by Calculated Risk on 8/02/2005 07:18:00 PM

Tuesday, August 02, 2005

Zero Savings and Housing

General Glut notes today that savers have reached the Rubicon of zero savings. But will they cross it? Dr. Hamilton had a recent discussion on savings and showed that the rate has been declining for 20+ years.

CNN has an article, The zero-savings problem, tying the recent lack of savings to the housing boom:

Even as a government report Tuesday showed the national savings rate at zero -- that's right nada -- the rise in the value of homes has given the average U.S. household a net worth of greater than $400,000, according to a separate report from the Federal Reserve.And that could mean problems ahead:

Household real estate assets have risen by just over two-thirds since 1999, and the run up has enabled consumers to spend more money than they are bringing home in their paychecks. They're viewing their homes almost like ATM machines, using home equity loans and refinancings to pull out cash and support a higher level of spending.

"[Rising home values] are making people feel they don't need to save," said Lakshman Achuthan, managing director of the Economic Cycle Research Institute.

That means they are spending more of their paychecks than they would otherwise. That's good news for the current economy but it could cause trouble longer term, according to some economists.

The low savings rate has kept consumers spending, which in turn has kept the economy growing.

"We've backed ourselves into a very dangerous situation," said Dean Baker, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research. "The economy is dependent on everyone consuming like crazy. If everyone heard my diatribe and said, 'Yeah, we better start saving,' the economy would go into a recession."

And while it's not going to be the warnings of economists that start people saving, the slowing of housing price growth or actual declines will put brakes on the spending as people will run out of equity they can tap.

The savings rate will also have more downward pressure as Baby Boomers start retiring and drawing down on retirement savings. While Social Security benefits count as income, withdrawals from 401(k) and other retirement accounts do not.

So if there is no change in the spending habits, the aging of the U.S. workforce could soon make zero or negative savings rates the norm.

"I find it just odd for all these economists and policy makers to be cheering for all this consumer spending when we're just digging ourselves into a hole," said Brusca. "With all the obligations we have ahead, to retirees and to ourselves, we have all the reasons in the world for people to be saving more and be controlling their spending."

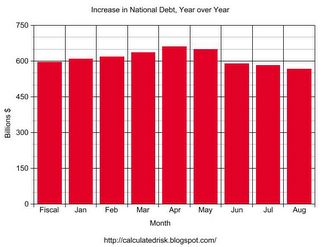

National Debt Increase: $566 Billion YoY

by Calculated Risk on 8/02/2005 05:53:00 PM

As of Aug 1, 2005 our National Debt is:

$7,869,521,621,947.05 (Over $7.8 Trillion)

As of Aug 1, 2004, our National Debt was:

$7,303,319,122,668.55

SOURCE: US Treasury.

Click on graph for larger image.

For comparison:

For Fiscal 2004 (End Sept 30, 2004): $596 Billion

For Jan 1, 2004 to Jan 1, 2005: $609.8 Billion

For Feb 1, 2004 to Feb 1, 2005: $618.6 Billion

For Mar 1, 2004 to Mar 1, 2005: $635.9 Billion

For Apr 1, 2004 to Apr 1, 2005: $660.9 Billion

For May 1, 2004 to May 1, 2005: $648.8 Billion

For Jun 1, 2004 to Jun 1, 2005: $588.0 Billion

For Jul 1, 2004 to Jul 1, 2005: $581.2 Billion

For Aug 1, 2004 to Aug 1, 2005: $566.2 Billion

It now appears that the debt increase for fiscal '05 will be slightly less than the record set in fiscal '04. The current record annual increase in the National Debt is $596 Billion for fiscal '04.

Housing: Mortgage Rates

by Calculated Risk on 8/02/2005 11:36:00 AM

UPDATE: See graph at bottom.

Mortgage rates bottomed in May 2003.

Click on graph for larger image.

Since May 2003 the 30 year fixed rate has been steady and the 1 Year ARM starter rate has risen almost 100 bps.

A couple of points: We haven't seen a substantial increase in rates yet.

Second, in the less than two years since rates bottomed, house prices have continued to rise.

Percent Increase since Q2 2003 (through Q1 2005 according to OFHEO):

California 37%

Florida 29%

Nationwide 18%

This raises some questions:

1) Why have house prices continued to rise?

2) Have homebuyers migrated from fixed instruments to ARMs to afford homes?

3) Did transaction volumes fall when the 30 year fixed moved above 6% in late summer '03 and mid-summer '04?

To try to address the third question, here is a graph of New Home Sales, Seasonally adjusted since Jan 2002. When the 30 year fixed rate was above 6% is shaded in gray.

During the last two years, it appears that when fixed rates rose above ~6%, New Home Sales faltered. Many buyers just switched to ARMs, but there are probably some buyers that insisted on the insurance of a fixed rate loan. This might be of interest since the 30 year rate is closing in on 6% again.

Monday, August 01, 2005

Housing, Layoffs, the UK and more

by Calculated Risk on 8/01/2005 02:12:00 AM

A potpourri of stories ...

My most recent post is up on Angry Bear: A Regulatory Substitute to Burst Housing Bubble? Fed Chairman Alan Greenspan, July 11, 2005:

"Bank Regulatory policies are neither designed nor used to influence asset prices in particular sectors of the economy. Rather, there purpose is to ensure adequate bank risk management ..."

Bloomberg: Greenspan Housing View Seen Hazardous by Wall Street Economists

Worry, say Wall Street economists including David Rosenberg of Merrill Lynch & Co. and Stephen Roach of Morgan Stanley.Danielle DiMartino: Job losses might herald bigger woes

The economists say the Fed must act, for a simple reason: The U.S. has become so dependent on real estate and construction to fuel growth and jobs that an eventual, wrenching correction has the potential to sink the entire economy.

"Act now and cut off the pinky, or wait till later and risk slicing off the entire hand," Rosenberg said in an interview last week. "Either way it hurts, but you can still type with nine fingers."

...

"The Fed is in some sense caught in a box," said Rosenberg, who estimates 60 percent of the U.S. is experiencing a housing-price bubble. "Housing has been this giant locomotive driving just about everything."

...

"There's enough of a risk that the Fed should be preemptive," Maury Harris, chief economist at UBS Securities LLC in Stamford, Connecticut, said in an interview. He recommends the Fed keep pushing up its short-term rate, now at 3.25 percent, until market forces raise mortgage rates as much as 0.75 percentage points. Mortgages are linked to long-term bond yields.

...

"The Fed behaved irresponsibly" by "over-stimulating housing," Edward Leamer, director of the Anderson Forecast Center at the University of California, Los Angeles, said in an interview.

...

"The Fed is probably going to raise interest rates somewhat faster because of the housing price bubble," said Gramley, who is now a senior economic adviser at Stanford Washington Research Group in Washington. "If they can engineer a monetary policy now that brings a nice smooth end to this run-up in home prices, they're less likely to have economic instability down the road,"

"Summer is typically a time when we see a dropoff in job cuts, but this year that slowdown has not materialized," said John Challenger, chief executive of outplacement firm Challenger, Gray & Christmas. "In fact, five out of the six largest job cuts announced so far this year have occurred since May."Stephen King: America and Britain: united by debt but divided by economic performance - so far

With that in mind, while most others waited out last week on tenterhooks until Friday's July labor report, my vigil will end Wednesday with the release of Challenger's July layoff report.

After all, the government's report looks to the past, while Challenger's looks to the future, as the announced job cuts turn into real job cuts.

Announced job cuts in May and June alone were nearly 200,000. This summer's cuts could easily surpass the total for the first four months of the year, when it is much more typical to see heavy downsizing.

The number of job cuts announced between May and August is typically 20 percent lower than in the first four months of the year, according to Challenger.

This break with the typical pattern has John Challenger, whose Chicago firm has been tracking layoff announcements since 1989, looking for a deeper meaning in the numbers.

"We haven't seen mega-layoffs like this in years," Challenger said. "If the summer surge proves to be the first sign of an eventual economic slowdown, this would be the weakest expansion in recent times."

... the biggest difference, at least from a cyclical point of view, probably lies with housing and the consumer. From the Bank of England's point of view, the UK economy has delivered three major surprises over the past 18 months. The first surprise has been the slowdown in housing activity given that short-term interest rates rose only to 4.75 per cent last year, hardly a threatening level by previous standards.Bloomberg: ECB Rate Cut May Hurt More Than Help, Economists Say

Surprise No 2 has been the consumer's response: house prices are now roughly flat year-on-year, yet consumers have retrenched more rapidly than the Bank had expected. And the third surprise has been that, on the back of all these housing and consumer shenanigans, interest rates are on the verge of falling once again, suggesting that the neutral, or structural, level of interest rates is a lot lower than the Bank of England ever seriously contemplated.

"If consumers are hiding in their bolt holes, it's because of the fear of higher unemployment and unsettling European policies," said David Brown, chief European economist at Bear Stearns in London. While the ECB may lower rates as a last resort, "a quarter-point rate cut is going to make very little difference to consumer or business confidence. It's a drop in the ocean."Sorry for all the Doom and Gloom to start the week.

Sunday, July 31, 2005

Sign of the Times: Bubble T-Shirt

by Calculated Risk on 7/31/2005 01:59:00 PM

Just for fun ...

Get yours here.

Friday, July 29, 2005

Bernanke: House Prices Unlikely to Decline

by Calculated Risk on 7/29/2005 08:07:00 PM

Bernanke was on CNBC today. From Reuters:

Top White House economic adviser Ben Bernanke said on Friday strong U.S. housing prices reflect a healthy economy and he doubts there will be a national decline in prices.Is it too early to start talking about the "Bernanke Put"?

"House prices have gone up a lot," Bernanke said in an interview on CNBC television. "It seems pretty clear, though, that there are a lot of strong fundamentals underlying that.

"The economy is strong. Jobs have been strong, incomes have been strong, mortgage rates have been very low," the chairman of the White House Council of Economic Advisers said.

The pace of housing prices may slow at some point, Bernanke said, but they are unlikely to drop on a national basis.

"We've never had a decline in housing prices on a nationwide basis," he said, "What I think is more likely is that house prices will slow, maybe stabilize ... I don't think it's going to drive the economy too far from its full-employment path, though."

Fed's Yellen: Fed Could Manage Housing Price Drop Impact

by Calculated Risk on 7/29/2005 04:15:00 PM

Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco President Janet Yellen spoke at a Community Leaders' Luncheon in Portland, Oregon. On housing, Dr. Yellen said:

"... if a sizable reversal in house prices were to occur, it probably would affect the economy mainly through the lagged effects of declines in wealth and increases in interest rates, rather than through widespread financial disruptions."Her speech was very upbeat, but she did ask:

You might well ask, “What about oil prices?” “What about the record trade deficit?” “What about the possibility of a housing bubble?” “What about the ‘conundrum’ of surprisingly low long-term interest rates?”Her answer on housing:

Whatever the source of the conundrum, clearly low long-term rates have contributed to the continuing boom in the housing market. The share of residential investment in GDP is now at its highest level in decades. The question on everyone’s mind, of course, is whether this source of strength in the economy could reverse course and become instead a source of weakness. Put more bluntly: Is there a housing “bubble” that might collapse, and if so, what would that mean for the economy? To begin to answer this question, we need to know what we mean by the term “bubble.” A bubble does not just mean that prices are rising rapidly—it’s more complicated than that. Instead, a bubble means that the price of an asset—in this case, housing—is significantly higher than its fundamental value.

One common way of thinking about housing’s fundamental value is to consider the ratio of housing prices to rents. The price-to-rent ratio is equivalent to the price-to-dividend ratio for stocks. In the case of housing, rents reflect the flow of benefits obtained from housing assets—either the monetary return from rental property, or the value of living in owner-occupied housing. Historically, the ratio for the nation as a whole has had many ups and downs, but over time it has tended to return to its long-run average. Thus, when the price-to-rent ratio is high, housing prices tend to grow more slowly or fall for a time, and when the ratio is low, prices tend to rise more rapidly. I want to emphasize, though, that this is a loose relationship that can be counted on only for rough guidance rather than a precise reading.

Currently, the ratio for the country is higher than at any time since data became available in 1970—about 25 percent above its long-run average. Of course, the results vary widely from place to place. For Los Angeles and San Francisco, the price-to-rent ratio is about 40 percent higher than the normal level, while for Cleveland the ratio is very near its historical average.

Closer to home, the figure for Seattle is just over 35. For Portland, it turns out that the price-to-rent ratio is a bit anomalous. Unlike the ratio for the nation and many of the cities I’ve mentioned, Portland’s ratio has been trending up, and this pattern has been going on since the late 1980s. This means that there’s not a stable long-run average ratio to use as a comparison for today’s ratio, so the analysis we did for the other cities wouldn’t be that meaningful for Portland. What we do know is that the pace of home price appreciation in Portland has been close to the national pace over the past few years, lagging behind somewhat in 2003 as the state struggled to recover from the 2001 recession, but mostly catching up in 2004 and early 2005 as economic growth picked up noticeably in the state. As of early this year, home prices in the Portland area were up 12 percent over a year earlier, only a bit below the national pace of 12½ percent. More recently, I’ve heard reports that upscale homes in the Portland area are increasingly being sold at above-asking price—a phenomenon we’re all too familiar with in the Bay Area! So it’s clear that Portland’s housing market has been hot, but I’m sure that’s no surprise to you.

In any event, as I said before, the fact that the ratios for the nation and many areas of the country are higher than normal doesn’t necessarily prove that there’s a bubble. House prices could be high for some good reasons that affect their fundamental value. The most obvious reason is the low level of mortgage rates. This stems both from very stimulative monetary policy and from the conundrum I discussed earlier. Conventional mortgage rates have dropped from around 6 percent in early 2004 to around 5 percent recently.

Other factors could also be raising housing’s fundamental value. For example, recent changes in tax laws may be having an effect. In 1998, tax rates on capital gains were lowered and the exemption from capital gains taxation for housing was raised to $500,000. Both of these changes would reduce the potential tax bite from selling one home and buying another. Another development, which may be making housing more like an investment vehicle, is that it’s now easier and cheaper to get at the equity—either through refinancing, which has become a less costly process, or through an equity line of credit. Both of these innovations in mortgage markets make the funds invested in houses more liquid.

So there are good reasons to think that fundamental factors have played a role in the unusually high price-to-rent ratio. But the bottom line here is fuzzy. It’s very hard to say how big a role these factors have played, so we don’t know how much remains unexplained. Frankly, even the best available estimates are imprecise, and they don’t definitively answer the question: Is there a bubble, and if there is, how large is it?

Given this uncertainty, my focus as a monetary policymaker is on trying to understand what kind of risks a drop in house prices would pose for the economy. One of the classic ways to do this is to ask “What if…?”—in other words, to pose a purely hypothetical question. In this case, the “what if” question might be, “What’s the likely effect if national house prices did fall by 25 percent, enough to bring the price-to-rent ratio back to its historical average?” Before going any further, I want to emphasize that I’m not making any predictions about house price movements, but instead, simply discussing how a prudent monetary policymaker could assess the risk.

First, there would be an effect on consumers’ wealth. With housing wealth nearing $18 trillion today, such a drop in house prices would extinguish about $4½ trillion of household wealth—equal to about 38 percent of GDP. Standard estimates suggest that for each dollar of wealth lost, households tend to cut back on spending by around 3½ cents. This amounts to a decrease in consumer spending of about 1¼ percent of GDP. To get some perspective on how big the effect would be, it’s worth comparing it with the stock market decline that began in early 2000. In that episode, the extinction of wealth was much greater—stock market wealth fell by $8½ trillion from March 2000 to the end of 2002. This suggests that if house prices were to drop by 25 percent, the impact on the economy might be about half what it was when the stock market turned down a few years ago.

Moreover, the spending pullback wouldn’t happen all of a sudden. Wealth effects—positive or negative—tend to affect spending with fairly long lags. So, a drop in house prices probably would lead to a gradual cutback in spending, giving the Fed time to respond by lowering short-term interest rates and keeping the economy steady.

Now let’s complicate things. Suppose house prices started falling because bond and mortgage interest rates started rising as the conundrum was resolved, say, because the risk premium in bonds rose due to concerns about federal budget deficits or other factors. Then we’d have the cutback in spending because of the wealth effect, plus there’d likely be further spending cutbacks, as borrowing costs for households rose. Furthermore, a rise in long-term rates would have effects beyond just households—it also would dampen business investment in capital goods through a higher cost of capital.

How manageable would this scenario be? Like the wealth effect, these added interest-rate effects operate with a lag, so, again, there probably would be time for monetary policy to respond by lowering short-term interest rates. This obviously would not be a “slam dunk,” but in many circumstances it would seem manageable.

A matter of more concern is whether this scenario would lead to financial disruptions that could cause spending to slow sharply and quickly. One issue that receives a lot of attention is the increasing use of potentially riskier types of loans, like variable rate and interest-only loans that may make borrowers and lenders vulnerable to a fall in house prices or increase in interest rates. I believe that the odds of widespread financial disruption on this count are fairly slim, although, clearly, some borrowers are vulnerable. First, the shift to these new instruments appears relatively modest overall. Second, the equity cushions available to both borrowers and lenders still seem, on average, to be pretty substantial. This is evident in looking at loan-to-value ratios, which have fallen, on average, as home valuations have risen faster than mortgage debt. In addition, most financial institutions enjoy comfortable capital positions, so they’re better able to weather any problems with their mortgage portfolios. Finally, some of the risk associated with mortgages has been transferred from banks to investors, as banks have sold off securitized bundles of mortgage debt. These investors may be in a better position to handle the associated risk. So, while there undoubtedly would be some fallout from a substantial drop in house prices, the financial system and consumers appear to be in reasonably good shape to handle the situation.

GDP: Three Takes

by Calculated Risk on 7/29/2005 03:11:00 PM

Dr. Duy considers how the FED will review the GDP data: Fed Watch: A Week of Data That Point to More Tightening ...

And Dr. Hamilton presents: New GDP data and recession probabilities

And pgl is reasonably positive on GDP: Strong Fixed Investment Demand Growth.

Three interesting views.

For those with positive views on the economy, there is nothing in this report that will change their opinion. For those that are negative on the economy (because of the housing bubble, current account and fiscal deficits, etc.), there is nothing in this report that will sway them either.

Dr. Aigner: Trouble in housing market no game

by Calculated Risk on 7/29/2005 11:06:00 AM

Economics Professor and former Dean of the UCI Graduate School of Management Dennis Aigner writes in the OC Register: Trouble in housing market no game, Region's house of cards ready to topple as prices reach unsustainable levels.

Are you familiar with the game Jenga, where players successively remove small wooden blocks from the bottom of a tower and place them on top, creating a progressively more unstable situation until one player causes the whole structure to tumble? (Our family record is 31 courses, by the way, if you want to compare notes.) The remaining players yell, Jenga!, we all clean up the mess, restack the blocks and begin again.See Dr. Aigner's commentary for some comparisons to foreign markets.

That's basically what's about to happen very soon in parts of California and several other "hot" housing markets around the country. Merrill Lynch recently issued a "bubble" warning for six California housing markets - San Diego, the Inland Empire, Los Angeles, San Francisco, San Jose and Sacramento, where "affordability" indexes are at historic lows. In other words, household incomes are way out-of-sync with home prices.

... it won't take a big uptick in mortgage interest rates to trigger a slow-down or retrenchment in prices, and the argument that such high prices are justified by insufficient supply coupled with strong demand just doesn't hold water now that we have gone beyond all rationality with respect to affordability across the board.

We're in the midst of a classic speculative bubble, and even the venerable Alan Greenspan referred to a bit of "froth" in certain housing markets in a recent speech. The UCLA Anderson Forecast, which has been warning of a break in the bubble for the past couple of years, echoed that warning again in its latest quarterly update and predicted a recession to follow even if it's a "soft landing."

A hard landing is more likely (where nominal prices actually fall) because houses are more overvalued than in past booms, inflation is lower and many people have been buying houses as investments.

But the most compelling evidence of a bursting bubble to come is the divergence of home prices and rents. In the United States over the past decade the ratio of home prices to rents has increased by almost 40 percent.

The increase is much higher in hot housing markets like Orange County (99 percent), where the ratio of median home price to average monthly rent now stands at 433:1.

To re-calibrate to more reasonable historical levels will require rents to rise sharply, which is constrained by household income growth, or home prices will have to fall, the only other possibility.

...

Over the past four years, 90 percent of the growth in U.S. GDP was accounted for by consumer spending and residential construction. Declines in the nation's biggest housing markets are likely to trigger a major economic slowdown.

It is not a question of whether this will happen but when, how dire will be the consequences on economic growth, and how long it will take to restack the blocks and begin again.

WSJ: What Housing Bubble?

by Calculated Risk on 7/29/2005 02:32:00 AM

Neil Barsky writes in the WSJ "What Housing Bubble?"

If you want to be scared out of your wits these days, you basically have two choices: go watch Steven Spielberg's latest, or listen to the hysterical warnings of economists and journalists about the imminent popping of our so-called housing bubble.I think I missed out on those "parental contributions"! Barsky lists 3 myths:

...

The reality is this: There is no housing bubble in this country. Our strong housing market is a function of myriad factors with real economic underpinnings: low interest rates, local job growth, the emotional attachment one has for one's home, one's view of one's future earning- power, and parental contributions, all have done their part to contribute to rising home prices.

• Myth #1. There is too much capacity: According to Census data, over the past 10 years, housing permits have averaged about 1.63 million units per year -- including multifamily units. Household formation has averaged 1.49 million families per year. So far, so good. But ... Roughly 6% of the new home sales were for second homes ... approximately 360,000 units every year were torn down either because they were nonfunctional, or because they were "tear-downs." When the latter two numbers are taken into account, the real number of new homes is closer to 1.2 million, or 19% fewer than the average number of new households formed each year.

• Myth #2. Risky mortgage products are fueling house appreciation: Sages from Warren Buffett to Alan Greenspan have warned of the increased risk from the use of new mortgage products, particularly adjustable-rate mortgages and interest-only mortgages. The theory here is that buyers are extending themselves to make payments, and when their mortgages reset they will be in trouble. ... As virtually every mortgagee in the country knows, most ARMs are fixed rate for the first two to seven years. Virtually all have 2% interest-rate caps. The average American owns his home for seven years. Why pay several hundred basis points to lock in rates he is highly unlikely to take advantage of?

• Myth #3. Speculators are Driving Home Prices: The media today is chock-full of stories of day-trading dot-com refugees who have found their calling buying homes and condos "on spec," with the hope of flipping the property for a higher price. Earlier this month, one Wall Street analyst published an article with the catchy headline: "Investors Gone Wild: An Analysis of Real Estate Speculation." Scary ... again, some common-sense thinking is in order. In Manhattan, where I live, friends buy apartments kicking and screaming, convinced they top-ticked the housing market. Is Manhattan special? Are speculators flipping Palm Beach mansions? I don't think so. Yet these markets are experiencing the same price appreciation as Las Vegas, Phoenix and Florida, where real estate investors are supposedly driving prices higher.