as geopolitical issues with oil producing nations - but from a U.S. perspective this would help with the trade deficit, possibly the dollar, and cushion the impact of the current U.S. recession.

This is just something I've been musing about ... best to all.

The Cayne Mutiny and the Thornburg Carry

by Anonymous on 3/21/2008 08:17:00 AM

This, via Felix via Yves, is funny.

Floyd Norris ruminates on the the Bear business as well as the curious details of the Thornburg Mortgage deal:

The deal negotiated by Thornburg got the banks to promise there would be no more margin calls for a year, by which time, it is hoped, the securities would have regained value. The cost to Thornburg of getting that concession was to give warrants to the banks to buy a lot of stock at a penny a share, and to promise to raise at least $1 billion in cash within days. That cash would provide a margin of safety for the banks even if the mortgage securities market continues to decline.That negative carry trade thingy hurts.

To borrow that money, Thornburg is offering convertible bonds paying 12 percent annual interest. Add in some extra warrants, and buyers of the bonds will be able to get stock for less than 72 cents a share. If they convert, they will own 86 percent of the company, while the bankers will have an additional 3 percent — for which they will pay 1 cent a share. Existing shareholders will have an 11 percent stake.

If, that is, the bonds sell. On Thursday night, the bond offering was delayed until Monday, a sign that the underwriters may be having trouble rounding up buyers.

Logically, the shares should trade for 50 cents or less if these are the terms Thornburg must pay to borrow, but the price has stayed well above that level. So why did the shares not collapse?

Perhaps shareholders hope to vote the deal down, but that would remove only the conversion privilege from the bonds. Bondholders would still get warrants, and their interest rate would go up to 25 percent. It is hard to explain rationally, but perhaps some buyers heard the company had a plan to stay afloat, and ignored the details.

Thornburg officials would not talk to me, but it is not easy to understand how they expect to make this deal work for very long. Thornburg’s longtime strategy was to borrow at low rates to finance mortgage securities paying higher rates. Now it will pay 12 percent to help support securities paying a much lower rate of interest.

Thursday, March 20, 2008

Delinquencies Rise for Small Home Builders

by Calculated Risk on 3/20/2008 09:24:00 PM

Michael Corkery at the WSJ writes: Mortgage Mess Hits Home For Nation's Small Builders

This article discusses how small builders all across the country are falling behind on their Construction and Development loans (C&D) and some are filing bankruptcy. This is impacting local small banks too:

Builders' problems are now threatening losses for small and medium-size regional banks. Muscled out of the mortgage business by large national lenders, many of these banks flocked to construction lending as the housing market boomed ... they are the front-line casualties when builders and developers can't make their payments.

Click on image for WSJ graphic.

This graphic (at the WSJ) shows the stunning increase in 30 day past due rates on C&D loans between Q1 2007 and Q4 2007.

Also check out the graphic (see WSJ article) of the overall C&D 30 day past due rates over time. In mid-2006, only 1% of C&D loans were 30 days past due. In Q4, 2007, it was close to 8% (and rising rapidly).

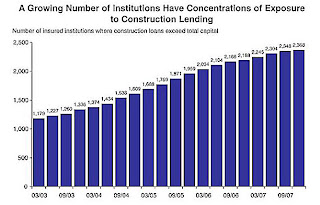

Many small and mid-size institutions have a high concentration of C&D loans. The following graph is from the FDIC's quarterly banking profile released in February:

"A Growing Number of Institutions Have Concentrations of Exposure to Construction Lending"

"A Growing Number of Institutions Have Concentrations of Exposure to Construction Lending"This graph shows the number of institutions, by quarter, where the construction loans exceed total capital.

These are the higher risk institutions. There are 2,368 institutions that met this criteria in Q4 2007, out of 8500 insured institutions.

And there is also the problem with Commercial Real Estate (CRE) loan concentrations ...

Mortgage Rates and the Ten Year Treasury

by Calculated Risk on 3/20/2008 04:44:00 PM

Thirty year mortgage rates fell sharply in the last week. Housing Wire reports the Bankrate.com numbers: Mortgage Rates Swoon Amid Market Uncertainty

Fixed mortgage rates fell sharply in the past week, with the average conforming 30-year fixed mortgage rate now 5.98 percent — a 41 basis-point drop from last week. According to Bankrate.com’s weekly national survey of large lenders, the average 30-year fixed mortgage has an average of 0.38 discount and origination points.And from Freddie Mac: Long-term mortgage rates plummet

Freddie Mac today released the results of its Primary Mortgage Market Survey® (PMMS®) in which the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage (FRM) averaged 5.87 percent with an average 0.5 point for the week ending March 20, 2008, down from last week when it averaged 6.13 percent.Freddie Mac reported mortgage rates were this low in the middle of February (about one month ago).

The following graph compares the weekly 30 year mortgage rate (as reported by Freddie Mac) with the weekly ten year treasury yield. The black line is the spread between the two rates.

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.The spread between the ten year treasury and the 30 year mortgage tends to rise when the ten year yield is falling sharply. This is probably because investors believe homeowners will hold their mortgages longer. This can be seen in 2002 and again last year.

However the recent increase in the spread is probably due more to liquidity issues, as opposed to an increase in holding period. Last week 30 year mortgage rates declined both because the ten year yield declined, and because the spread declined somewhat. Still, the spread of 2.5% for GSE loans above the ten year yield, is still 0.5% or more above the normal spread. The spread will probably decline further if the liquidity crisis eases.

Dow Jones Reports Home Builder Cancellation Rate Now 43%

by Calculated Risk on 3/20/2008 02:33:00 PM

Dow Jones reported today that the average home builder cancellation rate is currently 43%.

From Dow Jones: For Home Builders, Cancellations Create Expensive Problem (no link yet)

Many contracted buyers, spooked by falling home prices or suddenly unsure of their financial state, are fleeing before closing. The average cancellation rate now tops 43% - leaving builders saddled with even more unplanned, unsold and unwanted homes.Unfortunately the article doesn't provide the cancellation rate for previous periods, other than to state "the average cancellation rate dipped slightly in the fourth quarter".

The data I compile (probably a subset of the Dow Jones data) shows the cancellation rate dipped slightly to just below 40% in Q4, from a peak of 42.5% in Q3 2007.

Cancellations rates are important when following the reported new home sales and inventory from the Census Bureau. The Census Bureau doesn't include cancellations in their report.

The actual sales could be calculated as total houses sold minus cancellations in the month. The total houses sold would include new sales, plus sales of houses cancelled in previous periods.

We could write this as:

Total Sales = Sales(new) + Sales(Previous cancellations) - Cancellations

But the Census Bureau reports sales as Sales(new) only, and they ignore both factors of cancellations (if a house was sold previously, then cancelled, then resold, it isn't included in the sales numbers). This works fine as long as cancellation rates are fairly steady.

However, with rising cancellation rates, the Census Bureau overstates sales, and understates the increase in inventory (or overstates a decrease in inventory). For cancellation adjusted inventory, see my post: Housing Starts, New Home Sales and Cancellations

The opposite is also true: during periods of declining cancellations, the Census Bureau under reports sales, and overstates inventory. This will be very important in the coming year, since cancellation rates will likely decline as builders require larger deposits and take other steps to avoid cancellations.

ECRI: U.S. "unambiguously" in a recession

by Calculated Risk on 3/20/2008 12:43:00 PM

ECRI has finally called the recession.

From Reuters: Leading index shows US economy in recession, ECRI says

The United States is "unambiguously" in a recession ... citing a nine-month decline in its weekly measure of the economy.ECRI may have called the 2001 recession, but they are late to the party on this one.

The Economic Cycle Research Institute, which correctly predicted the 2001 recession at a time when many on Wall Street still maintained a rosy outlook, said their numbers indicate the economic contraction is already under way.

Extending its weakening trend, the firm's Weekly Leading Index fell to 130.8 in the week of March 14 from 132.1 in the prior week, revised down from 132.2.

"It is exhibiting a pronounced, pervasive and persistent decline that is unambiguously recessionary," said Lakshman Achuthan, managing director at ECRI.