by Calculated Risk on 9/30/2007 04:46:00 PM

Sunday, September 30, 2007

WSJ: UBS Is Expected to Report Loss

From the WSJ: UBS Is Expected to Report Large Loss From Fixed-Income Unit

...UBS ... is projecting a third-quarter loss of ... ($510 million to $600 million) based on a writedown of 3 billion to 4 billion Swiss francs for fixed-income assets ...The confessional is now open.

...

Its losses resulted from applying sharply lower market values to asset-backed bonds ... Many banks had serious troubles with securities-tied to mortgages when liquidity dried up in the last quarter.

Morgenson Watch

by Tanta on 9/30/2007 11:50:00 AM

I don't know how many posts I've written on Gretchen Morgenson's terrible reporting. I guess I'm going to have to start keeping score. "Can These Mortgages Be Saved?" Can this "reporter" be saved?

Her latest attempt to go after Countrywide, for sins real and imagined, contains the following "reportage":

But on the billions of dollars worth of mortgage loans that have been sold to investors in the last few years, it is not the banks or lenders like Countrywide that are hit with big losses when homes go into foreclosure. It is the sea of faceless investors who own pieces of these trusts. Also, under the trusts’ pooling and servicing agreements, Countrywide and other servicers typically recoup any costs they cover in the foreclosure process, such as legal and appraisal fees.I cannnot, literally, think of a better way to stir up sympathy for Countrywide than printing crap like this.

Borrower advocates fear that fees imposed during periods of delinquency and even foreclosure can offset losses that lenders and servicers incur. Few borrowers know, for example, that when they make only partial payments on their mortgages, servicers do not credit those payments against the principal or interest on their loan. Instead, the partial payments are deposited into a so-called suspense account. Servicers can dip into these funds and make use of them as interest-free loans, although the funds have to be accessible when the borrower becomes current on payments. In the meantime, borrowers — whether or not they know it — are still zapped with fees and charges for delinquent mortgage payments.

“The foreclosure process is a profit opportunity for servicers and lenders, but there is very little oversight of the fees imposed,” said Michael D. Calhoun, president of the Center for Responsible Lending. “There are a lot of folks trying to squeeze distressed borrowers.”

1. Servicers recoup foreclosure expenses because servicers are servicers. Investors are investors. Investors buy the credit risk; they therefore cover foreclosure costs. This is a perfectly normal arrangement. If you think there's a problem with it, can you explain how being reimbursed for an out-of-pocket expense, like a fee paid to a lawyer or an appraiser, is "making a profit"? Are you saying there's a markup in there? Do you have evidence for that?

2. Servicers are not now and have never been required to accept partial payments. Mortgage loans are not free-form Option ARMs where the borrower gets to decide how much principal or interest to pay this month; all of them, even the real OAs, have "minimum payments." If a distressed borrower talks a servicer into accepting a period of partial payments, to be made up later, that is called a payment plan or forbearance arrangement or some other "workout," and it takes the servicer's consent.

3. Putting partial payments in "suspense" means they don't get posted to the customer's account. It does not mean that the money goes into the servicer's own account. Those funds go into custodial accounts to which servicers cannot "dip in." Servicers do receive float income on those accounts, but of course in most cases they are also obligated to advance the full payment to the investor, out of their own funds, until it is collected from the borrower. So advances do offset the float. This entire paragraph is such an egregious mismash that it's unbelievable.

4. Foreclosure is a profit opportunity? What does that mean? That mortgage loan servicing--which unfortunately does include having to foreclose loans when they default--is a profitable business? Well, yes. That's why people engage in it. Is the claim here that an unfair or excessive profit is being made off of foreclosures (but not off of performing loan servicing)? How? Specifically? The "examples" in these three paragraphs don't make any sense.

And I cannot begin to make sense of the "Connor" loan example. With the hashed-up timeline and limited information given it's impossible to figure out. All I can say is bang-up job of reporting.

Ms. Morgenson, if you want to keep up on your mission to portray Countrywide in the worst possible light, you are going to have to get an education from a reliable source at some point about how the mortgage industry works.

Saturday, September 29, 2007

What's Really Wrong With Stated Income

by Tanta on 9/29/2007 06:10:00 PM

I had pretty much decided that I had said all I have to say about stated income loans with this post, but now that, per Chevy Chase, IT'S BACK!, I'm going to say one more thing. Then I'm done.

Apologists for stated income always bring us back to this so-called "classic" loan involving a self-employed borrower who "needs" a stated income loan because income is hard to verify or, you know, the tax returns don't "show the whole picture." This is never, really, actually, an argument about why stating rather than verifying income is necessary, although it pretends to be. It's really about why people with volatile income or a preference for not paying taxes on their income should get the "benefit" of financing on the same terms as wage-slaves and people who don't cheat on their taxes. That argument will end just before the sun freezes, so I'm not at all interested in participating in it.

My big problem with stated income lending has never really been about the wisdom or importance or lack thereof of making mortgage loans to the self-employed. My problem has to do with elemental safety and soundness of lenders, in a way that may not be obvious, so I'm going to hammer it for a bit.

Let us take the "classic" stated income hypothetical loan: the borrower is self-employed, has been for years and years, is buying a house, and has some trouble verifying income. Imagine that everything else about the loan is just groovy: high FICO, big down payment, lots of cash reserves after closing, scout badges out the wazoo. I'm not "stacking the deck" here. This looks like a super loan in all respects, except that question about whether there is sufficient current income to service the borrower's debts, or reason to believe that current income will last long enough to get past payment three or so.

We can make this loan in one of two ways:

1. We go "stated income." The borrower provides no tax returns, and just happens to state income sufficient to produce a debt-to-income ratio of 36%, which just so happens to be the maximum traditional cut-off for "acceptable risk."

2. We go "full doc," and the underwriter does a complete income analysis. In writing, on the sacred 1008 (the Underwriting Transmittal in the file), the underwriter fully discusses the business and its cash flow, noting that a 24-month averaging of income is producing a DTI of 68%. However, the underwriter believes that cash flow trend is positive, that there are documented reasons to believe it will continue, that the borrower has sufficient personal cash assets not needed for the business to supplement income for debt service, and hence this high DTI is justified. The 1008 of course is countersigned by a senior credit officer, because it is an exception to normal lending rules--the DTI is too high--and also because we are doing our required Fair Lending monitoring, making sure that the exceptions we make are made fairly, not just to rich white folks or folks in certain zip codes, but to anyone who qualifies for them.

Either way, it's the same loan, but Number 1 was more "efficient." Same risk, right?

Wrong. The default risk of the individual loan is only one risk. There's another huge looming risk created in Number 1 that we keep ignoring.

What happens if the loan performs just fine for a while? Well, if it's held by a financial institution, that institution will be subject to periodic safety and soundness and regulatory compliance examinations. One major point of those exams is to make sure the institution is holding sufficient reserves and capital against its loan portfolio. Among other things, an examiner might look at some reports of loan activity. And on reports, Number 1 looks like a low-risk loan with a 36% DTI. Number 2 catches someone's attention.

But, you say, wouldn't an examiner's attention be caught by the fact that Number 1's "doc type code" is stated, making it the kind of apparent higher risk worth a look at the loan file? Well, not if we started this whole thing by having assumed that there's no additional risk in stated income if other loan characteristics are good enough. The whole circular argument--stated is OK for OK loans--means that this will be considered one of those "not high risk" stated income loans, because all the other data points (FICO, DTI, LTV, etc.) look good.

The odds, therefore, that Number 2 would get further review are high, because it stands out as an exception loan with a high DTI. The odds that Number 1 would get further review are no better or worse than random.

And for any other purpose, such as counterparty due diligence, investor approval, um, servicer ratings, etc., that relies on aggregated data, Number 1 isn't going to make the institution's average DTI look worse, while Number 2 will. It matters if you write enough of those loans.

And what does the institution risk by having an auditor or examiner take a look at the file for Number 2? Why, the risk is that the auditor or examiner will not agree with that analysis, or will find the documentation unconvincing, or will be troubled by an apparent over-willingness to make exceptions or something. This is how the game is played: the loan shows up on some examination problem report, management is forced to respond with a memo defending its underwriting practices, and possibly even more loans get reviewed as the examiners seek potential evidence that whatever they don't like about that file is part of a pattern. Any stray skeletons you might have in your loan file closet (and everyone has a few loans they rather wish they hadn't made, or had handled better when they made them) get dragged out onto the conference room table.

Number 1, in other words, doesn't attract scrutiny. And what happens if it actually goes bad?

Well, with Number 1, it's "clearly" the borrower's fault. He or she lied, and we can pursue a deficiency judgment or other measures with a clear conscience, because we were defrauded here. We can show the examiners and auditors how it's just not our fault. The big bonus, if it's a brokered or correspondent loan, is that we can put it back to someone else, even if we actually made the underwriting determination. No rep and warranty relief from fraud, you know.

With Number 2? There is no way the lender can say it did not know the loan carried higher risk. Of course, higher-risk loans do fail from time to time, and no one has to engage in excessive brow-beating over it, if you believed that what you did when you originally made the loan was legit. If you're thinking better of it now, at least with Number 2 you have an opportunity to see where your underwriting practice or assumptions about small business analysis went wrong.

For anyone using loan servicing databases to research risk factors, of course, Number 1 might cause the conclusion to be drawn that stated income is a risk independent of other loan features. Number 2 might cause the conclusion to be drawn that 68% DTIs just don't work out well on the whole. You could, of course, go back and update the system with Number 1, after it fails and your QC people get around to finding the true income numbers, so that the database will show the true ratio of 68%, but that gets you to the catching-examiner-attention problem above.

And what about Fair Lending compliance? Insofar as a lot of stated income lending is just a way around having to make a formal exception to your lending policies, it's a good way of hiding certain patterns in terms of who you let get away with what. We do ourselves no good by thinking that the current environment--in which any marginal risk can get a stated loan--is the permanent environment. Structural ways to avoid showing your exception patterns invite abuse.

I have said before that stated income is a way of letting borrowers be underwriters, instead of making lenders be underwriters. When I say make lenders be lenders, I don't mean let's not regulate them. I have no problem with regulatory examinations; far from it. I am someone whose signature (usually, in fact, as that second sign-off) has appeared on exactly these kinds of loans, and whose butt has been on the line for them. We all face having loans we approved go bad; the world works that way. What the stated income lenders are doing is getting themselves off the hook by encouraging borrowers to make misrepresentations. That is, they're taking risky loans, but instead of doing so with eyes open and docs on the table, they're putting their customers at risk of prosecution while producing aggregate data that appears to show that there is minimal risk in what they're doing. This practice is not only unsafe and unsound, it's contemptible.

We use the term "bagholder" all the time, and it seems to me we've forgotten where that metaphor comes from. It didn't used to be considered acceptable to find some naive rube you could manipulate into holding the bag when the cops showed up, while the seasoned robbers scarpered. I'm really amazed by all these self-employed folks who keep popping up in our comments to defend stated income lending. It is a way for you to get a loan on terms that mean you potentially face prosecution if something goes wrong. Your enthusiasm for taking this risk is making a lot of marginal lenders happy, because you're helping them hide the true risk in their loan portfolios from auditors, examiners, and counterparties. You aren't getting those stated income loans because lenders like to do business with entrepreneurs, "the backbone of America." You're not getting an "exception" from a lender who puts it in writing and takes the responsibility for its own decision. You're getting stated income loans because you're willing to be the bagholder.

And no, this doesn't particularly do much for my assessment of your business acumen. Frankly, I'd rather see your tax returns and your P&L and hear your story about how investments in the business you have made, with the intent to grow it wisely, have limited your income or made it highly variable, than to see you volunteer to risk prosecution for fraud because, you know, you really need to buy a house. Do you do business with people like that all the time? Are you typically attracted to deals that are claimed to be perfectly legitimate, except that it's important not to fully disclose certain facts to certain parties? Does that maybe explain some of your accounts receivable problems and your pathetic cash flow? It certainly seems to be explaining some lenders' cash-flow problems at the moment.

This isn't just an issue for regulated depositories. All those claims by securities issuers and raters about how we had no idea that gambling was going on in this joint are directly comparable. The tough news for the self-employed "respectable" borrower is that I don't care if you're individually willing to play bagholder: you can't afford to underwrite that collective risk. We have a major credit crisis that's proving that.

Saturday Rock Blogging

by Tanta on 9/29/2007 07:58:00 AM

Because Nehemiah was a bullfrog, but it croaked! Wake up from the AmeriDream! Help us celebrate the Death of the the DAP by liberating your inner 70s dork. Don't go telling me you read an economics and finance blog on Saturday morning but you're too cool for this number--I think I see a few of you in the audience shots.

FHA to Ban DAPs

by Calculated Risk on 9/29/2007 02:34:00 AM

From the WaPo: FHA Down Payment Rule To Ban Seller Financing

The Federal Housing Administration will prohibit borrowers from using seller-financed down payment assistance programs that have helped hundreds of thousands of people buy homes but have come under the scrutiny of federal authorities.One of my earliest posts on this blog concerned credit quality and blasted DAPs. I wrote:

Such programs allow home sellers to give money to charities, which in turn assist buyers with their down payments. The sellers pay the charities a service fee, but often recoup the money by charging a higher price for the homes, usually 2 or 3 percent more, or an amount equal to the down payment, according to a 2005 study by the Government Accountability Office.

In a conference call with reporters, Federal Housing Commissioner Brian Montgomery said the FHA will publish its new rule in the Federal Register on Monday. The rule, which is little changed from a preliminary version put out for comment in May, will go into effect 30 days after publication.

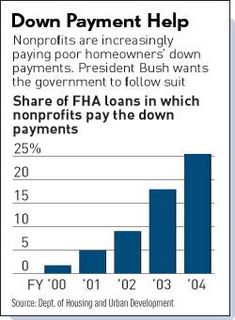

FHA loans are about 10% of all mortgages. They offer a 3% down payment loan - and that is still too much. So non-profit organization step in and pay the downpayment ... OK, actually the seller donates the downpayment to the non-profit and the non-profit gives it to the buyer. Amazing. DAPs were essentially non-existent 4 years ago and now make up 25% of FHA loans! See this chart:Since that chart was published the percentage of FHA loans using DAPs has increased according to the WaPo:

"... seller-financed down payment assistance has accounted for 30 to 50 percent of FHA purchase loans in recent years."And it was over a year ago that the IRS called DAPs a 'scam'. From the WaPo in June, 2006: IRS Ruling Imperils 'Gift Fund' Charities For Home Buyers

A ruling by the Internal Revenue Service threatens to extinguish a fast-growing -- but controversial -- charitable industry that has funneled hundreds of millions of dollars in cash to first-time home buyers for their down payments.It is stunning that it has taken this long to ban this practice. I'm also amazed that the MBA would oppose this ruling:

...

The IRS called the programs "scams" in its ruling last month and said that by providing down payments, the charities actually inflated home prices, making it more likely that homeowners would default on their loans.

The Mortgage Bankers Association ... blasted the ruling. The programs provide "important assistance to cash-strapped borrowers," said Steve O'Connor, the association's senior vice president of public policy.Nonsense.

Friday, September 28, 2007

From the Department of Credit Tightening

by Tanta on 9/28/2007 06:35:00 PM

FDIC: Netbank Fails

by Calculated Risk on 9/28/2007 04:58:00 PM

From the FDIC: FDIC Approves The Assumption of The Insured Deposits of Netbank, Alpharetta, Georgia (hat tip Red Pill)

On September 28, 2007, NetBank, Alpharetta, Georgia was closed by the Office of Thrift Supervision and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) was named Receiver. No advance notice is given to the public when a financial institution is closed.

...

NetBank, with $2.5 billion in total assets and $2.3 billion in total deposits as of June 30 ...

Estimating PCE Growth for Q3

by Calculated Risk on 9/28/2007 12:54:00 PM

The BEA releases Personal Consumption Expenditures monthly (as part of the Personal Income and Outlays report) and quarterly, as part of the GDP report (also released separately quarterly).

You can use the monthly series to exactly calculate the quarterly change in PCE. The quarterly change is not calculated as the change from the last month of one quarter to the last month of the next (several people have asked me about this). Instead, you have to average all three months of a quarter, and then take the change from the average of the three months of the preceding quarter.

So, for Q3, you would average PCE for July, August and September, then divide by the average for April, May and June. Of course you need to take this to the fourth power (for the annual rate) and subtract one.

The September data isn't released until after the advance Q2 GDP report. But we can use the change from April to July, and the change from May to August (the Two Month Estimate) to approximate PCE growth for Q3. Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

This graph shows the two month estimate versus the actual change in real PCE. The correlation is high (0.92).

The two month estimate suggests real PCE growth in Q2 will be about 3.0%.

In general the two month estimate is pretty accurate. Sometimes the growth rate for the third month of a quarter is substantially stronger or weaker than the first two months. As an example, in Q3 2005, PCE growth was strong for the first two months, but slumped in September because of hurricane Katrina. So the two month estimate was too high.

And the following quarter (Q4 2005), the two month estimate was too low. The first two months of Q4 were negatively impacted by the hurricanes, but real PCE growth in December was strong.

You can see a similar pattern in Q3 2001 because of 9/11.

Usually I go with the two month estimate (around 3%), however I think Q3 2007 might be one of the exceptions and real PCE growth could have slowed sharply in September (although maybe not until in October).

Housing: Starts, Sales and Forecasts

by Calculated Risk on 9/28/2007 12:00:00 PM

Hopefully this post will clear up some of the confusion regarding various housing statistics and forecasts. Take a look at the recent Goldman Sachs housing forecast - several people have asked if the numbers are consistent - can the excess inventory be worked off with New Home sales falling to 650K and starts "only" falling to 1.1 million units?

Here is a key point: New Home sales come from a subset of housing starts. Housing starts also include owner built units, rental apartments, and other units that would still not be included, if sold, in the New Home sales report. Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

This graph shows total housing starts and new home sales for the last 30 years. Although there are timing problems comparing starts to sales, these are the two most mentioned housing statistics, and this graph clearly illustrates the key point above.

Perhaps it would be helpful to divide starts into two major categories: Starts for homes that will be included in New Home sales, and All Other Starts. Unfortunately the Census Bureau doesn't provide this exact breakdown. But we can estimate "All Other Starts" from the above graph: the median for the last 30 years was 750K, and the minimum was 505K (during the recession of '91).

So, ceteris paribus, if New Home sales fall to 650K, we would expect total starts to fall to 1.4 million units (650K + 750K).

Of course all else isn't equal these days in the housing market - the outlook is especially grim - but perhaps not as grim as some forecasts. I'll post more on this topic this weekend.

August Construction Spending

by Calculated Risk on 9/28/2007 10:15:00 AM

From the Census Bureau: August 2007 Construction Spending at $1,166.7 Billion Annual Rate

The U.S. Census Bureau of the Department of Commerce announced today that construction spending during August 2007 was estimated at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of $1,166.7 billion, 0.2 percent above the revised July estimate of $1,164.4 billion. The August figure is 1.7 percent below the August 2006 estimate of $1,186.3 billion.

During the first 8 months of this year, construction spending amounted to $768.0 billion, 3.3 percent below the $794.0 billion for the same period in 2006.

...

[Private] Residential construction was at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of $522.1 billion in August, 1.5 percent below the revised July estimate of $529.8 billion.

[Private] Nonresidential construction was at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of $353.4 billion in August, 2.3 percent above the revised July estimate of $345.5 billion.

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.This graph shows private construction spending for residential and non-residential (SAAR in Billions). While private residential spending has declined significantly, spending for private non-residential construction has been strong.

The second graph shows the YoY change for both categories of private construction spending.

The normal historical pattern is for non-residential construction spending to follow residential construction spending. However, because of the large slump in non-residential construction following the stock market "bust", it is possible there is more pent up demand than usual - and that the non-residential boom will continue for a longer period than normal.

The normal historical pattern is for non-residential construction spending to follow residential construction spending. However, because of the large slump in non-residential construction following the stock market "bust", it is possible there is more pent up demand than usual - and that the non-residential boom will continue for a longer period than normal.Right now the recent trend is holding: residential construction is declining, but private non-residential construction is still strong.