by Calculated Risk on 12/29/2007 04:54:00 PM

Saturday, December 29, 2007

Looking back at 2007 Housing Predictions

At the end of 2006, I offered some predictions for housing in 2007. Looking back it's hard to believe these predictions were out of the mainstream.

My overall view for the 2007 housing market was "falling prices, falling sales, falling residential construction employment, falling starts, falling MEW, falling percentage of equity, and rising foreclosures".

I expected that "existing home sales will "surprise" to the downside, perhaps in the 5.6 to 5.8 million unit range". It now looks like existing home sales will be close to 5.6 million.

I expected prices to fall "1% to 3% nationwide" as measured by OFHEO. OFHEO reports that the Purchase Only index are up 1.1% for the first three quarters, with prices falling in Q3. It now looks like OFHEO prices will be about flat for the year. Another index, S&P / Case-Shiller, shows prices down 3.7% through the first three quarters of 2007.

I also argued "Foreclosures will be approaching record levels in some states." If anything, I was too optimistic on foreclosures. In California, Notice of Default activity is well above previous record levels.

And my biggest error was on residential construction employment. I argued:

"We will see record residential construction job losses in 2007.According to the BLS, residential construction employment has only fallen 222K in 2007. I've been showing this graph all year:

... the loss of 400K to 600K residential construction employment jobs over the next 6 months."

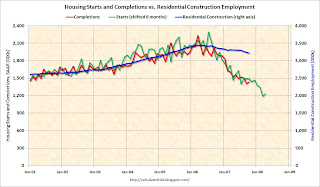

This graph shows starts, completions and residential construction employment. (starts are shifted 6 months into the future). Completions and residential construction employment were highly correlated, and Completions typically lag Starts by about 6 months.

This graph shows starts, completions and residential construction employment. (starts are shifted 6 months into the future). Completions and residential construction employment were highly correlated, and Completions typically lag Starts by about 6 months.There are many reasons why the BLS reported employment hasn't fallen as far as expected (blue line). Some of the possible explanations include: the BLS has not correctly accounted for illegal immigrants working in the construction industry, the BLS Birth/Death model might have missed the turning point in residential construction employment, many workers have moved to commercial work, and many workers (subcontractors) are underemployed.

There is some merit to to all of these arguments, and I think the answer will be some combination of these explanations. The concern now is that if commercial construction spending slows, as appears likely from the recent Fed loan survey, then workers that have moved to commercial construction will have no work opportunities.

This was the concern expressed by the director of forecasting of the NAHB in August. From Reuters: Construction job losses could top 1 million

"The ability of nonresidential to continue absorbing additional workers is going to be limited, and that's going to put downward pressure on construction employment overall," [Bernard Markstein, director of forecasting at the National Association of Home Builders] said, adding that cuts may be deeper than in the 1990s.Whatever the reason, I was too pessimistic on residential construction employment in 2007.

And finally, for amusement, Jon Lansner at the O.C. Register interviews local economist Mark Schniepp: Economist eyes home sales pickup in ‘08. This is an amazing quote:

A year ago, we didn’t know what a subprime loan was, nor did anyone expect the likelihood of a “credit crunch.”Oh yeah.

Economist Mark Schniepp, Dec 29, 2007

Tanta and I have been writing about subprime loans for as long as this blog has existed. And as far as a credit crunch, back in January I mentioned the possibility of "a credit crunch based on bad loans in the RE sector (and possibly in CRE and C&D too)".

And many others were discussing these issues too.

We all make errors in forecasting - no one has a crystal ball - but I'm endlessly amused by the 'no one could have known' excuse.

On Option ARMs

by Tanta on 12/29/2007 02:15:00 PM

This is a bonus post for those of you who use Excel (or some other software with which you can read and play with .xls files). I'm afraid that those of you who do not possess such software will have to use your imagination here. It's not especially practical to post images of big spreadsheets on the blog, so if you want to see the numbers, you'll need to download the spreadsheets.

These links will download the spreadsheets:

LIBOR-Indexed OA Projection

MTA-Indexed OA Projection

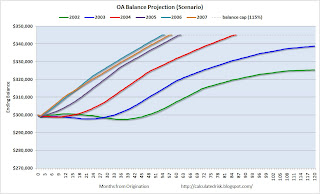

I made two of them for you to play with. Both show a to-date balance history, plus a future balance projection, for a hypothetical Option ARM with payments beginning in 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, or 2007. The loan terms are identical for each spreadsheet with the exception of the index chosen: one uses MTA, the other 1-Month LIBOR. The terms of these scenarios are in fact derived from real loan products out there, but of course there are other ways of structuring OAs. I am not making a claim about what product structure was most common (or most likely still to be on the books), as I don't have that kind of data.

What I had in mind for this exercise is to help people see, clearly, how these things work (some folks are still, Lord love you, a bit confused about OA mechanics. That undoubtedly includes some of you who have one. Remember that if you do, your loan might not work like this because the note you signed might have different terms regarding adjustment frequency, balance cap, margin, etc.) Besides that, I wanted to make a fairly simple point about the issue of resets, payment shock, and timing on these things.

That's why the spreadsheets show multiple vintages with identical loan terms: you can see that the actual speed of negative amortization and the forecast date of recast on these loans varies quite dramatically for the vintages, because of the huge impact of the very low 2002-2003 rate cycle. Each of these scenarios assumes that the borrower always makes the minimum payment from inception of the loan, and each assumes that future index values are identical to the most recent available index value (December 2007). Yet even in those circumstances, the earlier loans (2002 and 2003, especially) negatively amortize much more slowly than the later vintages.

My gifted co-blogger has actually created some lovely charts to help make that clear:  Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

If you've downloaded the spreadsheets, you can play around with them a little in terms of the future interest rates on these loans, and you can see how the recast date (the date the balance hits the balance cap and the loan payment must be recast to fully amortize over the remaining term) moves forward or back depending on what you do with the rates. This is one reason why modeling actual portfolios of OAs is such a challenge: you have to make assumptions about what will happen with the underlying index.

Of course, in actual portfolio modeling, you would also not assume that every borrower will always make the minimum payment. You would have to look at actual borrower performance to date, and calculate some "average" behavior or project each borrower's past behavior patterns into the future. I am not making the claim that all borrowers always make the minimum payment from inception; I'm trying to show what would happen, in some examples, if a borrower did that. I have heard estimates from different OA portfolios of anywhere from one-third to ninety percent of borrowers who have, historically, done that.

One other thing I wanted to make clear by providing these examples is the mechanics of payment increases for a very common OA type. The product shown in these spreadsheets allows for annual payment increases, but monthly rate increases. (That is how the potential for negative amortization gets created: the payment does not automatically adjust to match the new interest rate each month.) The eventual recast hits at the sooner of the loan reaching 115% of its original balance or 120 months. We know that a recast is nearly always a huge shock, given a low enough introductory rate. But this loan does involve payment increases of up to 7.5% each year (i.e., the next year's payment can be as much as 107.5% of the prior year's payment).

With the later vintage loans, especially, I for one have no confidence that the borrower was qualified at realistic enough original DTIs to withstand several years of payment increases, even before that nasty shock of the recast.

You may if you like change that introductory rate on these loans--I used 1.00%. You will see that increasing that introductory rate actually slows down the negative amortization in most scenarios. (That is because it creates a higher initial first year payment, which thus creates less of a shortfall between interest accrued and payment made.) I suspect that this fact about OA is surprising to some people, who think that folks who got a 1.00% "teaser" on these things got some real deal. In reality, a borrower who was given an introductory rate several points higher than that is probably doing much better, balance-wise.

My scenarios involve the assumption that the initial payment is fixed for only one year. There are OAs out there where the first payment change is two or even up to five years from the first payment date. (They will generally involve a higher introductory rate and margin.) You can change these spreadsheets to extend the original payment out for longer than a year, if you like, and you'll see just how much faster that balance cap hits when you extend the fixed payment period. Ouch.

Finally, while I chose the repayment periods I did quite arbitrarily, you will notice that for both the MTA and LIBOR scenarios, the most recent index value (December 2007) is substantially lower than it had been for quite some time. This means that my balance forecast here just happens to have picked up a relatively low last known index to project out into the future. Had we done this exercise several months ago, the projected future index value would have been higher, and hence the future negative amortization would have been faster. It's an issue to keep in mind as we look at portfolio and security projections regarding OA recasts; those will have to be updated from time to time as rate history unfolds.

And yes, there's a pig, if that makes you want to bother downloading the spreadsheets.

Friday, December 28, 2007

Fed gives Tanta a Hat Tip

by Calculated Risk on 12/28/2007 07:00:00 PM

From Adam Ashcraft and Til Schuermann: Understanding the Securitization of Subprime Mortgage Credit

See page 13:

Several point raised in this section were first raised in a 20 February 2007 post on the blog http://calculatedrisk.blogspot.com/ entitled “Mortgage Servicing for Ubernerds.”Note: there is link in the menu bar for Tanta's UberNerd series: The Compleat UberNerd.

Here is the introduction:

How does one securitize a pool of mortgages, especially subprime mortgages? What is the process from origination of the loan or mortgage to the selling of debt instruments backed by a pool of those mortgages? What problems creep up in this process, and what are the mechanisms in place to mitigate those problems? This paper seeks to answer all of these questions. Along the way we provide an overview of the market and some of the key players, and provide an extensive discussion of the important role played by the credit rating agencies.This report is recommended reading to understand the entire securitization process. Congratulations to Tanta, and hopefully she will comment on the report.

In Section 2, we provide a broad description of the securitization process and pay special attention to seven key frictions that need to be resolved. Several of these frictions involve moral hazard, adverse selection and principal-agent problems. We show how each of these frictions is worked out, though as evidenced by the recent problems in the subprime mortgage market, some of those solutions are imperfect. In Section 3, we provide an overview of subprime mortgage credit; our focus here is on the subprime borrower and the subprime loan. We offer, as an example a pool of subprime mortgages New Century securitized in June 2006. We discuss how predatory lending and predatory borrowing (i.e. mortgage fraud) fit into the picture. Moreover, we examine subprime loan performance within this pool and the industry, speculate on the impact of payment reset, and explore the ABX and the role it plays. In Section 4, we examine subprime mortgage-backed securities, discuss the key structural features of a typical securitization, and, once again illustrate how this works with reference to the New Century securitization. We finish with an examination of the credit rating and rating monitoring process in Section 5. Along the way we reflect on differences between corporate and structured credit ratings, the potential for pro-cyclical credit enhancement to amplify the housing cycle, and document the performance of subprime ratings. Finally, in Section 6, we review the extent to which investors rely upon on credit rating agencies views, and take as a typical example of an investor: the Ohio Police & Fire Pension Fund.

We reiterate that the views presented here are our own and not those of the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. And, while the paper focuses on subprime mortgage credit, note that there is little qualitative difference between the securitization and ratings process for Alt-A and home equity loans. Clearly, recent problems in mortgage markets are not confined to the subprime sector.

Also note the last two sentences of the introduction: "... while the paper focuses on subprime mortgage credit, note that there is little qualitative difference between the securitization and ratings process for Alt-A and home equity loans ... recent problems in mortgage markets are not confined to the subprime sector."

Legg Mason Bails Out Cash Funds

by Calculated Risk on 12/28/2007 06:57:00 PM

From Bloomberg: Legg Mason Shores Up Cash Funds With $1.12 Billion

Legg Mason Inc. pumped $1.12 billion into two non-U.S. cash funds to prevent losses, the biggest bailout by a money manager tied to asset-backed debt sold by structured investment vehicles.The Confessional is still open.

The move, along with an earlier cash infusion, will reduce earnings per share by 15 cents in the quarter ending Dec. 31, the Baltimore-based company said today in a statement.

$1 Trillion in Mortgage Losses?

by Calculated Risk on 12/28/2007 03:40:00 PM

Update: added comments from Tanta at bottom.

Several recent articles have referenced my post on the possibility of a change in attitude towards foreclosure. I wrote:

One of the greatest fears for lenders (and investors in mortgage backed securities) is that it will become socially acceptable for upside down middle class Americans to walk away from their homes.Although the purpose of the post was to discuss changing social norms, the primary reason the post was mentioned was because of some pretty big numbers, like the possibility of $1 trillion in mortgage losses based on a few rough assumptions. A couple of quotes:

Australia theage.com: Americans 'walk' from loans

Late last week ... Calculated Risk figured that housing losses might reach $US1 trillion and even $US2 trillion.WSJ: How High Will Subprime Losses Go?

Back in the U.S., the Calculated Risk blog sidestepped the colorful language and went straight for the big number: “The losses for the lenders and investors might well be over $1 trillion.”The $1 trillion number is a simple calculation: If prices fall 30%, then approximately 20 million U.S. homeowners will be upside down on their mortgages. If half of these homeowners walk away from their homes, with an average 50% loss to lenders and investors, that is $1 trillion in losses (the average mortgage is just over $200K).

This wasn't a forecast, just a simple exercise to show why changing social norms is very scary for the lenders.

And this isn't just a subprime problem, and these aren't just potential "subprime losses". In the original post I referred to the potential of foreclosures becoming "socially acceptable" for the middle class.

But even though the problems have spread far beyond suprime, some reporters are stuck on the subprime meme. As an example, Bloomberg columnist John M. Berry wrote: Subprime Losses Are Big, Exaggerated by Some

As the U.S. savings and loan crisis worsened in the 1980s, analysts tried to top each other's estimates of the debacle's cost to the federal government.This is subprime reporting. It's absurd to think that mortgage losses will only come from subprime loans; in fact most of the upside down homeowners will be Alt-A and prime borrowers. By focusing solely on subprime, Berry misses the larger mortgage problem.

Much the same thing is happening now with losses linked to subprime mortgages, with figures of $300 billion to $400 billion being bandied about.

A more realistic amount is probably half or less than those exaggerated projections -- say $150 billion. That's hardly chicken feed, though not nearly enough to sink the U.S. economy.

A loss of $150 billion would be less than 12 percent of the approximately $1.3 trillion in subprime mortgages outstanding. About $800 billion of those are adjustable-rate mortgages, the remainder fixed rate.

And the credit problems extend well beyond mortgages. As an example, from Bloomberg this morning: Citigroup, Goldman Cut LBO Backlog With 10% Discounts

Citigroup Inc., Goldman Sachs Group Inc., Morgan Stanley and JPMorgan Chase & Co. are offering discounts of as much as 10 cents on the dollar to clear a $231 billion backlog of high-yield bonds and loans.We don't know the exact haircut on each LBO deal, but an average 5% haircut would be over $10 billion in losses. And there are losses coming from corporate debt, CRE loans, and other consumer debt too. As Floyd Norris asked at the NY Times this morning: Credit Crisis? Just Wait for a Replay

"... just how different was subprime lending from other lending in the days of easy money that prevailed until this summer?"Short answer: not very.

Back to mortgage losses, both Felix Salmon: Are Subprime Losses Being Exaggerated? and Paul Krugman, Jingle mail, jingle mail, jingle mail — eek! bring up a key issue: recourse vs. non-recourse loans. Felix writes:

... no one is going to have a real handle on mortgage losses unless and until someone manages to get a handle on the percentage of mortgage loans which are non-recourse. If your house falls in value and you have a non-recourse mortgage, then it makes perfect economic sense for someone in a negative-equity situation to simply walk away – something known as "jingle mail". But given the amount of refinancing going on during the last few years of the mortgage boom, I suspect that the vast majority of mortgages are not non-recourse. (Refis are never non-recourse.)This is an important issue. In California, purchase money is non-recourse. If the borrower walks away and mails in the keys (Fleckenstein's "jingle mail"), the lender is stuck with the collateral. However, if the California borrower refinanced, then the lender has recourse, and can pursue a judicial foreclosure (as opposed to a trustee's sale), and seek a deficiency judgment.

The lender can enforce that deficiency judgment by attaching other assets, or by garnishing the borrower's wages. Historically lenders rarely pursued (or enforced) deficiency judgments, but that could change if many middle class borrowers, with solid jobs and assets, resort to jingle mail.

For purchase money, state law determines the recourse vs. non-recourse issue. As Felix noted, refis are always recourse, and there was significant refi activity in recent years.

But before we think most loans are recourse, we have to remember that about 22.3 million homes were purchased during the last 3 years (2005 through 2007), and in a period of rising rates, many of these homeowners probably did not refi. It's difficult to estimate the exact losses - since we don't know the percent of recourse loans, we don't know how far prices will fall, and we don't know how homeowners will react to being upside down - but we know the losses will be significant.

Note: I'm trying to find a state by state list of recourse vs. non-recourse for purchase money.

On recourse loans, Tanta adds (via email):

I suspect that you will have some very aggressive lenders and some not very aggressive lenders in that respect.

Which will tell you who thinks it doesn't have a fraud problem and who does.

Back in my day working for a servicer, we never went after a borrower unless we thought the borrower defrauded us, willfully junked the property, or something like that. If it was just a nasty RE downturn, it rarely even made economic sense to do judicial FCs just to get a judgment the borrower was unlikely to able to pay. You could save so much time and money doing a non-judicial FC (if the state allowed it) that it was worth skipping the deficiency. Plus we had a soft spot, I guess.

At any rate, the absolute all time last possible thing you could get me to do is send an attorney barging into court demanding a deficiency judgment if I had any reason whatsoever to fear that my own effing loan officer was implicated in fraud on the original loan application. Any borrower with half a brain will raise that as a defense, and any judge even slightly awake will not only deny the deficiency but probably make the lender pay all costs, or worse. And I'd call that justice.

This goes double if the loan was made as a "stated asset" deal. I can just hear a judge asking me why I deserve to get other assets now when I never bothered to make sure the borrower had any in the beginning.

So yes, some people will get hit with a deficiency. But I'm not sure it will be as many as you might think. T

Thornberg: Housing prices are headed way down

by Calculated Risk on 12/28/2007 01:57:00 PM

Dr. Christopher Thornberg writes in the LA Times: Realty reality: Housing prices are headed way down

In 2002, the median price of a single-family home in Los Angeles was $270,000 and the median homeowner's income was $65,000. With a $50,000 down payment, the annual cost of that house (taxes, insurance and payment on a 30-year fixed-rate conventional mortgage) would add up to about 33% of the median household's income -- just under the 35% mark that the Federal Housing Administration calls the upper limit of "affordable."I believe Thornberg's price forecast is for Los Angeles. It appears his "everywhere" comment is referring to all the neighborhoods in LA.

By 2006, the cost of that same house doubled, to $540,000 -- pushed by unbridled speculation fueled by unparalleled access to mortgage capital. But median income rose a paltry 15%. So today that same set of costs come to 60% of gross income.

... Prices must and will fall. Everywhere. Probably 25% to 30% from their peak.

More on New Home Sales

by Calculated Risk on 12/28/2007 11:01:00 AM

First, a couple of key points to consider on housing.

Note: For more graphs, please see my earlier post: November New Home Sales

Let's start with revisions. This month (November) is one of the few months were the initial report wasn't higher than the previous month. Usually the small reported gain in sales is then revised away in subsequent releases.

Look at the report today (for November), the Census Bureau revised down sales for August, September and October. This has been the pattern for most of the housing bust; almost all the revisions have been down. I believe the Census Bureau is doing a good job, but the users of the data need to understand what is happening (during down trends, the Census Bureau initially overestimates sales).

For an analysis on Census Bureau revisions, see the bottom of this post.

Next up, inventory. The Census Bureau reported that inventory was 505 thousand units. But this excludes the impact of cancellations. Currently the inventory of new homes is understated by about 100K (See this post for an analysis of the impact of cancellations on inventory).

This also means that the months of supply is understated. The Census Bureau reported the months of supply as 9.3 months. After adjusting for the impact of cancellations, the actual months of supply is probably closer to 11.3 months. Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

This graph shows New Home Sales vs. Recession for the last 35 years. New Home sales were falling prior to every recession, with the exception of the business investment led recession of 2001.

This is what we call Cliff Diving!

And this shows why so many economists are concerned about a possible consumer led recession - possibly starting right now.

The second graph compares annual New Home Sales vs. Not Seasonally Adjusted (NSA) New Home Sales through November.

Typically, for an average year, about 93% of all new home sales happen before the end of November. Therefore the scale on the right is set to 93% of the left scale.

Through November, there have been 732 thousand New Home sales, and, with one month to go (and a few revisions) it looks like New Home sales for 2007 will be around 775 thousand - the lowest level since 1996 (758K in '96).

November New Home Sales

by Calculated Risk on 12/28/2007 10:00:00 AM

According to the Census Bureau report, New Home Sales in November were at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 647 thousand. Sales for October were revised down to 711 thousand, from 728 thousand. Numbers for August and September were also revised down.

This is another VERY weak report for New Home sales. All revisions continue to be down. This is the fourth report after the start of the credit turmoil, and, as expected, the sales numbers are very poor.

I expect these numbers to be revised down too. More later today on New Home Sales.

Option ARM Tightening

by Tanta on 12/28/2007 08:45:00 AM

A quite decent piece on Option ARMs in the LA Times. I liked this part:

Despite such risks, the initial low payments on option ARMs have kept a lid on serious delinquencies -- 3.7% of all option ARMs, Standard & Poor's analysts said in a report last week. That's higher than before, but still low compared with the 6.3% delinquency rate on loans to good-credit borrowers with so-called hybrid ARMs, which have a low fixed rate for two to 10 years before becoming adjustable-rate loans.I made an argument a while ago that focussing regulator attention exclusively on disclosure documents can be just a touch beside the point if lenders are no longer offering the product in question. You have to wonder, if we just cut off 80-90% of the OA borrower pool, whether the remaining 10% really need those new and improved disclosures, or can muddle along with the ones already in use. If you take the OA out of the mass market and put it back into the high-net worth, high-income crowd it was originally designed for, you might find that your borrowers are already selected to be people who either read and understand disclosures, or who hire an attorney or financial planner to read them. I can certainly think of better uses for regulators' time and energy than fooling around with disclosure documents that would be clear to borrowers who are now in a rather different kind of trouble than not understanding the teaser rate on their OA.

At Calabasas-based Countrywide Financial Corp., which S&P said made about a quarter of all option ARMs last year, 3% of such loans held by the lender as investments were delinquent at least 90 days, up tenfold from 0.3% a year earlier. Delinquency rates were even higher on option ARMs from other lenders, including Pasadena-based IndyMac Bancorp and Seattle's Washington Mutual Inc., S&P said.

Countrywide and other lenders tightened their lending standards last summer to ensure borrowers could afford loans after the interest rates adjusted upward.

Had those guidelines been in effect previously, Countrywide recently said, it would have rejected 89% of the option ARM loans it made in 2006, amounting to $64 billion, and $74 billion, or 83%, of those it made in 2005.

The other thing to notice is that the obligatory example borrower supplied in the article is having trouble with her first payment increase (the typical 7.5% annual increase in the minimum payment), which is still not enough to cover all the interest due. As that sort of situation increases (as more and more 2005-2006 vintage OAs get to their second or third payment increase), we'll start seeing defaults long before the recast date.

Speaking of which, when I am not making cartoon pigs I have been creating some spreadsheets to show examples of how to project the recast date on Option ARMs. That's total and compleat Nerd territory, but if anyone is interested I'll post them (as spreadsheets or as images thereof). You tell me whether that's more detail than you can stand or not.

Welcome to Our World

by Tanta on 12/28/2007 08:14:00 AM

Floyd Norris, New York Times, December 28, 2007:

Gee Willikers. If it's not just subprime, there might be enough material in it to, oh, fill a whole blog. Or several dozen of them.What if it’s not just subprime?