by Calculated Risk on 10/31/2007 04:15:00 PM

Wednesday, October 31, 2007

On Estimating PCE Growth for Q3

Each quarter I've been estimating PCE growth based on the Two Month method. Once again, this method has provided a very close estimate for the actual PCE growth.

Some background: The BEA releases Personal Consumption Expenditures monthly (as part of the Personal Income and Outlays report) and quarterly, as part of the GDP report (also released separately quarterly).

You can use the monthly series to exactly calculate the quarterly change in PCE. The quarterly change is not calculated as the change from the last month of one quarter to the last month of the next (several people have asked me about this). Instead, you have to average all three months of a quarter, and then take the change from the average of the three months of the preceding quarter.

So, for Q3, you would average PCE for July, August and September, then divide by the average for April, May and June. Of course you need to take this to the fourth power (for the annual rate) and subtract one.

The September data isn't released until after the advance Q3 GDP report. But I used the change from April to July, and the change from May to August (the Two Month Estimate) to approximate PCE growth for Q3. Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

This graph shows the two month estimate versus the actual change in real PCE. The correlation is high (0.92).

The two month estimate suggested real PCE growth in Q3 would be about 3.0%. The actual result (in the Advance GDP report) was also 3.0%.

Since the two month estimate was very accurate, this suggests that there was little slowdown in consumer spending in September.

As an aside, the Fed now has the results (not public yet) of the October Senior Loan Officer survey. Based on the Fed statement today, I bet the numbers are ugly.

Fed Cuts Rates, Says Economy to Slow

by Calculated Risk on 10/31/2007 02:13:00 PM

Fed Statement:

The Federal Open Market Committee decided today to lower its target for the federal funds rate 25 basis points to 4-1/2 percent.

Economic growth was solid in the third quarter, and strains in financial markets have eased somewhat on balance. However, the pace of economic expansion will likely slow in the near term, partly reflecting the intensification of the housing correction. Today’s action, combined with the policy action taken in September, should help forestall some of the adverse effects on the broader economy that might otherwise arise from the disruptions in financial markets and promote moderate growth over time.

Readings on core inflation have improved modestly this year, but recent increases in energy and commodity prices, among other factors, may put renewed upward pressure on inflation. In this context, the Committee judges that some inflation risks remain, and it will continue to monitor inflation developments carefully.

The Committee judges that, after this action, the upside risks to inflation roughly balance the downside risks to growth. The Committee will continue to assess the effects of financial and other developments on economic prospects and will act as needed to foster price stability and sustainable economic growth.

Voting for the FOMC monetary policy action were: Ben S. Bernanke, Chairman; Timothy F. Geithner, Vice Chairman; Charles L. Evans; Donald L. Kohn; Randall S. Kroszner;

Frederic S. Mishkin; William Poole; Eric S. Rosengren; and Kevin M. Warsh. Voting against was Thomas M. Hoenig, who preferred no change in the federal funds rate at this meeting.

In a related action, the Board of Governors unanimously approved a 25-basis-point decrease in the discount rate to 5 percent. In taking this action, the Board approved the requests submitted by the Boards of Directors of the Federal Reserve Banks of New York, Richmond, Atlanta, Chicago, St. Louis, and San Francisco.

Moody's: D.R. Horton, Ryland May be Cut to "Junk"

by Calculated Risk on 10/31/2007 12:59:00 PM

From Reuters: Moody's may cut D.R. Horton, Ryland, into junk

Moody's ... said it may cut its ratings on D.R. Horton Inc and Ryland Group Inc into junk territory ...

The builders have struggled to generate free cash flow, "in part because of their limited success to date in reducing actual inventory, in part because of continuing high cancellation rates, and in part because of the fiercely competitive environment the two companies face in most of their markets," Moody's said in a statement.

"Exacerbating the situation, especially in the case of Horton, is the elevated level of (speculative) inventory," Moody's said.

Q3 Structure Investment

by Calculated Risk on 10/31/2007 11:34:00 AM

According to the BEA, Residential Investment declined at a 20.1% annual rate in Q3 2007.

The first graph shows Residential Investment (RI) as a percent of GDP since 1960. Click on graph for larger image

Click on graph for larger image

Residential investment, as a percent of GDP, has fallen to 4.51% in Q3 2007, and is now below the median for the last 50 years of 4.56%.

Although RI has fallen significantly from the cycle peak in 2005 (6.3% of GDP in Q3 2005), RI as a percent of GDP is still well above all the significant troughs of the last 50 year (all below 4% of GDP). Based on these past declines, RI as a percent of GDP could still decline significantly over the next year or so.

The fundamentals of supply and demand also suggest further significant declines in RI.

Non Residential Structures Investment in non-residential structures continues to be very strong, increasing at a 12.3% annualized rate in Q3 2007.

Investment in non-residential structures continues to be very strong, increasing at a 12.3% annualized rate in Q3 2007.

Investment in non-residential structures is now 3.44% of GDP, above the recent peak in 2001. Whereas RI declines prior to a recession, non-residential investment in structures tends to peak during a recession.

Accounting For Negative Amortization

by Tanta on 10/31/2007 10:00:00 AM

Accounting for negative amortization is a perennial favorite amongst those who follow banks and thrifts with large Option ARM portfolios. It outrages a lot of folks that the neg am balances, which represent interest that has been earned but not paid, is considered noncash interest income. It also seems to outrage a lot of folks that OA portfolio holders do not simply declare these capitalized balances as "uncollectable." The idea seems to be that 1) the fact of negative amortization itself should mean that the loan is substandard or doubtful, regardless of timely payment of the contractually allowed minimum payment, and therefore 2) the accounting treatment for reserve purposes should be the much more onerous one, "all estimated credit losses over the remaining effective lives of these loans," rather than the standard for non-classified loans, "all estimated credit losses over the upcoming 12 months."

I think this is the argument Jonathan Weil is trying to make in this piece on WaMu:

As for the fourth quarter, Washington Mutual predicted that provisions would be $1.1 billion to $1.3 billion and that charge-offs would increase 20 percent to 40 percent.If you have any sense of how the OA market worked in the last three or four years, you have to find Weil's approach here a bit odd. Back in 2004-2005, when WaMu had more OAs on its books, it had younger OAs on its books. It takes some time for OAs to build up neg am balances, and as origination of this product really didn't take off until 2003-2004, you wouldn't expect any portfolio of OAs to have large capitalized balances for at least a few years.

To see why even $1.3 billion in provisions looks light, consider Washington Mutual's $57.86 billion of so-called option- ARM loans, which make up 24 percent of Washington Mutual's loan portfolio. These adjustable-rate mortgages were popular during the housing bubble, because they give customers the option of postponing interest payments, which the lender then adds to their principal balances.

As of Sept. 30, the unpaid principal balance on Washington Mutual's option ARMs exceeded the loans' original principal amount by $1.5 billion, meaning the customers owed $1.5 billion more in principal than what they originally borrowed. By comparison, that figure was $681 million a year earlier, when Washington Mutual had $67.14 billion, or 16 percent more, option ARMs on its books.

Look to the end of 2005, and the trend becomes even starker. Back then, Washington Mutual had even more option ARMs on its balance sheet, at $71.2 billion. Yet the unpaid principal balance exceeded the original principal amount by only $160 million -- and that was up from a mere $11 million at the end of 2004.

Deferring Pain

The deferred interest from option ARMs also boosts Washington Mutual's earnings, part of a process known as negative amortization, or ``neg-am.'' That's because option-ARM lenders recognize interest income when customers postpone their interest payments, even though the lenders got no cash.

For the nine months ended Sept. 30, Washington Mutual recognized $1.05 billion in earnings as a result of neg-am within its option-ARM portfolio. That represented 7.2 percent of Washington Mutual's $14.61 billion of total interest income year-to-date. By comparison, neg-am contributed 1.8 percent of Washington Mutual's interest income for all of 2005 and just 0.2 percent for 2004.

What's going on here? Either the borrowers postponing their interest payments are doing so as a matter of choice, by and large, or they can't afford to pay them. Common sense suggests it's the latter -- and that there's serious doubt Washington Mutual ever will collect the $1.5 billion of postponed interest that its option-ARM customers have added to their original principal balances.

What Weil is doing is trying to find a negative trend in the performance of these loans: his "common sense" says that the very fact of negative amortization means the borrowers are in trouble, and the very fact that neg am balances are growing in WaMu's portfolio means that a reasonable person would assume that this pattern should be projected into the foreseeable future. What that implies, of course, is that WaMu should "classify" all of these loans, regardless of LTV, timely payment, etc., on the recognized accounting basis of the "negative trend." If they did that, they would have to reserve a lot more against these loans, since allowances for classified loans are required, by the OTS, to be for the life of the loan. Reserves for nonclassified loans are for the next twelve months.

Yet the $1.1 billion to $1.3 billion of fourth-quarter provisions that Washington Mutual predicted -- for the company as a whole -- wouldn't even cover the $1.5 billion of tacked-on principal. The trend among Washington Mutual's option ARMs shows no sign of slowing, either.Surely not even the greatest OA skeptic believes that WaMu could conceivably face default of every last one of its OAs with a neg am balance in the next 12 months. Without saying so explicitly, Weil is suggesting that WaMu pack lifetime estimated losses on this portfolio into current reserves, for no other reason than that the loans are negatively amortizing.

Through a spokeswoman, Libby Hutchinson, Washington Mutual officials declined to comment. She said the company's executives aren't fielding questions until their next meeting with investors on Nov. 7.

Then there's the bigger picture. While Washington Mutual's loan-loss allowance rose 22 percent to $1.89 billion during the 12 months ended Sept. 30, nonperforming assets rose 128 percent to $5.45 billion. So even if Washington Mutual adds $1.3 billion in provisions next quarter, its loan-loss allowance still won't be anywhere close to catching up.

To be sure, Washington Mutual executives have some latitude over the timing of the company's loan-loss provisions. Yet they also may have a monetary incentive to push losses into 2008.

To me, that is the crux of all of this upset over OA accounting. I personally would not make OAs nor would I hold them in any portfolio over which I had control, so don't think I'm defending the product. However, we just went through a major regulatory effort on "nontraditional mortgage products," and the upshot of that was that the regulators did not and would not deem the negative amortization ARM an unacceptable product for depositories, in and of itself. There is plenty in the Nontraditional Mortgage Guidance about what underwriting practices and so on should be followed with these loans, and certainly the guidance isn't a carte blanche for writing any old dumb OA an institution can think of. But they are not, explicitly, "classified" just because they're OAs:

When establishing an appropriate ALLL and considering the adequacy of capital, institutions should segment their nontraditional mortgage loan portfolios into pools with similar credit risk characteristics. The basic segments typically include collateral and loan characteristics, geographic concentrations, and borrower qualifying attributes. Segments could also differentiate loans by payment and portfolio characteristics, such as loans on which borrowers usually make only minimum payments, mortgages with existing balances above original balances, and mortgages subject to sizable payment shock. The objective is to identify credit quality indicators that affect collectibility for ALLL measurement purposes.I do not know how to read this except that there must be specific indicators of credit quality in the analysis besides the fact that the loans are "nontraditional" and that the issue is capital adequacy, not just reserves (capital being expected to cover long-horizon potential losses, and reserves being expected to, well, cover the short term). Weil's "common sense" may tell him that neg am = loan distress by definition, but the regulators' common sense didn't tell them that, and whose common sense do you think matters to WaMu?

What this means is that the federal regulators have said that the fact that a loan accrues neg am balances does not, in and of itself, make the loan unacceptable, substandard, or uncollectable. How, precisely, banks are supposed to get away with reserving for them as if they were beats me: the regulators can get on your case just as much for over-reserving as for under-reserving, as this can smack of "cookie jar" accounting. The only way a bank could defend itself against the charge of over-reserving would be for it to define OAs as unacceptable as a product, without regard to any other facts or characteristics. Why does Weil or anyone else expect an originator of OAs to do this?

Similarly with the issue of treating neg am as income: what else would you treat it as? To argue that deferred interest is never in fact collectable is to argue that OAs always default and the recovery is never enough to cover the balance due. If you believed that to be true, you would never make such loans.

And the issue of a "trend" suffers from the same problems. OAs allow for negative amortization up to some limit. That is established in the legal documents when the loan is closed. When you make those loans, you must assume that any and all borrowers may elect to make the minimum payment. That means that a "trend" over time will occur in a highly predictable way, known as an "amortization schedule." Certainly some industry participants have expressed some pearl-clutching surprise over the fact that making the minimum payment seems to be near-universal among outstanding OA loans, but we can file that under the "stunned but not surprised" heading. You do not make neg am loans unless you're prepared for neg am.

The point: the accounting treatment for these loans--reserves, asset classification, income--isn't going to change as long as they're "legal." And nobody is going to reserve for an OA portfolio today assuming that it will be a total loss in the next twelve months. And nobody is going to stop treating accrued but unpaid interest as income. If you have problems with that--and you surely might--then what you have problems with is allowing banks and thrifts to originate and hold these loans tout court, because you have implicitly defined them as substandard to the extent that they do what they are designed to do.

I realize that it is, in some quarters, more entertaining to speculate about accounting shenannigans than it is to face up to the implications of your rhetoric, but there it is. If you want OAs to be illegal, say so, and let me know what happens when the free-marketers jump all over your case. Otherwise, this business of implying that WaMu is reserving against its performing OA portfolio only for losses expected in the next twelve months because it's playing bonus games, not because that's what the reserve rules are, is really disingenuous.

One can make the case that it is simply impossible to accurately treat a portfolio of OAs: they're either always under-reserved or always over-reserved. Fine. I have some sympathy with that argument. But it's an argument for the abolition of OAs, not a criticism of any one bank's application of accounting rules. In any case, I challenge anyone who has a problem with WaMu's accounting for its OA portfolio, but who does not think the product should be outlawed, to explain to me what it is you do want.

Q3 GDP Growth: 3.9 Percent

by Calculated Risk on 10/31/2007 09:25:00 AM

From the WSJ: GDP Grew 3.9% in Third Quarter On Exports, Consumer Spending

Gross domestic product rose at a seasonally adjusted 3.9% annual rate in the third quarter, the Commerce Department said Wednesday in its first estimate of growth for the July-September period. GDP climbed at a 3.8% pace in the second quarter and 0.6% in the first.Also ADP reports: ADP Numbers Show Job Market Improvement

ADP said nonfarm private employment increased 106,000 in October, following three months in which private-sector jobs grew by an average of 43,000 a month. Assuming public employment rose by 19,000 — the average monthly gain over the last year — the ADP numbers imply that Friday’s payroll report from the Labor Department will show an increase of 125,000 in total nonfarm employment.I'll have more on investment later.

Tuesday, October 30, 2007

Fed Rate Decision

by Calculated Risk on 10/30/2007 09:56:00 PM

Dr. Tim Duy writes at Economist's View: Fed Watch: And So It Begins

"The Fed begins a two-day meeting today, with market participants widely expecting a rate cut. I am mentally prepared to be on the wrong side of this call, joining the lonely few, but I just can’t tease another rate cut out of the incoming data."This is another excellent overview from Tim Duy. Recommended reading!

And Tim makes a point I've been thinking about all day:

"... if they do cut, I wish they would stop telling us that their forecast is for moderate growth near potential. A rate cut would suggest that they clearly do no[t] believe that forecast."Exactly.

In addition to the data that Tim cites, add in this story from the WSJ: P&G, Colgate Plan to Increase Prices

Pressured by high commodity costs, Procter & Gamble Co. and Colgate-Palmolive Co. said they would raise prices on consumer staples .... P&G's price increases will be particularly extensive, between 3% and 12% on goods including diapers, fabric softener and pet food.That suggests P&G and Colgate have significant pricing power. A rate cut with rising prices and a moderate growth forecast? Who's the Fed Chief? Arthur Burns?

Housing Busts and Sticky Prices

by Calculated Risk on 10/30/2007 06:00:00 PM

Even though the current housing bubble is probably the largest ever, both in price terms (relative to fundamentals) and geographically (the bubble was widespread), the bust is still following the normal pattern.

A typical housing bubble does not "pop", rather prices decline slowly, in real terms, over several years. This is because house prices display strong persistence and are sticky downward. Sellers tend to want a price close to recent sales in their neighborhood, and buyers, sensing prices are declining, will wait for even lower prices.

This means real estate markets do not clear immediately, and what we initially observe is a drop in transaction volumes, followed some time later by price declines. We are now observing price declines, with the Case-Shiller index indicating that U.S. home prices have fallen 4.5% over the last 12 months.

For how long will prices decline? Although we can draw some lessons from previous housing busts, we have to remember that different areas will experience different price declines.  Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

This graph shows the Case-Shiller price indices for several selected cities. This includes some of the more bubbly areas like Miami, San Diego and Las Vegas, and other areas with less of an increase in price (like Cleveland and Denver). In general, those areas with the largest price increases will probably also experience the largest price declines.

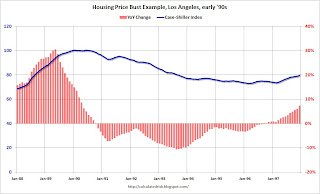

Each housing bust is somewhat unique, however prices declined for 5 to 7 years during most of the previous significant busts. We can use Los Angeles in the early '90s as an example of what happens to prices during a bust.

The second graphs show the Case-Shiller price index for Los Angeles from the late '80s until prices bottomed in 1996. The year-over-year change in prices is also shown.

Prices are sticky but not stuck. As a housing bubble peaks, appreciation slows at first (also transaction volumes decline and inventory rises - not shown), then prices start to decline. Then, about a year or so after the price peaks, prices really start to decline for a couple of years, followed by a couple more years of modest declines.

This graph is for nominal prices, in real terms prices declined almost 39% in LA during the early '90s bust. The third graph lines up the peak for the early '90s LA housing bust with the current nationwide U.S. housing peak. Using the previous bust as a guide - and with prices peaking about 15 months ago - the U.S. has probably just entered the two year period with the most severe price declines.

The third graph lines up the peak for the early '90s LA housing bust with the current nationwide U.S. housing peak. Using the previous bust as a guide - and with prices peaking about 15 months ago - the U.S. has probably just entered the two year period with the most severe price declines.

That is my expectation: we will see the most significant price declines for this cycle over the next two years, followed by more modest declines for a couple more years in the more bubbly areas.

Case-Shiller: Price Declines Accelerate in August

by Calculated Risk on 10/30/2007 11:17:00 AM

The S&P Case-Shiller Home Price index was released this morning for August 2007. The index showed that home price declines accelerated in August, with U.S. prices declining 4.5% over the last 12 months, and at a 8.5% annual rate in August.

Ora Pro Nobis Peccatoribus

by Tanta on 10/30/2007 11:00:00 AM

Now and in the close of our escrow, amen.

How desperate are home sellers getting?

Item 1: Jewish Buddhist seller buries St. Joseph in the backyard. (Money quote: "I wasn't sure if it would be disrespectful for me, a Jewish Buddhist, to co-opt this saint for my real-estate purposes," says Ms. Luna, a writer. She figured, "Well, could it hurt?")

Item 2: Mortgage broker offers a deal to die for. (Money quote: "'Holy mackerel! This is unbelievable,'" Mr. Cook said.")