by Calculated Risk on 5/18/2007 06:08:00 PM

Friday, May 18, 2007

Subprime delinquencies higher than reported

Via Mathew Padilla at the O.C. Register: Subprime delinquencies higher than reported. Padilla writes:

Forget that 13% subprime delinquency number you heard about so much in the press ... I quizzed the MBA and got this in response from Jay Brinkmann, vice president of research and economics:... our latest subprime numbers are 14.4% delinquent by at least one payment, plus another 4.5% in foreclosure, for a total of 18.9% either delinquent or in foreclosure. For just subprime ARMs that number is 21.1%...

Wells Fargo: SoCal Homes Prices to Fall 6% Through '08

by Calculated Risk on 5/18/2007 12:30:00 PM

From Jon Lansner at the O.C. Register: Wells Fargo sees SoCal home prices down 6%-plus through '08

Scott Anderson, senior economist at Wells Fargo Bank, sees SoCal median home sales prices falling 2.3% this year and 4.1% in '08.And Anderson on the impact of the housing bust on the SoCal economy:

... it appears the “direct” impacts from the drop in housing demand has yet to be fully realized in the economic and payroll data, and we will still have to deal with the “indirect” impacts on household wealth and consumer spending. Credit quality has taken a major hit over the past year in Southern California. Expect a period of below average and perhaps disappointing economic performance as the residential housing adjustment continues.

Why Aren't Loans Designed For People Who Don't Need Them?

by Anonymous on 5/18/2007 12:17:00 PM

The following question was posed to Marketwatch's personal financial columnist yesterday. You can click here to see Lew Sichelman's answer. Or, being the Calculated Riskers that you are, you could offer alternative responses in the comments.

Note: "Statisticians should only talk to other statisticians" is not an acceptable answer, because we used that to great effect yesterday. ("We" in this case is Sippn.)

Question: For people who can't scrape together a 20% down payment, private mortgage insurance helps them get a home of their own. But what about the large segment of the population who can afford 20% down but don't want to pay it?

I'm in contract on a vacation home. Both I and my wife work white-collar managerial jobs in New York, so we have more than enough to buy the place outright. But we're lumped together with those that can't make 20% down and are forced to pay some 1%-2% more for PMI. That just doesn't make sense, not even for the lender, does it?

So rather than borrow 90% from a bank, I'll borrow only 80%. Then they make less money. Or maybe I'll borrow 90% but then pay some useless middleman his 1%-2% extra. Where's the market pressure to satisfy borrowers like me for whom mortgage insurance doesn't add any value?

While researching PMI, the key insight for me was reading the phrase "studies show that people who pay less than 20% are more likely to default." That exact phrase comes up all the time. In fact, I'd like to see those studies! When was the last one prepared, 1975? Isn't it odd that in our advanced world of actuarial analysis, no one breaks down those numbers to find that those low-down-payment defaulters also have lousy credit, don't have a job, are younger than 25 or whatever.

And isn't it odd that no bank seems to be interested in helping older, perfect-credit people with money get the property they desire without the wasted cost of PMI? Richard Campbell.

Residential Construction Employment Conundrum Solved?

by Calculated Risk on 5/18/2007 01:47:00 AM

The BLS released the Business Employment Dynamics statistics for Q3 2006 yesterday. This data is released with a substantial lag (Q3 2006 was just released), and it gives a fairly accurate estimate of the annual benchmarking for the payroll survey. In 2006, the benchmark revisions were substantial. On Feb 2, 2007, the BLS reported:

The total nonfarm employment level for March 2006 was revised upward by 752,000 (754,000 on a seasonally adjusted basis). The previously published level for December 2006 was revised upward by 981,000 (933,000 on a seasonally adjusted basis).This BED report suggests that the revisions will be down this year, especially for - you guessed it - construction employment! Based on the BED data, construction employment was overstated by 111K during Q3 2006. Since non-residential construction was still strong in '06, most of this downward revision will probably come from residential construction employment.

For those interested, the BED data is from the "Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW), or ES-202, program." The sources "include all establishments subject to State unemployment insurance (UI) laws and Federal agencies subject to the Unemployment Compensation for Federal Employees program."

Click on graph for larger image.

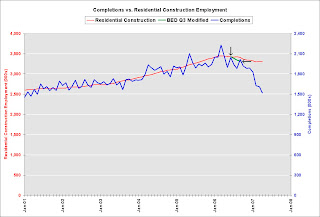

Click on graph for larger image.This graph shows housing completions vs. residential construction employment. The green line (Q3 only) with the arrows shows the impact of the BED revision on residential construction employment.

My guess is Q4 (and Q1 2007) will also show substantial downward revisions in residential construction employment. This probably means the expected job losses have been occurring, but simply haven't been picked up in the initial BLS reports.

Unfortunately, we will not know the size of the revisions until the advanced estimate is released in October.

Thursday, May 17, 2007

On Housing Permits and Starts

by Calculated Risk on 5/17/2007 01:10:00 PM

For those that enjoy statistics, Professor Menzie Chinn writes: Follow up on Housing Permits and Housing Starts: Do Permits "Predict"

In general I've ignored permits, and focused on starts and completions for housing. Professor Chinn argues there is some predictive value for permits:

Update: NOTE, the following graph is from Professor Chinn (see link). It is a log scale, and the gray area is future (not recession)."These results lead me to the conclusion that -- while permits might not be incredibly informative on their own for future housing starts -- they are useful when taken in conjunction with the gap between log levels of housing starts and permits, as well as lags of first differenced log housing starts and permits.

...

The model predicts continued decline in housing starts of 5.1% (in log terms), calculated as changes in predicted values (as opposed to using the actually observed value for 2007M04). Of course, with a standard error of regression (SER) of 0.055, a zero change lies within the 67% prediction interval."

Weekly Unemployment Claims

by Calculated Risk on 5/17/2007 12:35:00 PM

From the Department of Labor:

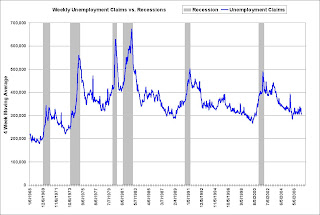

In the week ending May 12, the advance figure for seasonally adjusted initial claims was 293,000, a decrease of 5,000 from the previous week's revised figure of 298,000. The 4-week moving average was 305,500, a decrease of 12,000 from the previous week's revised average of 317,500.

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.This graph shows the four moving average weekly unemployment claims since 1968. The four week moving average has been trending sideways, and the level is low and not much of a concern.

A word of caution: weekly claims is a weak leading indicator.

Note that the Conference Board uses weekly claims as one of their ten leading indicators. From the AP: Economy may slow this summer

The Conference Board said its index of leading economic indicators dropped 0.5 percent, higher than the 0.1 decline analysts were expecting. The reading is designed to forecast economic activity over the next three to six months.Another word of caution: many economists, including former Fed Chairman Greenspan, have little confidence in the Conference Board leading indicators. In 2000, Greenspan commented that he thought the Conference Board leading indicators were useless in real time:

...

"The data may be pointing to slower economic conditions this summer. With the industrial core of the economy already slow, and housing mired in a continued slump, there are some signs that these weaknesses may be beginning to soften both consumer spending and hiring this summer," said Ken Goldstein, labor economist for the Conference Board.

"As an aside, the probability distribution based on the leading indicators looks remarkably good, but my recollection is that about every three years the Conference Board revises back a series that did not work during a particular time period, so the index is accurate only retrospectively. I’m curious to know whether these are the currently officially published data or the data that were available at the time. I know the answer to the question and it is not good!" [Laughter]Update: And Northern Trust's Paul Kasriel (hat tip ac) argues that the LEI has value: When The Facts Change, I Change My Model – What Do You Do?

Bernanke: The Subprime Mortgage Market

by Calculated Risk on 5/17/2007 10:50:00 AM

Remarks by Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke: The Subprime Mortgage Market

The recent sharp increases in subprime mortgage loan delinquencies and in the number of homes entering foreclosure raise important economic, social, and regulatory issues. Today I will address a series of questions related to these developments. Why have delinquencies and initiations of foreclosure proceedings risen so sharply? How have subprime mortgage markets adjusted? How have Federal Reserve and other policymakers responded, and what additional actions might be considered? How might the problems in the market for subprime mortgages affect housing markets and the economy more broadly?Short answer according to Bernanke: everything will be fine. See Bernanke's speech for his longer answers.

Tanta provides the translation (from the comments):

CR quoted the first paragraph. Here's how the rest of it goes:

2. Technology lets us find more subprime borrowers faster.

3. Securitization lets us find more bagholders faster.

4. We made a lot more loans this way.

5. Ownershipsocietyminoritypoorpeoplehelpedfeelgood.

6. Somehow, subprime borrowers still default more than prime borrowers do.

7. Number 6 is a recent problem.

8. ARMs have rates that go up, and home prices don't always rise. This is new, too.

9. Some of that loan underwriting was also kind of sucky.

10. It paid to make junk loans if you didn't have to own them.

11. Apparently some borrowers didn't get the memo.

12. Hedgies are bailing out the CDOs, so there's still some party left in the punchbowl. So far the banks can pass a breath test.

13. Even though this isn't a bank problem, the Fed is working with banks to help solve it.

14. We think someone should buy out those crappy securities and start modifyin', baby.

15. For some reason these borrowers think the lenders want to foreclose. Sure, it looked that way when the loan was made, but it's different now. Please call your lender, it's ready to make nice.

16. We're snorting a fine line here.

17-22. The best solution is to disclose to the borrower that these loans rarely make sense. It would be bad to ban them entirely, because they often do make sense.

23-24. We are also guiding the underwriting of the banks that aren't the ones making these loans.

25-26. None of this will affect the home market unduly, because jobs and wages will go up.

27-28. The market will correct any problem we can't mop up with disclosure requirements.

Why I Am Not An Analyst

by Anonymous on 5/17/2007 07:19:00 AM

On the way to my Yahoo! mailbox, I caught this headline, "Subprime Shakeout: Where Do We Go From Here?" That demanded to be read.

New Century had a 5-star Morningstar Rating for stocks during its collapse. Why? Good question. Admittedly, the company was risky, hence our above-average risk rating. Indeed, we even recognized that delinquencies would rise. In fact, we had assumptions of increasing charge-offs built into our New Century valuation model. But we underestimated two things.The implication that if New Century had been borrowing operating cash instead of lending capital, it wouldn't have gone bankrupt may not be the funniest thing you read today, but it has its charm. Yes, I'm aware that this is a reductio of the point really being made, which is that if New Century hadn't been using a warehouse line of credit to fund and carry its new held-for-sale loans (borrow short and lend long while you produce enough loans to securitize), and had instead used long-term investors' funds to sell those loans right out of the factory door (borrow long and lend long, really really fast), things would have been different. They surely would have.

First, we missed the risk that early payment defaults posed. As we stated, early payment defaults had never been an issue before, and we just did not see that risk on the horizon until it was too late. The risk we saw was loans defaulting as they reset from the "teaser" rate to a fully adjusted rate--the interest rate borrowers will ultimately have to pay after their low teaser rate expires--after two years.

Second, we didn't recognize how quickly the company's financing would disappear. New Century had been a darling of Wall Street, supplying banks with loans to package into new collateralized mortgage obligations. However, once the first problems arose, the very firms that had benefited from the flow of loans were the first to turn off New Century's financing spigot, demanding their money back and effectively killing New Century. The firm was out of cash, could not fund many loans already being processed, and was eventually forced to file for bankruptcy.

Arguably, if New Century had relied upon long-term debt instead of short-term financing, the company would probably still be alive today. No doubt, it would be struggling, as early payment defaults, high delinquency rates, and a reduced number of buyers of subprime mortgages would be taking its toll. But, we believe that with access to cash, New Century might have lived to see another day and maybe even stabilization in the market.

What does startle me is the failure to connect the two dots: the EPD problem and the financing problem. My contention is that we have seen unprecedented numbers of EPDs because we were not, actually, lending long, we were pretending to lend long. (This is my Bridge Loan theory about Alt-A and subprime: a loan structure that forces you to refinance in two years or face financial ruin is not a long-term loan, regardless of what the technical final maturity date is).

Traditionally, the "early" in "early payment default" is in reference to a pretty long loan life; the "traditional" average life of a 30-year mortgage just before the boom got underway after 2001 was about 7-10 years, so defaults in the first 90 days were weird and rare. There is, however, something odd about understanding a third-payment delinquency on a 2/28 "exploding ARM" made to a speculator as particularly "early." I mean, how many payments did we expect to take?

Something starts to suggest that we were just borrowing short and lending short, until of course those EPD rates hosed up the liquidity of the loans in the warehouse and we were suddenly borrowing long in real dollars and lending short in Monopoly money. You could see that as an issue of a lack of access to cash, even if like me you think the missing cash is repayments from borrowers rather than loans from investors. In any case I'm still struggling with the idea of how you live to fight another day by soldiering on with a neutral or negative carry. Presumably that would have been solved by the fall-off in loans originated: you can always make it up on lack of volume. So where do we go from here? Those of us who assumed the point was to make money making loans, rather than just make loans, can go back to bed. Everybody else should buy stock.

In other news, I received an email containing some color on current Alt-A and subprime trades, that contained this gem: "Sellers continue to look to product development to figure out ways to originate higher LTV product without subordinate financing."

What this means, for you civilians, is that since we replaced mortgage insurance with borrowed down payments until the down-payment lenders got burnt to a crisp right at the time the MIs decided they wouldn't play with us even if we tied a pork chop around our necks--those things are probably connected--we're back to "product development," which is going to be a bit tricky after that "nontraditional mortgage guidance" thingy told us to quit developing products that fake their way through a lack of borrower equity. But we're willing to try something tricky again, given that the alternative, limiting high LTV loans to people who can afford them, still sucks. What we need is a way for Joe Homebuyer to borrow long and lend short . . .

Wednesday, May 16, 2007

What Home Improvement Investment Slump?

by Calculated Risk on 5/16/2007 08:59:00 PM

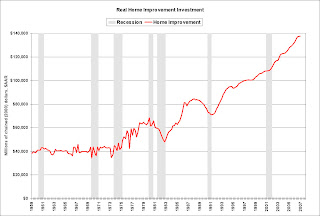

"We believe the home-improvement market will remain soft throughout 2007."Soft? Actually real spending on home improvement is holding up pretty well. If this housing bust is similar to the early '80s or '90s, real home improvement investment will slump 15% to 20%.

Frank Blake, Home Depot Chairman and CEO, May 15, 2007

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.This graph shows real home improvement investment (2000 dollars) since 1959. Recessions are in gray.

Although real spending was flat in Q1 2007, home improvement spending has held up pretty well compared to the other components of Residential Investment. With declining MEW, it is very possible that home improvement spending will slump like in the early '80s and '90s.

California Home Sales: Lowest Since '95

by Calculated Risk on 5/16/2007 08:05:00 PM

From DataQuick: California April 2007 Home Sales

A total of 34,949 new and resale houses and condos were sold statewide last month. That's down 12.2 percent from 39,811 for March, and down 28.5 percent from 48,894 for April 2006. Last month's sales made for the slowest April since 1995 when 27,625 homes were sold. April sales from 1988 to 2007 range from the 27,625 in 1995 to 66,938 in 2005. The average is 46,141. On a year-over-year basis, sales have declined the last 19 months.