by Calculated Risk on 6/11/2007 06:09:00 PM

Monday, June 11, 2007

Bear Stearns Responds

Dryfly can stop holding his breathe!

David Malpass, chief economist at Bear Stearns, kindly responded to my email today (see this post for background: Bear Stearns and RI as Percent of GDP). I don't have permission to post his email, but basically he says the chart is as intended - the chart uses chained 2000 dollars for both Residential Investment (RI) and GDP, and then presents the ratio of RI (chained 2000 dollars) as a percent of GDP (chained 2000 dollars).

UPDATE: Professor Tim Duy provides a Fed paper that explains the error in using real ratios from chained series, and recommends the approach I used. See: A Guide to the Use of Chain Aggregated NIPA Data, Section 4. Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

This graph shows Residential Investment as a percent of GDP (red), and using a ratio of chained dollars (dashed purple, Bear Stearns).

At the least, the chart in the Bear Stearns research note (not shown), is mislabeled. Note that Bear Stearns shows RI as a percent of GDP for Q1 2007 as 4.5%, but in reality it is 5.07%. Here are the numbers from the BEA:

Q1 GDP: $13,613.0 Billion

Q1 RI: $690.5 Billion

RI as % of GDP: 5.07%

I frequently use real quantities (adjusted for inflation), but one of the exceptions is when I normalize by some other factor. In this case, I normalized RI with GDP.

David Malpass argues "Our graph is relevant in thinking about the number of

people employed in the sector, the useage of commodities, etc.". I don't share his view. I think normalizing by GDP (red line) provides a better view of how much of GDP is dedicated to housing.

And finally, I'd like to note that RI is not the same as housing prices (see What is "Residential Investment"?). Most of RI is value put in place for new construction, home improvement spending, and commissions. Only brokers commissions are directly tied to housing prices (although there is usually more RI when prices go up significantly). So when we talk about RI, we are mostly talking about construction materials and labor costs.

Paulson v. Bear, Again

by Anonymous on 6/11/2007 05:44:00 PM

Sir, Your articles "Hedge funds hit at subprime aid for homeowners" and "Fears over helping hand for mortgage defaulters" (June 1) mischaracterised our efforts to prevent market manipulation as somehow against loan modification. To be absolutely clear, we have no objection to loan modification; however, we are vehemently opposed to market manipulation.

Paulson & Co and other major financial institutions are concerned about credit protection sellers providing non-economically motivated credit support to mortgage-backed securities (MBS) trusts for the sole purpose of artificially influencing the value of the credit protection sold. This can be done, for example, by purchasing defaulted mortgages worth less than par from the trusts that hold them at par value. Because the credit default swaps (CDS) market is so much larger than the amount of the underlying MBS securities, a credit protection seller can spend a small amount on such credit support and achieve huge gains on related derivatives positions.

Our concerns about manipulation arose when we heard about plans by certain market participants to sell credit protection and simultaneously to provide credit support to the underlying MBS trusts. Although these transactions are market-manipulative and therefore prohibited under securities laws, our firm proposed that the International Swaps and Derivatives Association amend the language of its CDS documentation expressly to prohibit such transactions. ISDA's staff asked us to help them gather views from interested market participants, including credit protection buyers, in order to hold a meaningful discussion of the issue. The language we proposed in no way references or restricts loan modification.

The manipulative transactions we are seeking to prevent have nothing whatsoever to do with loan modification or helping subprime borrowers. Your articles suggest that our firm, as the organiser of a "group of more than 25 hedge funds", opposes loan modification. To the contrary, we support loan modification as the fastest way to resolve troubled loans in a way that helps keep borrowers in their homes. What we oppose is deliberate market manipulation.

Michael Waldorf,

Paulson & Co

So we can all stand down. It's just one of those things that is clearly "prohibited under securities laws," but apparently not prohibited under ISDA deal documents.

(Hat tip, jck)

Harvard on Housing: Too much inventory

by Calculated Risk on 6/11/2007 12:06:00 PM

From MarketWatch: Pulse on housing

It's still too early to tell exactly when this housing slump is going to end, with house prices just beginning to soften, mortgages at risk of defaulting beginning to hit reset dates and lending standards that are starting to tighten, according to researchers at the Harvard University's Joint Center for Housing Studies.This is a stunning statistic:

One thing's for sure: Before the sun shines again on the housing industry, a good amount of excess inventory will have to be sold, according to the center's "State of the Nation's Housing" report, released Monday.

"In just one year the number of households spending more than half their income on housing increased a startling 1.2 million to 17 million in 2005," Rachel Drew, research analyst for Harvard's Joint Center of Housing Studies, said in a news release.I believe this isn't correct:

"If you were an economist, you would think that prices would have fallen precipitously," [Nicolas P. Retsinas, director of the center] said.I believe most economists recognize housing suffers from "sticky prices" and they wouldn't have expected a precipitous decline in prices, rather they would expect real prices to decline over several years.

Here is the report: The State of the Nation's Housing 2007

And the Joint Center for Housing Studies home page.

Efficient Markets

by Anonymous on 6/11/2007 09:46:00 AM

From "Show me the money: Ex US officials swell hedge funds' ranks":

Industry alarm about a US regulatory clampdown, however, has risen amid calls from some congressional lawmakers for better transparency despite assertions by the US Treasury that the sector's self-policing is adequate.

Executives and insiders say, however, that a feared regulatory assault only partly explains the race to hire well-connected officials.

"Everyone brings something to the table," said an individual at one private equity firm who requested anonymity.

He said former government officials can provide access, if needed, to regulators, but that such people are usually hired for their intellect and frequently because they had successful business careers before entering government. . . .

John Snow was appointed chairman of Cerberus Capital Management in October months after departing the Treasury, joining a private equity firm that already counts former US vice president Dan Quayle on its payroll. . . .

Hey, hedgies! I'm available! I have a towering intellect, I used to work for a living, and I once got a B+ in American Government 106! I'd take losing positions for half what you're paying these guys! Think about it! You could still charge exhorbitant management fees to your befuddled investors, but you could pocket half of it!

New York Times, "Goldman Runs Risk, Reaps Rewards":

Lloyd Blankfein’s makeover from frumpy gold salesman to chief executive has a bit of a reality-TV feel to it. Less than a decade ago, he could be seen in shorts at a golf outing, tube socks stretched to his knees, 50 pounds heavier, and toting his BlackBerry in the same plastic bag as his bagel with cream cheese. Today, he dons navy pinstripes and a power tie and, having just returned from a business trip to Turkey, enjoys conversing about the Ottoman Empire.

Hey, Goldman! I've read all Dorothy Dunnett's novels; I can talk about the Ottoman Empire, too! I used to wear pantyhose with open-toed shoes, while playing in a darts league, while carrying a tiny handbag that had nothing in it but some cash, my keys, and a big bottle of aspirin!

All prospective employers: Leave your phone number in the comments!

This has been another illustration of the Nash Equilibrium. (You're welcome. Really.)

Sunday, June 10, 2007

Unsold houses pile up

by Calculated Risk on 6/10/2007 05:52:00 PM

From U.S. News: The Spring of Home Sellers' Discontent

... inventories of unsold homes in major metro areas rose another 5 percent in May, according to Zip Realty, nearly a one-third increase over the same time last year. And while home builders have cut back on construction by about as much, "they still have a lot of money in the ground," Credit Suisse housing analyst Ivy Zelman says of the raw land still on builders' books. "And the only way to get their cash back is to build more houses."If the NAR number follows Zip Realty for May, then the May existing home inventory levels will be over 4.4 million - another all time record - and total inventory, including new homes, will be approaching 5 million units.

UPDATE: Add graphs based on Zip estimate of inventory increase for May.

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.This graph is based on the Zip Realty estimate of the inventory increase for existing homes in May. Inventory usually increases in May, but the levels of inventory (already an all time record) are a reason for concern.

A 5% increase would put inventory at 4.41 million. A word of caution: we have seen the Zip Realty estimate vary significantly from the NAR estimate in the past, probably because the Zip Realty numbers are only a subset of the total NAR numbers.

The second graph shows the impact on the "months of supply" using the Zip Realty estimate for inventory, and the NAR estimate for pending home sales (down 3%).

The second graph shows the impact on the "months of supply" using the Zip Realty estimate for inventory, and the NAR estimate for pending home sales (down 3%). This would put months of supply at or above 9 months - very close to my estimate of the peak this summer of 9.5 months. Once again, this is just an estimate.

Original post continues:

Meanwhile the homebuilders keep building, because they can't sell the land.

[Land sales have] "just really slowed to a complete trickle with very few buyers of any type out there ... that's part of the reason why you do see many home builders resorting to selling spec homes because there's really a way of liquidating the land portfolio."

Homebuilder Hovanian, June 1, 2007

"it's probably going to take until next summer before things finally bottom out,"

Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody's Economy.com, June 10, 2007

“Uneconomic Transactions,” Or Why I Hate Wall Street

by Anonymous on 6/10/2007 09:06:00 AM

So what has given rise to today’s latest installment of WSDS (Wall Street Derangement Syndrome)? In this post of the other day we were attempting to wade through the undistinguished reporting on this current hullabaloo subject of hedge funds accusing investment banks generally and Bear Stearns specifically of “market manipulation.” I observed at the time that, among other things, I couldn’t figure out what sort of mortgage-security-related transactions Bear was alleged to have engaged in: modifications? Repurchases? Purchases of mortgages? Purchase of bonds? Lots of people are focused on what motive Bear might have to do something or other with a subprime RMBS/ABS, the idea being that some action could be taken to prevent write-downs on a security or set of them, such that Bear would avoid making a payout to hedge funds who purchased credit protection from Bear on these “reference” securities. What has been making me crazier than usual is that I can’t get a clear fix on what this “action” is that Bear has been alleged to have taken.

Here’s a new piece of reporting on this, which I have not (yet) found on the web. The source is Dow Jones Newswire, “Artful Hedge Trimming On Wall Street,” by Steven D. Jones (thank you, Brian):

Hedge funds, which insure mortgage-backed securities by purchasing credit default swaps, have complained that some techniques used to restructure loans reduces the value of their swaps. That's because in renegotiating loan terms lenders may pull loans out of the underlying loan pool in a security and reduce the likelihood of default. . . .I confess that there’s something about Harvey Pitt (who last I knew is a former SEC Chairman as well as a former Commisioner, but whatever) making claims about the credibility of the subprime mortgage market that sends my personal irony tolerance well into the danger zone, so let’s not get into consideration of the source here. I first want, however, to highlight the utter absurdity of the claim that, after all the fraud, criminally loose underwriting, and perfectly disgusting capital resource misallocation that has collectively been known as the “subprime mortgage market” in the last few years, it can be asserted with a straight face that there’s any credibility left there to blow.

But what may appear to be a tempest in a teapot goes to the heart of the swap business. Renegotiating loan terms is one thing, but removing troubled loans from portfolios specifically to avoid paying losses on credit default swaps may erode the value in the swap market that is essential to subprime lending.

"What is objectionable are non-economic transactions in order to avoid making payments to holders of derivative positions," says Harvey Pitt, a former Securities and Exchange Commissioner and advisor to hedge funds in the matter.

When Wall Street firms buy worthless loans out of a portfolio they eliminate the risk of paying off the credit protection the firms sold to hedge funds. Renegotiating loans with homeowners doesn't affect swap investors and benefits lenders and homeowners. But just buying and removing defaulted mortgages from loan pools to avoid paying derivative holders weakens the system, says Pitt.

"My concern is that this type of manipulative conduct will undermine the credibility of the subprime mortgage market," he says.

Ditto goes for the unironic claim that “the swap market . . . is essential to subprime lending.” Well, sure. Flame-retardant suits are essential to surviving the process of driving a motorcycle up a steep ramp at 150 mph and shooting over a series of raging bonfires, but there’s also the idea that you could just not drive a motorcycle up a steep ramp at 150 mph and shoot over a series of raging bonfires and then you wouldn’t really need that fireproof get-up. The “credibility” Pitt is talking about is the “credibility” of stupid subprime lending, a party that’s been and done and over now that the “swap market” has decided it’s no longer a great “risk-free” trade. You want someone to shed tears over that, you’re on the wrong blog.

That nonsense aside, notice once again how difficult it is to really get a handle on what the alleged behavior here is. The implication is that modifying or “restructuring” a troubled loan is OK, but buying a loan out of a pool in order to restructure it is not OK. On the face of it that makes zero sense, and so what is necessary is the further claim that the latter—buying a loan out of a pool in order to modify it—represents a dishonest act by the mortgage servicer because it is a “non-economic” transaction for the servicer. That is, what is assumed is the servicer will lose money doing it that way, and if the servicer is volunteering to lose money, there must be a reason, and the reason must be to avoid paying out on the swaps, which would involve a much bigger loss than the loss on the restructured loans.

Here’s where we need to get all unsloppy with our language and UberNerdly with our concepts, members of the press. I have yet to see anyone in any published source make any reference to an actual shelf or issue in which this practice is alleged to have occurred, so I can’t go to EDGAR, find the deal documents, and tell you exactly what rights and obligations that specific deal gives to a specific servicer in regards to modifications. Until such time as certain folks quit making nonspecific allegations in the press that the rest of us can’t verify because we can’t see what deal you’re talking about—sure, a cynical person might see this as an attempt at market manipulation by the hedgies, designed to drive investors out of those “manipulated” tranches and therefore drive their prices down to increase the swap payout to the hedgies, but of course that would be, like, so totally unfair and mean and unsympathetic besides like totally lacking in actual evidence OMG so I’m not going to do any such thing—we are stuck trying to measure the “credibility” of the manipulation argument by looking at how subprime RMBS/ABS deals usually work. So please take the following with that in mind: there may be deals out there that give a servicer rights or obligations I am not aware of. In what follows I am merely working with what I do know about all the deals I’ve ever seen. I have not seen them all; subprime securitizations have never been a specialty of mine, God help me.

Recall the basic point of securitizing loans: if what you are trying to do is get some risk off your books, you have to get it off your books. This gets you to securitization accounting 101: securitizations can be on-balance sheet debt financings, or off-balance sheet “true sales.” Without wading into the weeds here, the point is that you only get certain liabilities and risks “off your books” if the securitization involves a true sale of the loans to the SPV (the trust entity that actually owns the loans on behalf of the security investors). There are a whole lot of financial transactions, like certain repos, swaps, and collateralized financings, legit and “sham,” that involve party A transferring an asset to party B, but with some understanding that party B can send it right back if it turns out to be “non-economic,” or that party A can demand it back (call it) without market risk. Such transactions are not “true sales”; in the true sale, the seller relinquishes control of the asset, the buyer assumes the risk of the asset, and any return of the asset to the seller would have to be “at market.”

There are, in fact, on-balance sheet mortgage securitizations, but as I believe that is not what we’re talking about in the current situation, I am ignoring those. It would be a lot harder to make claims about “manipulation” if the “reference security” were an on-balance sheet securitization; by definition the sponsor of an on-balance sheet security carries the risk and all “restructurings” would have a clear presumption of being “economic” for the sponsor/servicer.

Theoretically, any “restructuring” of a true off-balance sheet securitization would be economically neutral for the sponsor/servicer. The “economics” now belong to the investors who put capital into the deal. The servicer is paid a servicing fee, and certainly in a badly-written servicing agreement there could be perverse incentives for a servicer to increase its compensation by taking actions that are “non-economic” to the bondholders. We do not particularly seem to be alleging this in present circumstances.

This really is an important point: the sponsor/servicer may not “control” the collateral in an off-balance sheet securitization. The difference between “servicing the loans” and “controlling the collateral” may not be always obvious, but that’s why you hire lawyers to write 80-page pooling and servicing agreements. In all cases, without exception, the servicer must have a fiduciary duty to the trust—which has the fiduciary duty to the bondholders—to service the loans such that gain/loss to the deal is the ultimate legitimate consideration.

The whole hoopla over modifications tends to involve the assumption—fact-based or faith-based—that servicers are modifying loans mostly to benefit borrowers (usually unspoken here is that they do that at regulatory behest; they are not usually assumed to be that altruistic) or to benefit the servicers themselves. They do that either by increasing/maintaining servicing compensation for loans, or by virtue of the fact that the servicer is also the sponsor, the sponsor holds the residual interest in the security (the right to any interest income left over after paying the bondholders, covering losses, and maintaining overcollateralization), and therefore the servicer is identified with the residual, not the funded tranches.

The Fitch report we were looking at the other day, for instance, is in aid of dealing with that latter problem. Fitch declared, basically, that while servicers would clearly be within their rights to modify loans as a loss mitigation practice, those modifications would be taken into account when it came time to “step down” the deal or release the overcollateralization. Short version of what that means: the residual holder would not be able to get its hands on money faster by modifying loans with the sole intent of making the delinquency/default “triggers” look better than they really are.

That might suggest that “the problem”—real or imagined, and I’m not sure how much a lot of this wasn’t imagined—of modifications is on its way to being solved, at least from the perspective of the bondholders. The American Securitization Forum just issued recommendations for standardized deal document language regarding mods that is an attempt to formalize all this on new deals. My own personal view of the whole situation is that there’s nothing earth-shatteringly innovative in the ASF guidelines; it’s not a “new way” of dealing with the ancient problem of modifying loans. It’s a way of sort of dealing with the reality that we have too many mods to do, not that we’re modifying at all.

That is, if the underlying loans weren’t such unspeakable horrors to start with, we wouldn’t be here. But I’m not hearing any market participants—not Fitch, not ASF, not, God help us, a certain former SEC Commissioner—volunteering as how that might be the case. As CR likes to say, “mistakes were made.” The old subprime credit guidelines are “no longer operative.” Let’s all be “constructive” and ignore how we got into this horrible mess in favor of obsessing endlessly about the minor details of how we’re going to try to make lemonade out of it.

OK, so how come this hasn’t, actually, “settled” this modification problem? It’s because Fitch and ASF and those nosy-parker regulators are thinking about the interests of bondholders and sponsor/servicers—with the occasional nod to those borrowers. It appears that we have not yet worried sufficiently about the swappers. That is to say, in all of this we have been considering modifications as “economic” transactions for somebody. They are supposed to be “economic” for the bondholders, to whom the primary, ruling, overarching fiduciary duty here is owed. “Economic” does not mean “at a profit”; the whole great long Fitch document we just looked at is dealing with the problem that “loss mitigation” is about taking the smallest loss possible, not preventing loss entirely and certainly not making a buck. Servicers are on notice that they cannot modify loans unless it is the “best execution” in reference to the loss taken by the deal as a whole, not any class of securities within it, up to and importantly including the residual. If acting in the best interest of the deal is “non-economic” for the servicer, well, bummer. That’s what a fiduciary duty can do for you. Servicing mortgage loans also has risks. This is not a particularly controversial idea to any adult mortgage servicer I know.

What you haven’t seen in the Fitch or the ASF document, however, is any direct discussion of this question of taking a loan out of a security in order to modify it, as opposed to modifying a loan that remains in the security. And that seems to be the big to-do today with the hedgies. Why is that? Well, it is never the point to buy a loan out of a pool in order to do anything with it whatsoever, including but not limited to modifying it. These are not “managed” pools; that’s the whole “off-balance sheet true sale” thingy. The deal documents (at least the REMIC ones) that I am aware of do not give the trust the right to sell loans out of the pool for gain for any reason; the underlying loans are “held to maturity” in the security, not “held for sale.”

All the trust can do is force repurchase of certain loans in a very specific circumstance: if the loan is defective, if it violates the reps and warranties of the loan purchase agreement, or it experiences an EPD and hence invokes the EPD covenant, the trust forces the sponsor to either buy it out of the security at par, or, in most deals, to substitute another, substantially similar, non-defective loan in its place. The latter is an option for the sponsor, and it is quite often not a practical choice for a number of reasons.

It is important to understand the “economics” of this particular issue: the most likely result is that nobody wins. The security gets paid par, which limits its loss, but the security doesn’t make money by returning principal early. That’s supposed to teach you not to buy junky loans from people that will have to be put back; there must be some risk to the security in put-backs or else the crap these investors buy would be even worse than what it is today. (There’s a moral there: put-backs are a “crisis” these days because nobody ever thought they’d have to deal with them; the belief they’d never have to deal with them allowed this ridiculous loosening of guidelines.)

The sponsor buys the loan back at par—it does not owe a penalty premium to the security to “make up the loss”—but it now owns a wretched junk loan that is almost guaranteed to be, if not actually “worthless,” then worth a whole lot less than par. That’s supposed to teach you not to sell junk loans or make misrepresentations when you sell loans.

To sum up, this particular means of “selling” a loan out of a security is “non-economic” to everyone involved, but it is supposed to be non-economic to everyone involved. I repeat: these are not “at market” sales where there would be a gain to the deal. They are “money back warranties,” if you will. If you’ve ever gotten your “money back” on a defective toaster, only to discover that it’s approximately 50% of the price of a new toaster, you understand how this game works.

So I for one do not think we are probably talking about true buybacks here, although anything is possible. There is one other way a loan can be “bought out of” a security, and that is a clause that is typically (but certainly not universally) present in a security servicing agreement that gives the servicer the right, but not the obligation, to buy a seriously delinquent loan (at least 90 days past due, and often at least 90 but no more than 120 days past due) out of the security. Let me say first that we are talking about private-issue non-guaranteed RMBS, not Fannie or Freddie or Ginnie MBS. In those latter, guaranteed securities, either the servicer or the guarantor has the obligation to buy a delinquent loan out of the pool, because in a guaranteed security the bondholders do not take principal losses. For our purposes, we’re talking about securities where bondholders have to take write-downs if they occur. This is why the defaulted-loan removal clause is a right, but not an obligation, of the servicer; if it were an obligation it would be a “guarantee,” and that whole “off-balance sheet” risk-layoff thingy would be a major problem.

You therefore ask: so why the hell would a servicer ever want to do such a stupid thing as buy a seriously delinquent loan out of the pool, when it has the right to leave it there and make the security eat the loss? There are certainly situations in which everyone involved gains by this practice. Imagine that the loan in question is an ARM, the pool is an ARM-only pool, and the only way to fix up the loan and avoid foreclosure is to modify it to a fixed rate. The deal does not want a fixed rate loan in it; that messes up the net yield and cash-flow and may even violate the prospectus (if the prospectus says there are only ARMs in the pool).

So the servicer buys the loan out at par, which means no principal loss to the deal, modifies the loan to a fixed rate, and either holds it to maturity or sells it as a scratch & dent whole loan or resecuritizes it some day in a “reperforming” or “seasoned” deal. Some folks got a bit concerned in the comments the other day about this “resecuritization” of these loans. You really don’t have to worry, usually, about anybody making any pots o’ money off of this; the whole thing is rarely more than a break even, if that much. And the new security is a junk security, not a “new production” security, so it’s not like anyone is fobbing a seasoned modified loan off on someone else as a new warranted loan.

After all that, the best I can speculate is that Bear is being accused of exercising its right, as servicer, to buy seriously delinquent loans out of these pools, in a manner that is alleged to be “non-economic” for Bear as these are loans a rational servicer would leave in the pool for the bondholders' butts to get bitten by. The allegation is that Bear is willing to do this counter-intuitive thing because 1) doing so means there are fewer seriously delinquent loans in the pool and 2) that means that the step-down triggers do not fail which means 3) the subordinate tranches or OC accounts take fewer write-downs or 4) the subs/OC receive stepped-down payments that increase their value or 5) the tranches in question avoid a rating downgrade and 6) all or any of that means that Bear avoids an even more “non-economic” problem involving the credit default swap payouts. The accusation is that Bear loses a little on buying out these yucky loans, as opposed to losing a lot more by settling with those who bet on the yucky performance of the security.

This, friends, is naked “class warfare.” Who wins? The bondholders get principal back on a loan that would undoubtedly have otherwise generated a loss (if not, it would not be “non-economic” for Bear to buy it out). The bondholders also get a “cleaned up” security that is worth a better market price and that steps down faster to increase returns to the holders of the riskiest tranches. The borrowers get a modification that at least in theory helps them hang onto their homes. Possibly “spillover” rushes for the exits are averted, as the value of these securities is stabilized, if not necessarily improved. The hedgies are screwed, though.

I am sorry this is so long and everything, but we have to look at this in detail, because after all of this I for one want to know just exactly where and when all this so-called “insurance” did anything for the subprime mortgage market that could be called helpful, let alone “essential,” to keeping it going. Let us ask: if we didn’t have all this “insurance,” what would we be doing? We’d be modifying those loans right and left in a desperate attempt to staunch the wounds for the bondholders. Funny, that’s what we’re doing with all this “insurance.”

Would there even be that many wounds if a bunch of bright lights on Wall Street had not had this “insurance” available to it? Take the CDS racket out of the equation, and bagholders would be bagholders, they’d know they were bagholders, and the sense God gave an artichoke might have encouraged them to display markedly less enthusiasm for this crap unless those underwriting guidelines were less ridiculous and the due diligence bore some relationship to “due” and “diligent.” As it stands, I don’t see much here except a huge moral hazard, on the one hand, and simple opportunistic punting, on the other. Is Bear “manipulating” a market? In a market this distorted, how, exactly, are you going to define “manipulation”?

This is the point where the Total Pains in the Ass (TPITA, a sophisticated market term) step in and bloviate about how if we didn’t have all those brave hedgies out there speculating with OPM on defaults, the bond investors wouldn’t have touched this stuff with a ten-foot pole, and then the lenders wouldn’t have made the loans because they wouldn’t have been able to hold that risk themselves, and then those borrowers wouldn’t have been given the “opportunity” to become debt-slaves on some overpriced real estate with granite countertops, if they’re lucky, or in line in bankruptcy court or evicted by the sheriff if they’re really lucky. Maybe some of you all aren’t old enough to remember how we used to have to destroy the village in order to save it, but I for one have no nostalgia for those days.

So yes. If, in fact, Bear is buying delinquent loans in order to modify them when it has a legitimate excuse to modify them but leave them in the deal, I would agree that it certainly has the appearance of “manipulation” and Bear has some ‘splainin’ to do. How these hedge funds can have the unmitigated gall to call the kettle black is beyond my talents to ‘splain. There is an old saw about how the child who murdered his parents gets no sympathy for being an orphan. But it isn’t—it shouldn’t be—about “sympathy.” It wasn’t about “sympathy” when we were reading endlessly about poor deluded borrowers or poor deluded lenders or poor deluded bondholders. It’s about how we’re going to return some rationality, transparency, and accountability to the residential mortgage market before every participant plus all the innocent bystanders go down in flames.

That is not something we will accomplish by continuing to think in terms of eliminating risk, or the possibility of “risk-free trades.” I’m the last person to want to eliminate securitization and go back to the bad old days of excessive risk concentrations in depositories. I have no problems with risk being moved to some holder who can withstand it, or risk being shared, dispersed, or “de-linked” such that any given holder of part of it can withstand that part. This Kool Aid about how you can financial-wizard-engineer some magical step in the chain where risk just disappears and everybody is perfectly hedged is insanity.

Moral hazards have to stop. Everyone has to take a chair. And sit on it. If that puts Bear and Paulson both in jail or in damages, fine by me. Just get them out of the driver’s seat of the residential mortgage market and the price of having a roof over your head before we cripple the real economy past the point of redemption. Please stop helping us.

Saturday, June 09, 2007

Saturday Rock Blogging: Ah, What's Puzzling You?

by Anonymous on 6/09/2007 11:27:00 AM

Happy Saturday, Calculated Risquadores. Forgive me for having been a bit absent for the last few days, but there was a houseguest. And several bottles of wine. At no point was I ever on my knees, howling, while trying to rip my shirt off, but don't think I didn't think about it. (I suppose some of you don't know that alcohol intensifies the effect of hot flashes, and that the temperaure has been in the 90s in my neck of the woods for the past few days. If you wish to imagine something rather more exciting that that, by all means do so.)

I am working on a follow-up post on the Bear-Paulson-Honor-Among-Thieves problem we discussed Thursday morning. You'll get that later. For some reason it also reminded me of this classic tune.

Ah, what's puzzling you

Is the nature of my game, oh yeah

WSJ: Economists See Housing Slump Enduring Longer

by Calculated Risk on 6/09/2007 12:36:00 AM

From the WSJ: Economists See Housing Slump Enduring Longer

Late last year, some economists were saying the market would start bouncing back by the middle of 2007. That hasn't happened, partly because inventories of unsold houses have continued to grow and a surge in mortgage defaults has made lenders much more reluctant to grant credit to people with spotty payment histories.

David Resler, chief economist at Nomura Securities International Inc. in New York, says he is surprised by the degree to which speculation caused builders to overestimate demand, leaving a glut of houses and condominiums.

...

Reflecting this worse-than-expected slump, Mr. Resler recently trimmed his forecast for economic growth in the second half of this year to an annual rate of 2.8% from 3%. He sees about a 33% chance that the U.S. economy will slip into a recession in the next year. If it does, he says, the weak housing market would be largely to blame. Among the risks, he says, are that depreciating home values will make consumers more cautious in spending and that many more housing-related jobs will be lost.

Friday, June 08, 2007

Bear Stearns and RI as Percent of GDP

by Calculated Risk on 6/08/2007 05:26:00 PM

In a June 6th research note, economists at Bear Stearns miscalculated Residential Investment (RI) as a Percent of GDP. This error, in part, led to their conclusion:

"We think house prices, sales, and starts will begin to stabilize."

Bear Stearns, June 6, 2007

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.This graph shows Residential Investment as a percent of GDP calculated correctly (red), and incorrectly (dashed purple, Bear Stearns).

It appears Bear Stearns incorrectly used the chained dollars. This is incorrect because the price deflators are different for both series (RI and GDP). The correct calculation is to use nominal dollars for both series for each period (we are calculating RI as a percent of GDP for each period, so RI is normalized by GDP).

Looking at the dashed line, Bear Stearns chief economist David Malpass recently wrote in Barron's:

"The first-quarter GDP data show residential investment just now getting back to its normal share of GDP (4.5% in the first quarter versus the 4.4% average in the 1990s)."In fact, Residential Investment (RI) as a percent of GDP is currently 5.07% (not 4.5%) and the average in the '90s was 4.08% (not 4.4%).

Here are the numbers from the BEA:

Q1 GDP: $13,613.0 Billion

Q1 RI: $690.5 Billion

RI as % of GDP: 5.07%

I've written Bear Stearns, and I'll post any response or correction.

Orange County Home Sales at Record Low

by Calculated Risk on 6/08/2007 04:04:00 PM

From Jon Lansner at the O.C. Register: Late-May home sales run at 20-year-plus low

If late May home-selling patterns hold for the entire month, we will have just seen the slowest selling May in DataQuick's 20-year history of O.C. home buying. That means even slower than the ugly days of the early 1990s.This is just Orange County, California. And this is just the late-May data. But this fits with the other data points of a further significant slowdown in the housing market occurring right now.

April Trade Deficit, MEW and Interest Rates

by Calculated Risk on 6/08/2007 10:59:00 AM

The Census Bureau reported today for April 2007:

"in a goods and services deficit of $58.5 billion, $3.9 billion less than the $62.4 billion in March"

Click on graph for larger image.

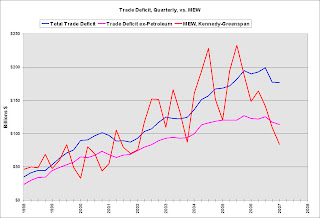

Click on graph for larger image.The red line is the trade deficit excluding petroleum products. (Blue is the total deficit, and black is the petroleum deficit).

Looking at the trade balance, excluding petroleum products, it appears the deficit has peaked and has been declining since the second half of 2005.

The trade deficit, ex-petroleum, appears to have peaked at about the same time as Mortgage Equity Withdrawal in the U.S.

"Interestingly, the change in U.S. home mortgage debt over the past half-century correlates significantly with our current account deficit. To be sure, correlation is not causation, and there have been many influences on both mortgage debt and the current account."

Alan Greenspan, Feb, 2005

The second graph shows the quarterly trade deficit, with and without petroleum, and quarterly mortgage equity withdrawal.

The second graph shows the quarterly trade deficit, with and without petroleum, and quarterly mortgage equity withdrawal.Declining MEW is one of the reasons I forecast the trade deficit to decline in '07. And a declining trade deficit also has possible implications for U.S. interest rates; as the trade deficit declines, rates may rise in the U.S. because foreign CBs will have less to invest in the U.S.. This is why I forecast rates to rise in '07.

And rising rates have negative implications for housing and will probably lead to less MEW. This could lead to a vicious cycle for a short time - less MEW leading to a lower trade deficit, followed by rising rates, follow by less MEW, and repeat.

Thursday, June 07, 2007

Kennedy-Greenspan: Equity Extraction Declines in Q1 2007

by Calculated Risk on 6/07/2007 02:50:00 PM

Here are the Kennedy-Greenspan estimates of home equity extraction for Q1 2007, provided by Jim Kennedy based on the mortgage system presented in "Estimates of Home Mortgage Originations, Repayments, and Debt On One-to-Four-Family Residences," Alan Greenspan and James Kennedy, Federal Reserve Board FEDS working paper no. 2005-41. Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

For Q1 2007, Dr. Kennedy has calculated Net Equity Extraction as $84.0 Billion, or 3.4% of Disposable Personal Income (DPI). Note that equity extraction for Q4 2006 has been revised upwards to $109.1 Billion.

This graph shows the MEW results, both in billions of dollars quarterly (not annual rate), and as a percent of personal disposable income.

Percentage of Household Equity Falls to Record Low

by Calculated Risk on 6/07/2007 01:03:00 PM

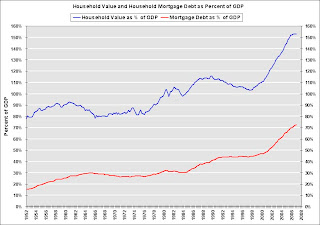

The Fed reports that the value of household real estate increased to $20,771.92 Billion in Q1 2007. This puts the percent household equity at an all time low of 52.7% - despite the recent significant increase in valuations.  Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

This graph shows the percent equity of U.S. households. Note that the scale doesn't start at zero.

Despite the significant increase in valuations in recent years, the percent equity has been dropping - and is now at an all time low of 52.7%. With housing prices falling, the percent of equity will probably continue to fall - even if MEW declines significantly. The second graph shows the value of U.S. household real estate and mortgage debt as a percent of GDP. The value of household real estate will probably start to fall as a percent of GDP, just like in the early '90s.

The second graph shows the value of U.S. household real estate and mortgage debt as a percent of GDP. The value of household real estate will probably start to fall as a percent of GDP, just like in the early '90s.

Mortgage debt as a percent of GDP will probably level out (like in the '90s).

As a reminder, about 1/3 of all households have no mortgage debt. Update: About 1/3 of all owner occupied households have no mortgage debt (their homes are paid off). This comment has nothing to do with renters. However you can't do a direct substraction because the value of these paid-off homes is, on average, lower than the mortgaged 2/3. I just added this comment, because even though the average household has 52% equity in their homes that includes the 1/3 that have 100% equity.

Fed: Mortgage Debt Increased $127.6 Billion in Q1

by Calculated Risk on 6/07/2007 12:32:00 PM

The Federal Reserve released the Flow of Funds report for Q1 2007 today. The report shows mortgage debt increased $127.6 Billion to $9,832.3 Billion in Q1 2007, the slowest increase since Q1 2002.

The calculation of Mortgage Equity Withdrawal (MEW) will probably be available in the next few days, however it appears MEW actually increased slightly in Q1. This is because a significant portion of the lower increase in mortgage debt was due to fewer new home sales

Interest Rates Rising

by Calculated Risk on 6/07/2007 11:22:00 AM

From Dow Jones:

Freddie Mac said that the benchmark 30-year fixed rate mortgage average rose in the week ending Thursday to 6.53% from 6.42% last week.The 30 year fixed rate peaked at 6.76% last July (average for month).

Meanwhile, from the AP: 10-Year Treasury Yield Passes 5 Percent

The 10-year yield broke through 5 percent mark overnight and rose as high as 5.07 percent in mid-morning trading in New York, reaching its highest point since late July.The 10-Year yield peaked at 5.24% last July. I'd expect mortgage rates to rise again next week.

Modifications, Buybacks, True Sales, and Puzzlement

by Anonymous on 6/07/2007 08:38:00 AM

Yes, friends, Tanta is even more puzzled than usual when the subject is hedge funds. May I beg our readers who have more familiarity with this part of the financial markets to help us out here?

The Financial Times and a number of other sources have reported lately that hedge funds are accusing the investment banks--Bear Stearns specifically--of "market manipulation" by modifying deliquent or soon-to-be delinquent securitized mortgages. The hedgies' interest in all this, it appears, is not that they own these bonds--although that is hardly clear to me--but that they have been on the other side of some credit default swaps which means they will lose if the bonds perform better than anticipated.

Reuters reports that the WSJ reports that the issue is "purchases":

NEW YORK (Reuters) - Hedge fund managers are accusing Bear Stearns Cos. of trying to manipulate the market in securities based on subprime mortgages, the Wall Street Journal reported in its online edition.

The confrontation provides a rare look into the complex trading in the mammoth U.S. mortgage market, which played a critical role in financing the housing boom, and the complicated relationships between hedge funds and investment banks, the paper said.

Hedge funds that had sold short such securities made profits when an index tied to a basket of subprime bonds was falling. But the index has recovered in recent weeks, leading to howls of protest from hedge funds, according to the report.

The chief critic, John Paulson of Paulson & Co., a $12 billion fund, says Bear Stearns wanted to prop up faltering mortgages-backed securities by purchasing individual mortgages that were rapidly losing value to avoid doling out billions in swap payments, the Journal reported.

I am not a subscriber to the Wall Street Journal; perhaps someone who read the original article can help us understand this.

Whatever do they mean by "had sold short such securities"? Are we really talking about a CDS trade? No doubt the "index" in question is the ABX, but can anyone help me decipher the actual trade here?

Furthermore, what could "purchasing individual mortgages that were rapidly losing value" possibly mean in this context? Are we talking about repurchases (EPDs and other rep/warranty failures)? Bear would presumably be the "purchaser" in this case if it had originated the loan (or at least sold it to the security trustee), which would make Bear responsible for taking it back (and, in turn, forcing it back onto whatever hapless originator sold it to Bear in the first place).

Much ink has been spilled on the subject of Bear (and other IBs, particularly Merrill) forcing loans back to originators to the extent of forcing originators into bankruptcy. The implication of the Reuters piece is that Bear, specifically, is accused of doing this not to clean up the security (remove the defective loans at a full payoff of principal and accrued interest to the bondholder) but to avoid having to pay out to the hedge counterparties.

If that's what we're talking about--and feel free to correct me if I'm wrong--then we have a nice can of worms here. Contractual buyback provisions are supposed to protect bondholders from defective loan collateral that can sneak into those securities precisely because the loans are sold on a rep and warranty basis. You can do limited (define that any way you choose) due diligence on the loan collateral itself, relying on the data tapes (the specific "representations" supplied by the loan originator) plus a custodian's report on the presence and acceptability of the note and mortgage documents, because the contract allows you to put back anything that violates those reps.

In addition, these contracts almost always specify that a loan is repurchased at par (the price is the unpaid principal balance plus any interest adjustment for the sale timing). That can easily mean that the original buyer bought the loan for 102 and is putting it back at 100. It almost always means that the originator is buying it back at 100 and going to have to sell it for a lot less than that. The idea is that nobody wins, particularly, in this situation.

Nobody is supposed to win. The traditional "par repurchase" is supposed to mitigate certain kinds of moral hazard. In any case, a par repurchase has exactly the same effect on the bondholder as a refinance (full return of principal). In terms of the reported credit quality of the security, it removes a delinquent loan or a loan that looks like it's going to become delinquent or (in the case of certain kinds of fraud) a loan that looks like it will be hard to recover anything from in foreclosure. Some investors are willing to give the benefit of the doubt on some kinds of loan defects; no one (sane) does anything with a loan that has title or legal mortgage problems except put it back. We have been reading about lenders who suddenly find they cannot foreclose or take possession because of sloppy loan closing or mortgage assignment practices. This threat is real.

The problem appears to be the identity of interest issue: the security sponsor owes the investors the duty of selling defective loans back to the originator at par. This is supposed to be expensive for all parties (think of what you "saved" by not doing your due diligence), but less so than not doing it (the same logic applies to modifications). However, the hedgies seem to be alleging that Bear will also either profit or avoid losses on its CDS trades by forcing these buybacks. I don't know about you all, but it sounds to me like time to clarify how many hats Bear is wearing here: does it own any classes of any of these securities? Is it the sponsor, the servicer, and/or the originator of these loans? Is it buying or selling credit protection? Whose position is it hedging?

Whether we are talking about modifications or repurchases or both, all of this raises some ugly accounting issues, it seems. Reuters, again:

FAS 140 governs whether a bank can treat assets held in various asset-backed securities as sales or secured financing. If the asset is treated as a sale, it allows banks to keep it off their balance sheets.

Banks say the standard prevents them from helping borrowers modify loans easily. But market experts have said the complications are also a legal issue related to the terms set out at the time a mortgage-backed security is created.

The board has revisited FAS 140 several times since it was approved in 2000, but Seidman said on Wednesday it has not gotten any easier.

"What has become clear to me is that, when we look at the way investors and analysts treat securities transactions, if there hasn't been a free and clear sale, they are unwinding the accounting and putting assets and liabilities back on the books," Seidman said. "I've come to the conclusion that ... we're going in the wrong direction -- trying to maintain a standard that's taking assets off the books when investors view it as economically still associated with the seller."

Some more clarity on this issue would certainly be helpful. If I am reading this correctly, the issue is whether the sale of the underlying mortgage loans to the security trust is a "true sale" or not. If it is, the securitization is truly "off balance sheet." If it isn't, the securitization is on-balance sheet financing of the originator's mortgage loans.

That, in turn, has something to do with how the securitizer books gain (or loss) on the securitization transaction, but for our present purposes it seems the issue is how much a "true sale" a transaction treated as off-balance sheet can be if the securitizer can, in essence, "control" the collateral (by modifying it or by forcing the trustee to sell loans back to the issuer). Traditionally, when there is "recourse" in a sale, it generally has to be treated as a financing rather than a true sale, since the seller retains not just an obligation for performance of the collateral but presumably then some rights to make good on that obligation in ways (substitute loans, repurchases, mods) that may benefit the seller as much as the buyer. My guess here--I'm just reading the news, folks, so it's a guess--is that the Financial Accounting Standards Board is fixin' to possibly decide that some of these "nonrecourse" transactions are, actually, recourse transactions, and not true sales, and therefore not on the right balance sheet, and ugly ugly ugly.

So, if I'm following all this, a torrent of buybacks which has already forced a lot of originators into bankruptcy and evaporated a lot of market cap at the same time it has weakened some servicers to the point that nobody's even sure about getting payments collected on the remaining performing loans, not to mention accomplishing those foreclosures for the ones the security couldn't get out from under, has now called into question the accounting basis of the whole deal, which means potentially evil ugly nasty restatements for anyone still in a position (this side of BK) to restate, and at the same time it has dragged the curtain away from this "all risk has been hedged" mantra to show that behind that curtain, the transactions supposed to protect investors' interests are in fact so riddled with conflicts of interest that the liability those who thought they were purchasing "credit protection" may have to the unhappy campers who were providing that credit protection could more than overwhelm the benefit of the insurance.

Have I got that right? Anyone who can straighten me out in the comments (or via email) is cordially invited to do so.

Wednesday, June 06, 2007

California: State Senate Passes Bill to Tighten Lending Standards

by Calculated Risk on 6/06/2007 09:57:00 PM

Mathew Padilla notes: State Senate passes bill on tougher loan underwriting

SB 385, passed on a 33-1 vote, requires all state-licensed lenders and brokers to follow federal guidelines issued on Sept. 29, 2006. The bill still must face the Assembly and governor.Here are the key passages from SB 385:

SB 385 does the following:emphasis added

1) directs the DFI to apply the nontraditional mortgage product risk guidance issued by the federal government to state-regulated financial institutions,

2) directs the DOC to apply the risk guidance issued by the Conference of State Bank Supervisors and the American Association of Residential Mortgage Regulators (CSBS/AARMR) to licensed finance lenders and residential mortgage lenders,

3) directs the DRE to apply the risk guidance of CSBS/AARMR to real estate brokers,

4) authorizes all three commissioners to adopt emergency regulations and final regulations to clarify the application of the applicable guidance documents to their licensees as soon as possible,

5) directs all affected licensees to develop policies and procedures to achieve the objectives set forth in the guidance, and

6) requires the Secretary of BT&H toensure that all three commissioners coordinate theirpolicymaking and rulemaking efforts.

Additionally, amendments were added in the Senate Banking, Finance and Insurance Committee to expand the definition of real estate brokers to include a person who engages as a principal in the business of making loans, and makes 8 or more specified loans to the public from the person's own funds. The bill also now provides the Commissioner of DRE with clearer statutory authority to compel brokers to provide more information on their renewal forms relating to the types of licensed activities they had engaged in since their last renewal.

The intent of this bill is to ensure that all mortgage lenders and brokers, regardless of their regulator, are subject to the federal guidance on nontraditional mortgage product risks.

The CSBS reports 35 agencies have adopted the CSBS/AARMR Guidance on Nontraditional Mortgage Product Risks. California is about to join the list.

Meritage Homes Revises Outlook

by Calculated Risk on 6/06/2007 05:06:00 PM

Via CNN Money: Weaker Trends in Home Sales Cause Meritage Homes to Revise Its Outlook for 2007 (hat tip Brian)

Meritage Homes Corporation ... reported today that April and May home sales have been weaker than expected, as reported by other leading homebuilders, and lower than the Company's first quarter order rates. Preliminary net sales for the first two months of the second quarter were approximately 21% lower than the same period last year, and cancellations increased to a rate of 36% of gross orders, from 27% reported in the first quarter 2007.Orders down. Cancellations up. Hope gone.

"We were encouraged by sales and cancellation rates that improved each month of the first quarter, leading us to anticipate relatively stronger second quarter sales results," said Steven J. Hilton, chairman and CEO of Meritage. "But these positive trends ended at the beginning of April, as demand slowed and cancellations rose. The weaker conditions we noted in April when we reported our first quarter results, continued through May. Order cancellations increased after widely-reported concerns over credit tightening and difficulties in the subprime markets, which appeared to dampen consumers' confidence and demand for homes."emphasis added

...

"In light of weaker conditions and reduced expectations, we are reviewing our operating plans for the remainder of the year, as we continue to focus on protecting our balance sheet and maximizing our flexibility through this downturn."

Housing is taking the next expected downturn. Well, expected by some, but a complete surprise to others.

NAR Cuts Housing Forecast

by Calculated Risk on 6/06/2007 11:18:00 AM

The National Association of Realtors (NAR) has cut their 2007 forecast - again. From the NAR: Home Sales Projected to Fluctuate Narrowly With a Gradual Upturn

Existing-home sales are projected to total 6.18 million in 2007.In February the NAR forecast sales would fall to 6.44 million. In April they revised their forecast to 6.34 million (a decline of 2.2% from 2006). Their new forecast is a decline of 4.6%. Still too high, but I suppose if they revise their forecast down 2% every couple of months, they might be close by the end of the year!

Also from AP: Bush Administration Lowers Its Forecast for Economic Growth This Year

Under the administration's new forecast, gross domestic product, or GDP, will grow by 2.3 percent as measured from the fourth quarter of last year to the fourth quarter of this year. That's down from a previous projection of 2.9 percent.Sorry, but it is "quite clear" that housing has not bottomed yet. Of course Lazear has never demonstrated an understanding for housing. He thought the worst was over last November:

...

"So it is just not quite clear where we are in terms of the housing market, whether it has bottomed out," Edward Lazear, chairman of the White House's Council of Economic Advisers told reporters.

"The housing market, as you know, it has been hit, I think, harder than most of us had expected. Most forecasters were expecting a slower decline. What that probably signals is that the future will not be as negative as it otherwise would have been because we've probably had much of the decline that we're expecting to have."

Edward Lazear, Q&A Nov 21, 2006, chairman of the White House's Council of Economic Advisers

Tuesday, June 05, 2007

Wells Fargo: Homebuilding's lull 'unsustainably low'

by Calculated Risk on 6/05/2007 04:37:00 PM

Jon Lansner at the O.C. Register has an excerpt from Well Fargo's economist Michael Swanson on housing: Homebuilding's lull 'unsustainably low'

In 2005, the market experienced 2.1 million housing starts, which was the highest level since 1972’s 2.4 million starts.This analysis is incorrect.

...

In 1972, US population was 210 million with 66.7 million households, and the average household contained 3.2 people. In 2007, US population is an estimated 302 million with 115.6 million households. That implies that the average number of people per household had fallen to 2.6. 2005’s peak construction doesn’t hold a candle to early rates of construction. In 1972, the market started 11.3 houses per thousand of population versus 2005’s 7 houses. And, the discrepancy in houses started per hundred households is even larger with 1972’s peak of 3.5 houses dropping to 1.8 houses. Adjusted for population and household creation, 2005’s peak wasn’t particularly impressive, and the current bottom is unsustainably low.

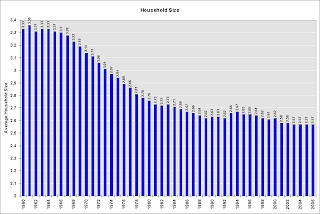

There has been a long term trend towards smaller size households in the U.S. During the '70s, there was a rapid decrease in the size of households, probably because the baby boomers were moving out on their own.

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.This graph shows household size in the U.S. (Source: Census Bureau). Note that the graph starts at 2 to better show the change.

If the population had been steady during the '70s (no growth), the U.S. would still have needed to add 9 million housing units because of the shift in household sizes. However, since 2000, if the population had stayed steady, the U.S. would have only had to add 0.4 million housing units - since the average household size has barely changed.

So, unless Dr. Swanson is suggesting there will be another significant decrease in household sizes in the near future, his analysis is apples vs. oranges. The analysis should be adjusted for changes in household size, and Dr. Swanson will discover that the recent level of starts was "unsustainable".

Dr. Swanson also picked the peak year for starts; the average in the '70s was 1.75 million units per year compared to 1.83 million since 2000. This is before adjusting for changes in household size. If we subtract 900K (9 million total per decade) per year during the '70s that gives 0.85 million starts per year. If we subtract 70K (400K total for six years) per year from the '00s that gives 1.76 million per year. Those are the numbers Swanson should be comparing to population size.

The population increased 36% (average for '70s vs. average for '00s), but starts more than doubled.

Note: On the reason for the large shift in household size during the '70s, the Census Bureau provides data on the intent of housing starts: New Privately Owned Housing Units Started in the United States, by Intent and Design. Unfortunately the data doesn't start until 1974, but it appears there were significantly larger percentage of "built to rent" units in the '70s - suggesting the Baby Boomers moving explanation might be correct.