by Calculated Risk on 4/05/2014 03:07:00 PM

Saturday, April 05, 2014

Research: Labor Force Participation Rate

Projecting the labor force participation rate is very complicated. There are many conflicting trends that must be considered ...

For those interested in the numbers, I recommend this recent article from BLS economist Mitra Toossi: Labor force projections to 2022: the labor force participation rate continues to fall

The U.S. civilian labor force—the number of people working or looking for work—has gone through substantial changes in its size and demographic composition over the last half of the 20th century. During the 1970s and 1980s, the labor force grew vigorously as women’s labor force participation rates surged and the baby-boom generation entered the labor market. However, the dynamic demographic, economic, and social forces that once spurred the level, growth, and composition of the labor force have changed and are now damping labor force growth. The labor force participation rate of women, which peaked in 1999, has been on a declining trend. In addition, instead of entering the labor force, baby boomers are retiring in large numbers and exiting the workforce. Once again, the baby-boom generation has become a generator of change, this time in its retirement. Moreover, the jobless recovery of the 2001 recession, coupled with the severe economic impact of the 2007–2009 recession, caused disruptions in the labor market. In the first 12 years of the 21st century, the growth of the population has slowed and labor force participation rates generally have declined. As a result, labor force growth also has slowed. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) projects that the next 10 years will bring about an aging labor force that is growing slowly, a declining overall labor force participation rate, and more diversity in the racial and ethnic composition of the labor force.There are a number of tables in the article showing the trends for various cohorts. An excellent resource!

The U.S. labor force is projected to reach 163.5 million in 2022. The labor force is anticipated to grow by 8.5 million, an annual growth rate of 0.5 percent, over the 2012–2022 period. The growth in the labor force during 2012–2022 is projected to be smaller than in the previous 10-year period, 2002–2012, when the labor force grew by 10.1 million, a 0.7-percent annual growth rate.

WSJ Employment Graph ignores Demographics, Needs Correction

by Calculated Risk on 4/05/2014 01:34:00 PM

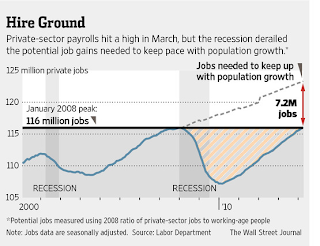

I've been reading several articles on the March employment report this morning, and I have to comment on the graph below.

From the WSJ: U.S. Reaches a Milestone on Lost Jobs

Private-sector payrolls hit a record 116.09 million, passing the peak set in January 2008, but they are far below where they would be if the labor market's trajectory weren't interrupted. And government jobs remain well short of their high point.And the article had the following graph for private employment:

To create this graph, the WSJ used the ratio of private employment in January 2008 (115.977 million) to the total civilian noninstitutional population. The dashed line assumes that this ratio stayed constant since January 2008 - and seems to suggest that there should be 7.2 million more private sector jobs today.

To create this graph, the WSJ used the ratio of private employment in January 2008 (115.977 million) to the total civilian noninstitutional population. The dashed line assumes that this ratio stayed constant since January 2008 - and seems to suggest that there should be 7.2 million more private sector jobs today.This is nonsense. This ignores the decline in the participation rate due to demographics. I've been discussing the decline in the participation rate for several years, and this has attracted significant attention recently.

To review: the participation rate has declined for both demographic and cyclical reasons. There are several key demographics trends, the two most obvious being the large cohort (baby boomers) moving into lower participation age (over 55), and the long term trend of more younger people (16 to 24) staying in school. The cyclical decline is due to the lingering effects of the housing bust and financial crisis on the labor market. There is an ongoing discussion about how much of the decline has been due to demographics, and how due to the effects of the great recession. I think more than half is demographics (other research suggests about half, some suggests less).

If we just looked at demographics, the civilian noninstitutional population for the prime working age group (25 to 54) has declined by 1.5 million people since Jan 2008! So ignoring the young and the old, we'd expect fewer workers today - not more. That would be incorrect too since many people continue to work past 55 (and many young Americans still work).

Here is a table of some of the demographic changes over the last 6 years:

| Changing Demographics, Civilian noninstitutional population, Jan 2008 to Mar 2014 (000s) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| 16 to 24 | 25 to 54 | 55+ | |

| Jan-08 | 37,480 | 125,916 | 69,320 |

| Mar-14 | 38,858 | 124,406 | 82,287 |

| Change | 1,378 | -1,510 | 12,967 |

1) There are now more people in the 16 to 24 age group (with a declining participation rate because more people are staying in school). This pulls down the overall participation rate.

2) There are fewer people in the prime working age group.

3) There are many more people in the older age group. Note: Demographics gets complicated. The participation rate is increasing for older age groups, but the participation rate for each cohort is declining as they move into older age groups.

The bottom line is this WSJ graph is nonsense - and bad enough that the WSJ should remove it from the article.

Schedule for Week of April 6th

by Calculated Risk on 4/05/2014 09:15:00 AM

This will be a light week for economic data.

3:00 PM: Consumer Credit for February from the Federal Reserve.

7:30 AM ET: NFIB Small Business Optimism Index for March.

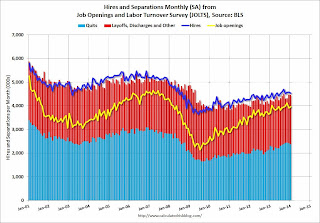

10:00 AM: Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey for February from the BLS.

10:00 AM: Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey for February from the BLS. This graph shows job openings (yellow line), hires (purple), Layoff, Discharges and other (red column), and Quits (light blue column) from the JOLTS.

The number of job openings (yellow) were up 7.6% year-over-year compared to January 2013, and Quits decreased in January and were up about 3% year-over-year.

7:00 AM: The Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA) will release the results for the mortgage purchase applications index.

10:00 AM: Monthly Wholesale Trade: Sales and Inventories for February. The consensus is for a 0.5% increase in inventories.

2:00 PM: FOMC Minutes for the Meeting of March 18-19, 2014.

8:30 AM: The initial weekly unemployment claims report will be released. The consensus is for claims to decrease to 320 thousand from 326 thousand.

Early: Trulia Price Rent Monitors for March. This is the index from Trulia that uses asking house prices adjusted both for the mix of homes listed for sale and for seasonal factors.

2:00 PM ET: The Monthly Treasury Budget Statement for March.

8:30 AM: The Producer Price Index for March from the BLS. The consensus is for a 0.1% increase in prices.

9:55 AM: Reuter's/University of Michigan's Consumer sentiment index (preliminary for April). The consensus is for a reading of 81.0, up from 80.0 in March.

Friday, April 04, 2014

Public and Private Sector Payroll Jobs: Carter, Reagan, Bush, Clinton, Bush, Obama

by Calculated Risk on 4/04/2014 07:17:00 PM

By request, here is an update on an earlier post through the March employment report.

Note: I added President Carter.

Important: There are many differences between these periods. Overall employment was smaller in the '80s, so a different comparison might be to look at the percentage change. Of course the participation rate was increasing in the '80s (younger population and women joining the labor force), and the participation rate is declining now. But these graphs give an overview of employment changes.

The first graph shows the change in private sector payroll jobs from when each president took office until the end of their term(s). President George H.W. Bush only served one term, and President Obama is just starting the second year of his second term.

Mr. G.W. Bush (red) took office following the bursting of the stock market bubble, and left during the bursting of the housing bubble. Mr. Obama (blue) took office during the financial crisis and great recession. There was also a significant recession in the early '80s right after Mr. Reagan (yellow) took office.

There was a recession towards the end of President G.H.W. Bush (purple) term, and Mr Clinton (light blue) served for eight years without a recession.

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

The first graph is for private employment only.

The employment recovery during Mr. G.W. Bush's (red) first term was very sluggish, and private employment was down 841,000 jobs at the end of his first term. At the end of Mr. Bush's second term, private employment was collapsing, and there were net 462,000 private sector jobs lost during Mr. Bush's two terms.

Private sector employment increased slightly under President G.H.W. Bush (purple), with 1,510,000 private sector jobs added.

Private sector employment increased by 20,955,000 under President Clinton (light blue), by 14,717,000 under President Reagan (yellow), and 9,041,000 under President Carter (dashed green).

There were only 1,998,000 more private sector jobs at the end of Mr. Obama's first term. Just over one year into Mr. Obama's second term, there are now 4,690,000 more private sector jobs than when he initially took office.

A big difference between the presidencies has been public sector employment. Note the bumps in public sector employment due to the decennial Census in 1980, 1990, 2000, and 2010.

A big difference between the presidencies has been public sector employment. Note the bumps in public sector employment due to the decennial Census in 1980, 1990, 2000, and 2010.

The public sector grew during Mr. Carter's term (up 1,304,000), during Mr. Reagan's terms (up 1,414,000), during Mr. G.H.W. Bush's term (up 1,127,000), during Mr. Clinton's terms (up 1,934,000), and during Mr. G.W. Bush's terms (up 1,744,000 jobs).

However the public sector has declined significantly since Mr. Obama took office (down 738,000 jobs). These job losses have mostly been at the state and local level, but more recently at the Federal level. This has been a significant drag on overall employment.

Looking forward, I expect the economy to continue to expand for the next few years, so I don't expect a sharp decline in private employment as happened at the end of Mr. Bush's 2nd term (In 2005 and 2006 I was warning of a coming recession due to the bursting of the housing bubble).

A big question is when the public sector layoffs will end. It appears the cutbacks are mostly over at the state and local levels, but there are ongoing cutbacks at the Federal level. Right now I'm expecting some increase in public employment in 2014.

Comment on Jobs Recovery and Policy

by Calculated Risk on 4/04/2014 03:28:00 PM

The U.S. achieved a minor milestone today with the number of private sector payroll jobs finally exceeding the pre-recession peak. This raises a few of key points:

1) This doesn't include growth of the labor force and population.

2) Total employment is still below the pre-recession peak because of all the public sector layoffs (see previous post for a table of annual public sector job losses). Total employment should be above the pre-recession peak this summer.

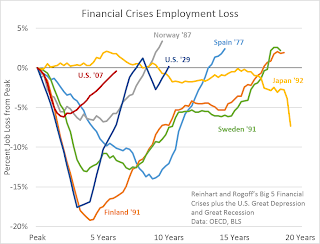

3) Even though it took 6+ years to exceed the previous employment peak, this is actually better than most recoveries from a financial crisis. (Note: this recovery was during a period of declining participation - partially due to demographics - and that makes this milestone even better).

From Josh Lehner today: Getting There. Financial Crises Edition.

From Josh Lehner today: Getting There. Financial Crises Edition.

[T]he graph compares employment loss for Carmen Reinhart and Ken Rogoff’s so-called Big 5 financial crises with the U.S. Great Depression and Great Recession. Using Reinhart and Rogoff’s great work on historical financial crises, our office previously looked into comparing the Great Recession with these historical financial crises to see how the current cycle stacked up. Overall the Great Recession was your “garden-variety, severe financial crisis” as Rogoff once said, but in terms of employment, the U.S. has actually done fairly well when compared with these other, major crises. Not good enough overall to avoid mass unemployment and lackluster growth, but in the context of historical financial crises, the U.S. employment picture is better than most.Point 3 is critically important for policy.

In 2009, many of us argued the current recovery would be sluggish because of the causes of the recession (a housing bust that led to a financial crisis). This is why I never understood why projects needed to be "shovel ready" to be included in the early 2009 stimulus package. Look at the construction job losses in the previous post, clearly infrastructure investment could have been spread out over several more years.

Unfortunately, when the stimulus was being introduced, many opponents argued the economy would recover quickly without the stimulus (obviously poor economic analysis). Even the Obama administration mostly thought the recovery would happen sooner (hence the unfortunate pivot to austerity).

Even today some policymakers don't understand what happened. As an example, from U.S. Congressman Kevin Brady (R-TX), chairman of the Joint Economic Committee: “That it took six long years for America's economy to simply return to break even for Main Street jobs is compelling proof of President Obama's disappointing economic leadership." Unfortunately that shows the "chairman of the Joint Economic Committee" is ignorant of the nature of recoveries from a financial crisis. Very sad.

What we should actually be doing is asking why the recovery was this good relative to other financial crisis. What did we do correctly? And what did we do wrong?

Wrong is easy - some of the stimulus was a clear mistake. As an example, the tax credit for business investment - when there was already too much supply - was a mistake. And research by Atif Mian and Amir Sufi suggests that "cash for clunkers" wasn't effective:

[A]lmost all of the additional purchases under the program were pulled forward from the very near future; the effect of the program on auto purchases is almost completely reversed by as early as March 2010 – only seven months after the program ended. The effect of the program on auto purchases was significantly more short-lived than previously suggested. We also find no evidence of an effect on employment, house prices, or household default rates in cities with higher exposure to the program.And of course I vigorously opposed the expensive and ineffective housing tax credit that was originally proposed by Senators Johnny Isakson (R) and Joe Lieberman (I). I opposed the tax credit early and often. The tax credit for buying new homes was especially dumb. A key problem during the housing bust was the excess supply of vacant housing units, and incentivizing people to buy new homes (and add to the supply) made no sense at all.

But clearly most of the stimulus was effective, and I think more infrastructure investment (help with construction employment) - and more aid to states (keep more teachers, police and firefighters employed) - would have been very helpful.

Luckily the track record of the Federal Reserve was better than for fiscal policy makers. Although Bernanke was slow to recognize what was happening - and he underestimated the severity of the crisis (remember "contained to subprime"?) - when he finally understood what was happening, the Fed was very effective. Bernanke's critics argued that his policies would lead to inflation (wrong) and a collapse in the dollar against other currencies (also wrong).

The key points are this recovery is better than most from a financial crisis and policymakers did many of the correct things (although they could have done better).