by Calculated Risk on 4/26/2009 07:47:00 PM

Sunday, April 26, 2009

Summers: Expect "sharp declines in employment"

From Bloomberg: Summers Says U.S. Economy to Decline ‘For Some Time’

“I expect the economy will continue to decline,” with “sharp declines in employment for quite some time this year,” Summers said today on “Fox News Sunday.”Reuters has more quotes: Summers says no unremitting freefall in US economy

...

Summers said the economy will pick up as manufacturers rebuild depleted inventories and consumers replace aging cars. “These imbalances can’t continue forever,” he said. “When they are repaired they will be a source of impetus for the economy.”

...

Summers said the Obama administration is “on a path toward containment and toward building a path toward expansion,” he said, adding that “even sharp plans take time” to work, perhaps six months or more.

“Six or eight weeks ago, there were no positive statistics to be found anywhere. The economy felt like it was falling vertically. Today, the picture is much more mixed,” Summers said.The "unremitting freefall" might be ending, but what will be the source of growth? Usually residential investment (RI) and personal consumption lead the economy out of a recession - and both remain severely impaired this time. There is too much excess inventory for any meaningful recovery in RI, and the process of repairing household balance sheets has just begun (I expect the savings rate to continue to rise for some time).

“There are some negative indicators, to be sure. There are also some positive indicators. And no one knows what the next turn will be,” he said. “But I think that sense of unremitting freefall that we had a month or two ago is not present today. And that’s something we can take some encouragement from.”

Krugman spoke about this in Cincinnati:

"I'm in the camp that really worries about the L-shaped recession. We level off but we don't get the recovery. We hope it isn't, but it has all the markings of it. This looks like the kind of slump that has all the markings of where normal recovery forces are very, very weak.

It's hard to see where recovery comes from."

Bank Balance Sheet: Liquidity and Solvency, Part II

by Calculated Risk on 4/26/2009 03:26:00 PM

In the previous post, I tried to present a conceptual overview of a liquidity crisis using a bank's balance sheet: Bank Balance Sheet: Liquidity and Solvency, Part I. Note: I combined various types of financial institutions to illustrate a few points.

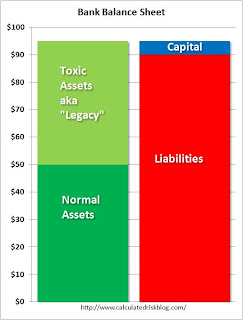

As we continue the story, the bank has suffered some losses, but the bank run has been halted by the efforts of the FDIC (increasing insurance limit), or the Fed (by providing liquidity). Click on graph for larger image in new window.

Click on graph for larger image in new window.

This time we look at the bank's assets. What I've labeled as "normal assets" are various categories of assets, perhaps commercial & industrial (C&I) loans, consumer loans, and others. Although the charge-offs are increasing for all of these loans during the recession, these assets have a market value or otherwise are in OK shape.

The larger problem is the toxic assets (now known as legacy assets). These are mostly related to residential real estate, but there are many other toxic loans (Construction & Development, foreign loans, LBO PE loans, etc.)

The banks are facing huge additional losses for these legacy assets, and these losses will make some banks "balance sheet" insolvent (liabilities will be great than assets). However, the bank is not insolvent in the business sense, because the bank can still pay their debts as they come due - at least for now.

But these future losses (even just the fear of future losses) will make it impossible for the banks to borrow or raise additional private capital. So Paulson's solution was to remove the legacy assets from the bank's balance sheet. This was the purpose of the Master Liquidity Enhancement Conduit (MLEC), the original purpose of the TARP, and even the goal of Geithner's PPIP. Basically the goal is to replace the legacy assets with money from the MLEC, TARP (original plan) or the PPIP.

Basically the goal is to replace the legacy assets with money from the MLEC, TARP (original plan) or the PPIP.

All of these programs suffer from the same problem. If they buyer's pay too little, the banks will be insolvent, and if the buyer's pay too much for the assets, this is a transfer of wealth from the buyers to the stakeholders of the banks.

The PPIP uses private buyers to set the price, but it suffers from the same problems as the MLEC and TARP (original). Because of the structure (with a non-recourse loan), the buyers can pay more than market value because they have a put option (they have minimal downside risk). This put option is a transfer of wealth from taxpayers to the stakeholders of the banks. If the PPIP buyers bid too little, the banks will reject the bid - I think this is a likely outcome. Because of pricing issues for legacy assets, the TARP was changed to inject additional capital into the banks with preferred stock.

Because of pricing issues for legacy assets, the TARP was changed to inject additional capital into the banks with preferred stock.

This additional capital provides the banks with a little more cushion to handle losses, but if the value of the legacy assets is - say - cut in half, the banks will still be balance sheet insolvent. This might help some banks, but other banks will still need additional capital.

And there is the question of what percentage of the bank should the government own with the additional capital. If the banks were seriously insolvent, why aren't the original shareholders wiped out? Once again this is a transfer of wealth from the taxpayers to the existing stakeholders.

So what is the solution? The FDIC approach (aka Preprivatization) would be to seize the bank, and wipe out the shareholders.

The FDIC approach (aka Preprivatization) would be to seize the bank, and wipe out the shareholders.

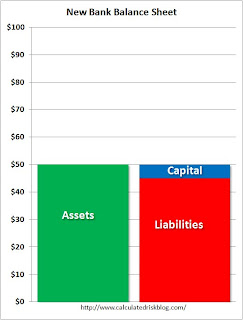

The government would take all the legacy assets and create a new Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC) like institution to dispose of the assets. The bank would be recapitalized and eventually sold to the public as a much smaller institution.

There are a range of possibilities on how to handle the debtholders. They could receive a haircut, and perhaps an interest in the RTC assets (above a certain price), and maybe an equity interest in the New Bank. Or, at the other end of the spectrum, they could be paid off in full.

This would probably depend on any systemic issues. The Geithner approach is to keep injecting capital into the banks to cover the losses. This is known as the "Zombie" bank approach.

The Geithner approach is to keep injecting capital into the banks to cover the losses. This is known as the "Zombie" bank approach.

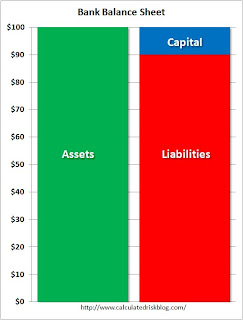

In essence the balance sheet looks like this with liabilities greater than total assets. To make the zombie balance sheet "balance", I've added "??????" to the assets.

These "??????" assets are either future retained earnings or additional money from the government. Although the bank is balance sheet insolvent, the bank will never be business insolvent because the government will continue to provide money to cover losses.

If only a small percentage of financial assets are held by zombie banks, then this approach will probably work. These banks will be crippled, but the other banks can meet the financing needs of the economy.

This is why the stress tests are so important in helping identify zombie banks - and why financial institutions relying on government support should be required to make the entire test results public. If there are too many zombies, we need to insist on preprivatization.

Bank Balance Sheet: Liquidity and Solvency, Part I

by Calculated Risk on 4/26/2009 11:57:00 AM

Note: I took some short cuts to make this simple - think of this conceptually. I'm intentionally mixing financial institutions. For commercial banks, the FDIC stopped the bank run by upping the FDIC insurance. For investment banks, the Fed provided the liquidity. Please think of this conceptually or I'll have to write 100 pages ...

This post looks at a bank balance sheet and a liquidity crisis. In a subsequent post, I'll look at a solvency crisis and two possible solutions.

A special hat tip to This American Life’s Alex Blumberg and NPR’s Adam Davidson who presents some of the same ideas (although I'm going to go further). Here is the website for their presentation. Click on graph for larger image in new window.

Click on graph for larger image in new window.

If you watch the Planet Money presentation, they explain the basics of a bank from a balance sheet perspective. It doesn't matter if the left scale is in dollars or billions of dollars - the structure is the same.

Capital is the amount of money investors put into the bank plus any retained earnings. Liabilities is the money the bank borrows from depositors or other sources. And assets are loans that the bank makes (and a little cash and other assets). (see Alex and Adam's presentation to make this clear).

The balance is: Assets = Capital + Liabilities

Banks make money by lending at a higher rate than they borrow. In the Planet Money example, the banks borrowed at 3%, loaned the money at 6%, for a spread of 3%. The difference between 6% and 3% is called the "net interest spread".

Banks report something a little different called the "net interest margin". The difference between the "spread" and the "margin" is because not all assets are loans (some might be held as cash for regulatory reasons). Net Interest Margin (NIM) is the interest earned, minus the interest paid, divided by total assets. As an example, Wells Fargo just reported a net interest margin of "approximately 4.1 percent".

Now look at how profitable a bank could be. If this bank had $100 billion in assets, and a NIM of 4.1% that would be $4.1 billion in annual profits before expenses and charge-offs - on just $10 billion in capital (Note: The diagram shows 10-to-1 leverage; many banks were levered 30-to-1 or more).

Of course the bank has expenses (all those nice buildings and employees) - and there are always charge-offs for loans that don't get repaid, even in good times. For reference, the Federal Reserve tracks the charge-offs by loan category here.

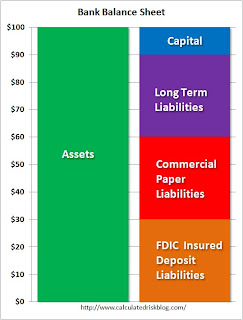

Banks have two main risks: interest rate risks and credit risks. Since banks mostly borrow short and lend long, they are exposed to increases in short term interest rates, and this would lead to lower NIMs. The credit risk is that too many of those assets will go bad (more on credit risks in the next post). Not all liabilities are the same. The second diagram shows three categories of liabilities: 1) Long term bank debt, 2) commercial paper (called CP, this is less than 270 days duration, and usually much shorter), and 3) FDIC insured deposits.

Not all liabilities are the same. The second diagram shows three categories of liabilities: 1) Long term bank debt, 2) commercial paper (called CP, this is less than 270 days duration, and usually much shorter), and 3) FDIC insured deposits.

Each category has advantages and disadvantages.

Commercial paper is usually the lowest interest rate, but it is the shortest duration and has the highest interest risk. Usually the bank pays the highest interest rate on long term debt, but there is no interest risk for the duration of the security. Most banks have a mix of liabilities.

Now imagine the bank starts reporting higher than expected credit losses - or at least depositors believe the bank will start reporting huge loses.  Here the bank has lost $5 billion, and the capital has been cut in half.

Here the bank has lost $5 billion, and the capital has been cut in half.

Fearing further losses, the commercial paper (CP) investors run for the hills and refuse to reinvest again when their short term paper matures.

The FDIC insured depositors run (or amble) towards the hills too. A classic bank run.

The long term debt holders are stuck. They can sell in the market, but at a lower price - and that doesn't impact the bank's balance sheet (OK, there are some accounting issues here that I will ignore).

To stop the bank run, the FDIC stepped up and increased the guarantee on FDIC insured assets to $250 thousand. But this did nothing for the commercial paper investors.  Next the Fed steps in and replaces the commercial paper liability as it matures.

Next the Fed steps in and replaces the commercial paper liability as it matures.

If this was just a panic, and the bank was actually fine, the commercial paper investors would return (or the bank could sell more long term debt), and the Fed would be replaced by private debt.

However this is not just a liquidity crisis, and the Fed is still providing liquidity to the banks.

This doesn't work long term because the Fed requires the banks to over collateralize any money borrowed from the Fed. As the long term debt starts to mature, those investors will follow the commercial paper investors to the hills - and the Fed will have to provide more and more liquidity. And eventually there will not be enough collateral to borrow from the Fed. Here is an example of the Collateral Margins Table for the discount window.

Next I'll discuss the solvency issues (not as easy to fix).

Krugman Worries about L-Shaped Recession

by Calculated Risk on 4/26/2009 10:15:00 AM

From the Cincinnati Enquirer: Nobel-winning economist speaks at UC (ht Jonathan)

The country may experience some economic growth in the latter half of this year, but don't expect the rate of job losses to abate anytime soon, noted economist and recent Nobel Prize laureate Paul Krugman told an audience of economists and area business leaders Friday at the University of Cincinnati.And from a separate interview with the Enquirer:

...

"There are two kinds of recessions that are bad - those that take place because of financial crises, and those that are synchronized around the world," he said. "In both cases, the recessions tend to last longer and be deeper. Right now, we've got both going on."

Q: What will it take to pull out of this crisis?

Krugman: I'm in the camp that really worries about the L-shaped recession. We level off but we don't get the recovery. We hope it isn't, but it has all the markings of it. This looks like the kind of slump that has all the markings of where normal recovery forces are very, very weak.

It's hard to see where recovery comes from. Almost always the way a country recovers from a financial crisis is with an export boom. The problem is that we have a global crisis this time. So who are we going to export to, unless we find another planet to take our stuff?

Economist: A Glimmer of Hope?

by Calculated Risk on 4/26/2009 01:15:00 AM

The Economist cover story is titled A glimmer of hope? and cautions: "The worst thing for the world economy would be to assume the worst is over" Click on cover for larger image in new window.

Click on cover for larger image in new window.

[W]elcome as it is, optimism contains two traps, one obvious, the other more subtle. The obvious trap is that confidence proves misplaced—that the glimmers of hope are misinterpreted as the beginnings of a strong recovery when all they really show is that the rate of decline is slowing. The subtler trap, particularly for politicians, is that confidence and better news create ruinous complacency. Optimism is one thing, but hubris that the world economy is returning to normal could hinder recovery and block policies to protect against a further plunge into the depths.

emphasis added

Late Night Open Thread

by Calculated Risk on 4/26/2009 12:04:00 AM

Just an open thread for discussion ... this story is concerning:

From the NY Times: Students Fall Ill in New York, and Swine Flu Is Likely Cause

Tests show that eight students at a Queens high school are likely to have contracted the human swine flu virus that has struck Mexico and a small number of other people in the United States, health officials in New York City said yesterday.

The students were among about 100 at St. Francis Preparatory School in Fresh Meadows who became sick in the last few days, said Dr. Thomas R. Frieden, New York City’s health commissioner.

“All the cases were mild, no child was hospitalized, no child was seriously ill,” Dr. Frieden said.

Saturday, April 25, 2009

Charlie Rose: Stiglitz and Ackman

by Calculated Risk on 4/25/2009 06:25:00 PM

Last night, economist Joseph Stiglitz, investor Bill Ackman (Pershing Square), and NY Times journalist Andrew Ross Sorkin discussed toxic assets with Charlie Rose. The entire discussion isn't available yet, but here is a short excerpt:

First American Economist on Housing

by Calculated Risk on 4/25/2009 02:45:00 PM

From Jon Lansner at the O.C. Register: No recovery seen for housing until late 2010. A few excerpts (not in order):

Nobody has a bigger stack of housing data than the First American real estate information empire from Santa Ana. We figured we’d ask Sam Khater, an economist at First American’s CoreLogic unit, what’s up ...It seems most economists are looking for "stabilization" in existing home sales. I've been making the argument for some time that existing home sales will probably fall further, see: Home Sales: The Distressing Gap

Lansner: Bottom this year?

Sam: I think, absolutely, there first chance for any kind of housing recovery is late 2010. We’ll see some bumps from the stimulus and the economy will look somewhat better than it really is. But we won’t see any housing bottom — and I’m talking prices — until late 2010. To me, the price is the most important thing.

...

Lansner: We seem to be enjoying a sales bump recently …

Sam: ... What you’re seeing in California is an uptick in distressed sales. All things being equal, the distressed sales will eventually wear off and sales will slow again.

... We have to remember what a normal year us. We’re not that far below, in terms of sales. You’ve got to view some of these housing numbers through a long-term series.

emphasis added

And here is a long term graph:

Click on graph for larger image in new window.

Click on graph for larger image in new window.This graph shows existing home turnover as a percent of owner occupied units. Sales for 2009 are estimated at the March rate of 4.57 million units.

I've also included inventory as a percent of owner occupied units (all year-end inventory, except 2009 is for March).

The turnover rate is just below the median of the last 40 years - and will probably fall further in coming years.

Also - notice when Khater is talking a housing "bottom" he makes it clear he is talking prices. There are typically two bottoms for a housing bust - the first is for residential investment (new home sales, housing starts, etc.) and the second - usually much later - is for existing home prices.

The Pain in Spain and in Britain

by Calculated Risk on 4/25/2009 08:55:00 AM

From The Times: Spain's unemployment rate leaps to record high

According to the country's National Statistics Institute a record high figure of 17.4 per cent were unemployed in the first quarter of the year.And in Britain, from the Telegraph: British economy shrinks at fastest pace for 30 years during first quarter of 2009

Unemployment leapt from 13.9 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2008, the biggest quarterly jump since 1976. Joblessness in Spain has almost doubled in a year.

...

Dominic Bryant, an economist with BNP Paribas, said: “The momentum is clearly there for something well above 20 per cent, it's odds on, really. My forecast is that it gets to something around about 23 per cent.”

Gross domestic product (GDP) fell by 1.9pc in the first quarter ... a sharper decline than the 1.6pc fall in the final quarter of 2008 when Britain officially entered recession.In the U.S. the headline GDP number is the real (inflation adjusted) quarterly change, seasonally adjusted at an annual rate (SAAR). In Britain and the EU, the headline GDP number is the real quarterly change, but it is not the annual rate. So a 1.9% decline in the U.K. is about the same as a 7.6% decline (SAAR) in the U.S. Ouch!

It was the sharpest quarterly fall in GDP since 1979, when it fell by 2.4pc in the third quarter.

Friday, April 24, 2009

Fed's White Paper: More Should be Released

by Calculated Risk on 4/24/2009 10:04:00 PM

Note to the Fed: Clearly some analysts have the 12 categories and related indicative loss rates. To be fair, the Fed should release this additional information ASAP.

A few analyst quotes via Bloomberg: Rosner, Davis, Investors Comment on Fed Model for Stress Tests

“The anticipation over the white paper appears to be much ado about nothing. The most significant numbers provided by the Fed in the paper appear to be the page numbers.”Each analyst makes a key point.

Josh Rosner, an analyst at Graham Fisher & Co. in New York.

“[C]ompletely worthless. We were looking for the translation of the economic forecasts to loan losses and we didn’t get that.”

David Trone, an analyst at Fox-Pitt Kelton Cochran Caronia.

“The assumptions the regulators have used here seem to imply that they’re anticipating a bottoming out of the economic downturn. The momentum in the economy might potentially make the alternative more adverse scenario the baseline scenario.”

Jeff Davis, director of research at Howe Barnes Hoefer & Arnett in Chicago.

I think the only interesting number in the white paper was "12"; the Fed noted that the banks were "instructed to project losses for 12 separate categories of loans".

Based on how the Fed reports Charge-off and Delinquency Rates, we can guess the 12 categories (Update: these are listed in the appendix):

As David Trone noted, why didn't the Fed provide the "translation of the economic forecasts to loan losses"? The Fed noted that the banks "were provided with a range of indicative two‐year cumulative loss rates for each of the 12 loan categories for the baseline and more adverse scenarios." Why not provide these indicative loss rates?

Heck, the WSJ has leaked some of these loss rates:

The Wall Street Journal released details of a confidential document that the Federal Reserve gave banks in February. The document provided details about the formulas regulators used to assess loan losses in a worsening economic environment.

...

One scenario that assumed a 10.3% unemployment rate at the end of 2010 required banks to calculate two-year cumulative losses of 8.5% on mortgage portfolios, 11% on home-equity lines of credit, 8% on commercial and industrial loans, 12% on commercial real-estate loans and 20% on credit-card portfolios.

Click on graph for larger image in new window.

Click on graph for larger image in new window.Under those assumptions, 13 of the banks undergoing the stress tests could be hit with $240 billion of losses, according to Westwood Capital LLC.Clearly Westwood Capital has the indicative loss rates - doesn't that create an unfair playing field that some people have the information and others do not?

And finally, as Jeff Davis noted (and I've been writing for some time), the "more adverse" scenario is the new baseline.