by Calculated Risk on 6/03/2007 07:32:00 PM

Sunday, June 03, 2007

Housing Update, June 2007

Here are a few simple facts:

• Housing inventories are at record levels, in both absolute terms, and as a percent of owner occupied units.

• Households are already dedicating a record percentage of their income to mortgage obligations.

• Banks are tightening mortgage-lending standards.

So what will happen to the housing market? For normal markets, these facts - excess supply, falling demand - would foreshadow falling prices. But, for housing, prices are sticky because sellers tend to want a price close to recent sales in their neighborhood, and buyers, sensing prices are declining, will wait for even lower prices.

But sticky doesn't mean stuck. Prices are now falling by most measures, and will probably continue to fall. However, in a typical housing bust, prices tend to fall slowly over several years - so buyers wait, and transaction volumes also decline.

Writing in the NY Times, Floyd Norris does an excellent job of discussing the dynamics of a housing bust: The Long Life Span of a Housing Downturn (See article for more graphics).

If the current bust follows the '89 pattern, prices will decline in the index cities for another 3 years. However, the recent boom was far greater than the late '80s boom, and this bust might also be worse. Some of the hardest hit markets following the '89 bust were Los Angeles and Hartford; prices declined in both markets for more than 6 years, and the total price declines were 21% and 15% respectively in nominal terms.

One thing that was very different at the 1989 peak from the one in 2006 was the trend in the number of homes being offered for sale. When prices peaked in 1989, the number of homes for sale was already declining, and it continued to fall for some months, perhaps reflecting decisions by homeowners to hold on and wait for prices to come back.

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.This graph shows sales and inventory normalized by the number of owner occupied units. As Norris noted, inventory was flat or falling in '89, but inventory is increasing rapidly and is at an all time high.

Note: all data is year-end except 2007. For 2007, the April sales rate and inventory are used. For owner occupied units, Q1 2007 data from the Census Bureau housing survey was used for April 2007.

NOTE: In the article, Norris mentions that inventories are at record levels, but his numbers are incorrect. He wrote:

... the latest report shows that more than 4.1 million homes were for sale at the end of April, the largest number ever. That included almost 3.6 million existing homes, also a record high.Actually the total is 4.7 million with 4.2 million existing homes for sale. From the NAR:

Total housing inventory rose 10.4 percent at the end of April to 4.20 million existing homes available for sale ...Another stark difference between '89 and today is that transaction volumes are still near record highs as a percent of owner occupied units. In '89, sales had already fallen below the normal turnover level - meaning sales probably wouldn't fall much more. In the near future, it is very likely that the turnover rate for existing homes will fall back to more normal levels, putting even more pressure on prices.

In '91, the months of supply peaked at 8.1 months (end of '91, some months were higher), and currently the months of supply is already at 8.4 months. If turnover falls back to normal levels, there might be a full year or more of supply on the market.

On to the homebuilders:

Existing homes are a competing product for new homes, so for the homebuilders, all this inventory spells P-A-I-N. There is a substantial amount of excess inventory on the market - my estimate was 1.1 to 1.4 million units - Gary Shilling's estimate was over 2 million units.

So far the homebuilders have only cut starts back to about 1.5 million units (Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rate, SAAR).

So far the homebuilders have only cut starts back to about 1.5 million units (Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rate, SAAR).Back in January, Fannie Mae chief economist David Berson wrote:

We have argued for some time that the surge in housing demand in recent years ... was unsustainable. Understandably, builders responded to this pickup in overall housing demand by significantly increasing house construction. As a result, too many housing units were built in recent years relative to the underlying pace of housing demand-- bringing unsold inventories up to record highs. But how large is this overhang relative to long-term housing demand?Berson calculated the overhang at 600K (this appears to be far too low based on Census Bureau vacancy rates). Berson used 1.8 Million units per year as a steady state demand; I used 1.7 million units. This number is important, because if the builders are still starting 1.5 million units per year, and the overhang is say 1 million units (just an example, probably too low), then it will take 5 years to work off the excess inventory.

To work off the excess inventory in just a couple of years, housing starts need to fall much further - perhaps to about 1.1 million SAAR. However the builders find themselves with serious cash flow problems. They have too much land (remember the ludicrous "land bank" comments from a couple of years ago?), but they can't sell the land. Hovanian just noted:

[Land sales have] "just really slowed to a complete trickle with very few buyers of any type out there"So the builders have to build spec houses, and then discount the prices to get any money for their land. This keeps the inventory levels high and prolongs the housing slump.

In conclusion, the outlook for housing remains dismal.

Economics: The Stories We Tell Ourselves

by Anonymous on 6/03/2007 06:04:00 AM

Being a former Lit Major with an occupational interest in Economics, I was fascinated by this interview with Robert Frank, Professor of Economics at Cornell and a co-author of our Ben Bernanke's. Professor Frank is a fan of throttling back on all those graphs and equations in the teaching of introductory economics, in favor of a bit of storytelling:

The narrative theory of learning now tells us that information gets into the brain a lot more easily in some forms than others. You can get information into the student’s brain in the form of equations and graphs, yes, but it’s a lot of work to do that. If you can wrap the same ideas around stories, around narratives, they seem to slide into the brain without any effort at all. After all, we evolved as storytellers; that’s what we’re good at. That’s how we always exchanged ideas and information. And if a narrative has an actor, a plot, if it makes sense, then the brain stores it quite easily; you can pull it up for further processing without any effort; you can repeat the story to others. Those seem to be the steps that really make for active learning in the brain. [Emphasis added]

One gathers that the good professor has never read The Sound and the Fury. Or any given day's edition of the New York Times or the Washington Post or the Podunk Startlegram, wherein easily-grasped storylines--Evil Bank Forecloses On Piteous Family, Stupid Borrower Fails to Read Fine Print, Young Family Achieves Wealth Through Homeownership, Sinister Accountants Re-enact Enron Saga--do have a tendency to substitute for those graphs and equations, but not everyone is convinced we're the wiser for it. In fact, it seems as if Dr. Frank is entirely innocent of the role narratives play in ideology and propaganda, something the Lit crowd has been aware of for some time and that surely one of Dr. Frank's colleagues at Cornell's English Department might have warned him about.

I am not trying to make the tedious point about anecdotes and data, nor am I suggesting that Frank makes that mistake. I'm wondering how anyone as sophisticated as Frank can miss the distinction between plot and point of view, which, forgive me, is covered in Lit 101 as often as "opportunity cost" is covered in Econ 101. Here's an example of Frank's "economic naturalist" theory of storytelling in action:

So, for example, Bill Tjoa, one of my students in 1997, asked, Why do the keypads in the drive-up ATM machines have Braille dots on them? It’s a good question. Drivers obviously can see; why do they need Braille dots on the drive-up cash machines? Mr. Tjoa made use of the cost-benefit principle. That’s probably the simplest and most important of all of the ideas we try to stress in the course. It says that if the benefit exceeds the cost, then it’s a good idea. What he argued was that you’re going to make the machines with Braille dots on the keypads anyway for the walk-up machines, so you’ve got to incur the expense of designing and manufacturing the keypads with the Braille dots. Once you’ve done that, it’s just cheaper to make all of the machines the same way, rather than keep two separate inventories and make sure that the right machines go out to the right destinations. So: Cost lower, benefit the same, it doesn’t inconvenience drivers any to use the machines with the Braille dots, so it would be foolish to do it any other way. So the real question isn’t why should there be Braille dots on the keypads — why shouldn’t there be? There’s no reason not to put them there.

Now, I have worked for banks, so I've gotten that question a lot over the years. It never arises, at least in my experience, as the sort of thoughtful, normal-human-mind-struggles-with-economic-concepts question like "Why couldn't we just print more money? What is money, anyway?" No, it comes out in a rather different tone, more the "gotcha" thing, not a question that is hard to answer but a rhetorical question that is designed to answer itself: "boy are those banks dumb" being the approximate burden of wisdom of the exercise.

I confess it has always floored me. "Well," I say, looking as kindly and thoughtful as I can manage, "you are assuming that no one uses the drive-up lanes except drivers." Well, yeah, har, har, who else uses the drive-up lane, hikers? "Well," I say, "there are passengers, you see." Silence. "And we always counsel our blind customers not to give their PIN to the cabbie." Silence. "Of course, we could force them to make the cab wait--meter running--while they walk in to use the teller window, but it seems so unfair to do that when you can put Braille plates on the ATMs and the cannister console." Silence.

But I am not an economist, and so it never occurred to me to accept the hidden assumption that the drive-up is only for drivers. Of course it's hard to argue with Frank's assertion that "there's no reason not to put them there." So it's an extremely inexpensive way of allowing the drive-up to be useful to blind passengers in a car, apparently, because per Frank the purpose was merely to save costs on machine production while not inconveniencing drivers.

The thing is that it does seem to "inconvenience" them. It just bugs people that those Braille dots are there. It bugs them so much that the question finally got the attention of an economist, who immediately understood the question in the way that drives me nuts about economists, they never having read The Sound and the Fury, and hence never showing a lot of willingness to imagine that there is an alternative point of view that can wreak havoc with our comfortable storylines if we are willing to let it. Not everyone is behind the wheel. Sometimes it is worth the effort to challenge the stories everyone repeats. It appears that in certain contexts this is a revolutionary thought. Oh, my.

We Lit types may very well be soft-hearted and fanciful, but you Econ types are still dismal.

Saturday, June 02, 2007

Saturday Rock Blogging: In Your Pension, Your Peaceful Pension . . .

by Anonymous on 6/02/2007 12:47:00 PM

Might as well laugh . . .

Reelin' In the Suckers

by Anonymous on 6/02/2007 10:26:00 AM

In case you missed it in the comments, there were many discussions of this (excellent) Bloomberg piece yesterday, "Banks Sell 'Toxic Waste' CDOs to Calpers, Texas Teachers Fund." Please read the whole thing if you have not done so already. Some highlights:

June 1 (Bloomberg) -- Bear Stearns Cos., the fifth-largest U.S. securities firm, is hawking the riskiest portions of collateralized debt obligations to public pension funds.

At a sales presentation of the bank's CDOs to 50 public pension fund managers in a Las Vegas hotel ballroom, Jean Fleischhacker, Bear Stearns senior managing director, tells fund managers they can get a 20 percent annual return from the bottom level of a CDO. . . .

The California Public Employees' Retirement System, the nation's largest public pension fund, has invested $140 million in such unrated CDO portions, according to data Calpers provided in response to a public records request. Citigroup Inc., the largest U.S. bank, sold the tranches to Calpers.

``I have trouble understanding public pension funds' delving into equity tranches, unless they know something the market doesn't know,'' says Edward Altman, director of the Fixed Income and Credit Markets program at New York University's Salomon Center for the Study of Financial Institutions.

``That's obviously a very risky play,'' he says. ``If there's a meltdown, which I expect, it will hit those tranches first.''

Calpers spokesman Clark McKinley declined to comment. . . .

Chriss Street, treasurer of Orange County, California, the fifth-most-populous county in the U.S., says no public fund should invest in equity tranches. He says fund managers are ignoring their fiduciary responsibilities by placing even 1 percent of pension assets into the riskiest portion of a CDO.

``It's grossly inappropriate to take this level of risk,'' he says. ``Fund managers wanted the high yield, so Wall Street sold it to them. The beauty of Wall Street is they put lipstick on a pig.'' . . .

The General Retirement System of Detroit holds three equity tranches it bought for $38.8 million. The Teachers Retirement System of Texas owns $62.8 million of them. The Missouri State Employees' Retirement System owns a $25 million equity tranche.

Ronald Zajac, spokesman for the Detroit pension fund, declined to comment on the fund's equity tranche investments.

Kay Chippeaux, fixed-income portfolio manager of the New Mexico council, says it decided to buy equity tranches after listening to pitches from Merrill Lynch & Co., Wachovia Corp. and Bear Stearns.

``We got very interested in them just because a broker brought them to our attention,'' Chippeaux, 50, says. She says the investment is worth the risk because the fund may be able to get higher returns than it can from bonds. The council has purchased equity tranches from Bear Stearns, Citigroup, Merrill Lynch and Morgan Stanley.

The council is relying on advice from bankers who are selling the CDOs, Chippeaux says. ``We manage risk through who we invest with,'' she says. ``I don't have a lot of control over individual pieces of the subprime.'' . . .

Pension fund managers face the same hurdle as all CDO investors: The market has almost no transparency, with both current prices and contents of CDOs almost impossible to find, says Frank Partnoy, a former debt trader who's now a law professor at the University of San Diego.

The murky nature of the CDO market presents danger for the unwary investor, and it's particularly unsuitable for public pension money, Partnoy says.

``I think `smoke and mirrors' in some sense understates the problem,'' he says. ``You can see through smoke. You can see something reflected in a mirror. But when you look at the CDO market, you really can't see enough information to enable you to make a rational investment decision.''

That hasn't stopped pension funds from taking high risks with the retirement plans of teachers, firefighters and police. [boldface added, only because I don't have an html tag for flashing red lights]

Your pension fund managers are buying "high yield" bonds that put you in first loss position on a bunch of junk bonds, and they are doing so on the risk-management "advice" of the people who are making a commission from selling those bonds.

Look, CDOs are complicated, and one of these days I'll manage to do a long UberNerd post on them. Here's the short version, with a nice picture (vandalized by Tanta) courtesy of Pershing Capital Management:

You take a bunch of subprime loans, and make a pool with them. Then you tranche that pool up and create a security (this chart calls it ABS or asset-backed security; it's the same thing as MBS or REMIC for present purposes). Then you take those low-rated subordinate tranches and put them into a pool with a bunch of other stuff (commercial security tranches, corporate debt, junk bonds, heaven knows what), and then you tranche that up into a new thing called a Collateralized Debt Obligation, the "beauty" of which is that it's an actively traded, not static pool, so that while you might know what's in it the day you bought part of it, you may never know what's in it after that. Then you take the lowest possible tranche of the CDO--the "equity" portion or the very first part to take any losses, which is so high-risk it is referred to as "toxic waste," the stuff that is unrated by the rating agencies because it has no "credit support" whatsoever--and you put it in a pension plan managed by some goofball who thinks that it must be a good deal because a party who owns some of the higher rated tranches--the ones you "support" with your equity piece--tells you that if the planets align and the Messiah returns and everybody rolls a lucky seven, you'll make 20%!

I'm still not sure everyone is getting the picture here, so let's try this: the subordinate tranche of a subprime ABS/MBS is a "pig." With or without lipstick. The equity tranche of a CDO made up of subordinate tranches of a subprime ABS/MBS, mixed up with some other junk you do not understand, is a pig of a pig, distilled essence of pig, ur-pig, Total Ultimate X-Treme Mega Pig. Buying a B tranche of a subprime ABS is playing with matches. Buying the equity tranche of a CDO is playing with a blowtorch in the parking lot of the Exxon station while wearing a St. Lucia wreath on your head.

There is, you know, a reason they call these "equity" tranches. "Equity" in this context means "skin in the game." In what we might laughingly refer to as a "normal market," the party who issues the security keeps the "equity" piece, giving it some "skin in the game" and thus some incentive to make sure that underlying pool isn't total stinking piles of sewage. In what we no-longer-laughingly call the market we're in, the investment banks are "selling" their "skin" to your pension fund. Unless that IB has zero interest whatsoever in the rest of the CDO, they just pulled one on you. And the only party who could tell you who owns what--and could "appraise" the thing for you--is the IB, who will make a fee from selling it to you regardless.

Have I mentioned that there is such a thing as a "CDO Squared"? I bet you can guess what that is. Do I know whether there are pension funds buying pieces of a CDO2? No. Do you?

Teachers, firefighters, and police officers: you are not just the sucker at the table here. You are the sucker at the table of the suckers in the big casino of suckers. Your "managers" of your pension money just took the "opportunity" to assume the risk that Wall Street does not want to keep because it doesn't think a "20% return" is worth it.

Go. Call. Your. Benefit. Manager. Now.

Friday, June 01, 2007

WSJ: CRE Lenders, Investors may be Turning Cautious

by Calculated Risk on 6/01/2007 09:56:00 PM

From the WSJ: Skyscraper Prices Might Start Returning to Earth

... lenders have become worried that prices have gotten so high that buyers wouldn't be able to raise rents high enough to pay off their loans. In response, the interest rates that buyers have to pay have risen, and banks have demanded that buyers put up bigger portions of the purchase price.The following sounds familiar ...

At the root of the buying frenzy was a change in the way investors viewed real estate. In the past, buying a building was like buying a bond -- you were purchasing a stream of income for years to come. ... More recently, investors started treating buildings like stocks, betting that they could sell them later at significantly higher prices. Loans were being underwritten based on predictions of future cash flow.

"It used to be people bought for the current rents, and the upside was a surprise," said Cedric Philipp Jr., managing director of Commercial Mortgage-Backed Securities Structured Finance Group for Moody's Investors Service. "Now, they are banking on the upside."

Whatever

by Anonymous on 6/01/2007 04:53:00 PM

Via Reuters:

NEW YORK, May 31 (Reuters) - JPMorgan Chase & Co. is downplaying its role in subprime lending even as spectacular flameouts in that sector have turned the Wall Street bank into one of the biggest originators of risky mortgages.The King Is Dead. Long Live the King!.

"We don't do much in the subprime business -- at all," JPMorgan Chief Executive Jamie Dimon told investors earlier this month at the company's annual meeting. "It will be a good business, by the way."

In other banking news, via the Boston Globe:

ASHLAND -- In a scene reminiscent of the Cartoon Network bomb scare that paralyzed the Boston area in January, police shut down a strip mall yesterday in this small western suburb after employees at a Bank of America branch mistook a botched fax for a bomb threat.

Frustrated shop owners said the branch overreacted to the strange fax, which turned out to be an in-house marketing document sent by the bank's corporate office.

Frankly, that's the first I've ever heard of anyone actually reading a fax from corporate marketing. Guess it wasn't such a hot idea.

And via the Associated Press:

ATLANTA - On an episode of A&E's popular reality series "Flip This House," Atlanta businessman Sam Leccima sits in front of a run-down house and calls buying and selling real estate his passion.

Now authorities and legal filings claim that Leccima's true passion was a series of scams that included faking the home renovations shown on the cable TV show and claiming to have sold houses he never owned.

You mean this whole flippin' thing was just some kind of made-up teevee ripoff? I wonder if the bondholders are going to sue A&E . . .

Happy Friday afternoon, all.

Many Builders Building Spec Homes to Liquidate Land

by Calculated Risk on 6/01/2007 02:42:00 PM

According to Hovanian (via Briefing.com hat tip Brian)

[Land sales have] "just really slowed to a complete trickle with very few buyers of any type out there"So homebuilders are building spec homes to liquidate land:

"that's part of the reason why you do see many home builders resorting to selling spec homes because there's really a way of liquidating the land portfolio."Can't sell it? Build on it. With too much inventory already on the market, I wonder how this will work out for the homebuilders ...

Wal-Mart Cuts Capital Spending

by Calculated Risk on 6/01/2007 11:27:00 AM

A press release from Wal-Mart states that Wal-Mart plans to build "190 and 200 new U.S. supercenters during this fiscal year". This is a significant reduction from the announced plans just six months ago:

In October 2006, the Company had announced that its fiscal year 2008 growth plans included between 265 and 270 supercenters in the United States.This will result in approximately a 10% reduction in capital spending for Wal-Mart:

[The] strategy is expected to reduce capital expenditures for fiscal year 2008 to approximately $15.5 billion, down from the previously projected $17 billion ...This reduction in spending by Wal-Mart is a sign that the commercial real estate boom might be ending. And, as I keep pointing out, continued strong non-residential investment is one of the keys for keeping the U.S. economy out of recession.

May Employment Report

by Calculated Risk on 6/01/2007 09:10:00 AM

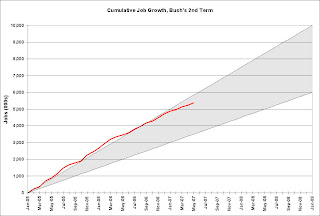

The BLS reports: U.S. nonfarm payrolls rose by 157,000 in May, after a downward revised 80,000 gain in April. The unemployment rate was steady at 4.5% in May.  Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

Here is the cumulative nonfarm job growth for Bush's 2nd term. The gray area represents the expected job growth (from 6 million to 10 million jobs over the four year term). Job growth has been solid for the last 2 1/4 years and is near the top of the expected range.

The following two graphs are the areas I've been watching closely: residential construction and retail employment.

Residential construction employment decreased by 1,300 jobs in May, and including downward revisions to previous months, is down 137.9 thousand, or about 4.0%, from the peak in March 2006. This is probably just the beginning of the loss of hundreds of thousands of residential construction jobs over the next year or so.

Note the scale doesn't start from zero: this is to better show the change in employment.

Retail employment lost 4,900 jobs in May. As the graph shows, retail employment has turned positive in recent months. YoY retail employment has also turned positive.

The expected reported job losses in residential construction employment still haven't happened, and any spillover to retail isn't apparent yet. With housing starts off over 30%, it's a puzzle why residential construction employment is only off about 4%. It is possible this puzzle has been solved (see: Residential Construction Employment Conundrum Solved?), but we will not know until the yearly revisions are announced.

Subprime Update: We Built This City on Rock and Roll

by Anonymous on 6/01/2007 09:05:00 AM

This is important data to contemplate, since credible claims have been made that a lot of new home purchase volume over the period in question was running on the fumes of the most marginal borrowers--stated income high-CLTV subprimes--and that any cutback in that kind of lending spells disaster for the home builders. And we have seen some "voluntary" tightening of this exact kind of subprime credit; we have also just heard the OCC hinting loudly at a regulatory "involuntary" tightening here.

So take some white-out to all the red and yellow parts of the bars on this chart, and then do the math. Ick.

Note: "Verbal verification" means "oral" (phone) verification of employment, but not of income. (You call up Calculated Risk and ask, "Does Tanta really work for you? OK, thanks.") It is, in other words, what you all think of as "stated income." The "none" category includes loans that do not even state income. They probably don't even "state" employment; if the borrower does fill out the box on the application for "employer," no one verifies that on the "none" loans. So on the "verbal" loans you know the borrower is employed but you don't know how much they actually make; on the "none" loans you don't know nuthin' 'bout nuthin'.