by Calculated Risk on 2/14/2009 08:01:00 PM

Saturday, February 14, 2009

Tanta Vive Gear: Happy Valentines Day!

To new readers, please see In Memoriam: Doris "Tanta" Dungey

From Tanta's sister Cathy on some new items:

They say “Tanta Vive” on the embroidery instead of the mortgage pig. Some of us who “sport the pig” already get looks from people and I’m sure this will just add to that but we encourage the questions. To find them in EBay you search on “ Tanta ” and you’ll see them all. I’m switching all future donations to the OCRF. [Ovarian Cancer Research Fund (www.ocrf.org)]Here is the link for Mortgage Pig Gear - the Tanta Vive items are the bottom.

These items are produced as they are ordered and we do apologize about the size and color confusion. The best method is to enter this information in the PayPal message box when completing the order.Note from CR: I have a few items - my favorite is the Hooded Sweatshirt! Thanks for everyone who bought gear - and helped with this great cause - and thanks to those who donated to the Doris "Tanta" Dungey Endowed Scholarship Fund too.

We will accept check orders outside of Ebay but that will slow things down. Please EMAIL: rwstick AT yahoo DOT com (Dick) with the item, size and color and we will return the cost with shipping. Once the check is received with shipping instructions we will process the order.

And now, from Tanta last year: Happy Valentines Day

From Mortgage Pig™. (click on Pig for larger image)

Saturday, December 06, 2008

Tanta's Mortgage Pig Wear for Charity

by Calculated Risk on 12/06/2008 11:48:00 AM

Update: Repeating this ... makes a great Holiday gift for the UberNerd in your family! And the proceeds go to fight cancer ...

From Cathy (Tanta' sister):

Back in October, after Tanta came home from the hospital and agreed to come to Ohio with me, we had an idea to create Mortgage Pig Wear and donate the proceeds from the sales to the UMMS Greenebaum Cancer Center.

We have friends in Springboro, OH who own a small, local embroidery company called Image Mark-it that is owned and staffed by the type of caring folks who would want to be involved in a project like this. Jumped at the chance, is more like it.

We enlisted her 16 year-old nephew (my son) to handle the shipping and for that he would receive $1.00 per item in his college fund. Tanta would provide the "quality control" or lovingly ride herd on him. She couldn't wait.

Over the past 4 weeks we have "digitized" the pig for the embroidery on sweatshirts and polos and created high quality photo transfers for T-shirts and sweatshirts. Tanta lived long enough to see the samples but not to see the items go into production and be offered for sale. I still can't believe it.

I worried about what to do with this on Saturday so I simply asked Tanta. She wanted us to proceed. My son and my husband both asked her as well - and both got the same answer "Please go ahead with The Mortgage Pig Wear".

In the last day or so as I read the various tributes to her, I saw references to cure vs care. So we've made a small change - we're offering the embroidered pig items with proceeds donated to the Ovarian Cancer Research Fund (www.ocrf.org) and the photo-transfer items split between UMMS Greenebaum and OSUMC James Cancer Centers.

I hope you enjoy wearing these as much as the folks at Image Mark-it and I have enjoyed creating them. We are planning to work very hard to keep up with demand - and for all of us it's a labor of love.

From CR: I believe these are the larger images:

| Holiday |

|

| Click on the Mortgage Pig™ for a larger image in new window. |

| Slap it |

|

| Convexity |

|

Thursday, November 27, 2008

Happy Thanksgiving!

by Calculated Risk on 11/27/2008 12:52:00 AM

Happy Thanksgiving to all! Note: Tanta is with her family celebrating Thanksgiving.

|

The Mortgage Pig™ is a Tanta creation. Here is her explanation of the origins of Excel Art and the Mortgage Pig™ (see here for Tanta's entire post including three Excel Art images):

|

| Click on the Mortgage Pig™ for a larger image in new window. |

I suppose this requires some explanation. Many years and versions of Excel ago, I was in some interminable conference call--I believe we were discussing general ledger interface mapping for HUD-1 line items regarding undisbursed escrow items on the FHA 203(k) in the servicing system upload, or perhaps we were watching paint dry--when I experienced one of those evolutionary breakthroughs for which the human race is justly famous. I stopped doodling on my legal pad and started defacing my spreadsheet. In a word, Excel Art was born.No wait! You can see for yourself ...

An entire running gag developed, centered on the character of Mortgage Pig and his Adventures. The Pig you see above is a newer version; the old Pig didn't wear lipstick (old pig was developed before we started selling loans to Wall Street). You can, of course, print these images, but outside of the context of viewing them in Excel, they simply become primitive, childlike doodles of no particular resonance. Viewing them as a spreadsheet, on the other hand, makes them profoundly amusing. Really. There's just nothing like sending someone a file named "GL Error Recon 071597" and having a pig pop up when the workbook is opened for a knee-slapping good time. If you're a hopeless Nerd with no particular aesthetic sensibilities.

Our own regular commenter bacon dreamz, who is also accomplished with Word Art, has (woe betide his employer) become adept at Excel Art as well, under my provocation, and has developed a way cool variation, Excel Movies. This involves creating a large number of worksheets with tediously copied and edited images that, when you ctrl-page down rapidly, create crude animation. It takes a very long series of conference calls to produce a really good Excel Movie, but it can be done. Unfortunately they're hard to display on a blog post. You'll have to take my word for it that they're hysterical.

Here is a Mortgage Pig™ exclusive: "Raindrops Keep Falling on My Pig" starring the Mortgage Pig™ by Tanta. This Excel Movie is from December 2007 - and remember to press ctrl-page down to animate the movie!

Raindrops Keep Falling on My Pig (Warning: this is a 2 MB Excel File).

And more Mortgage Pig™: Fed: Emergency Meeting Minutes, posted in Jan 2008:

|

For more Mortgage Pig Art see: Happy Valentine's Day and Mortgage Pig™ Fights Back

Happy Thanksgiving to all! CR

note: for those that don't know, my co-blogger Tanta is undergoing cancer treatment and has been unable to post.

Friday, September 12, 2008

Mortgage Pig™ Fights Back

by Anonymous on 9/12/2008 10:25:00 AM

I have been fighting the impulse to break my "no political posts" rule for days now, even though Mortgage Pig™ and I have been taking this all very personally. But Krugman finally pushed me over the edge.

Tuesday, March 25, 2008

Monday, March 10, 2008

Thursday, February 14, 2008

Tuesday, January 29, 2008

Options Theory and Mortgage Pricing

by Anonymous on 1/29/2008 11:02:00 AM

One of the hot topics of conversation lately is the idea of a mortgage “put option.” There seem to be more than a few people—including those who don’t exactly use the language of options contracts, like that weird couple featured recently on 60 Minutes—who are slightly confused about what the “optionality” of a mortgage contract is. There are also lots of folks who are wondering what will happen to mortgage pricing in general should a substantial number of folks decide to “exercise the put” on their mortgages. It seems wise to me to try to tease out what’s going on here.

First, mortgage contracts in the U.S. are not, actually, options contracts. You may peruse your note and mortgage at length now, if you didn’t do so when you signed them, and you will not find any “put” or “call” in there. Your note is a promise to pay money you have borrowed, and your mortgage or deed of trust is a pledge of real estate you own (or are buying with the borrowed money) as security for that note. That means, in short, that if you fail to keep your promise to pay the loan in cash, the lender can force you to sell your property at auction (to produce cash with which to pay the loan in full). Because the mortgage instrument gives your lender a “lien,” any sales proceeds are first applied to the mortgage debt before you get any of it.

People get very confused about this because it is often the lender who ends up buying the property at the forced auction. When that happens, it is basically because the lender simply wants to put a “floor” bid in the auction: the lender bids an amount based on what it is willing to lose (if any). Typically, the lender bids its “make whole amount” or the loan amount plus accrued interest and expenses. If someone else bids more than that, the lender is happy to let the property go to the higher bidder.

The lender might bid less than its make-whole amount; it might bid its “probable loss” amount. If the lender is owed $300,000 and doesn’t think it could ever end up recovering more than $200,000, it might bid $200,000 at the FC auction. The lender doesn’t actually want to win the auction; lenders are not really in the business of real estate investment or property management. However, the lender would rather buy the home at the auction and pay itself back eventually by re-selling the property later (as a listed property in a private sale instead of a courthouse auction) than let the property go for $50,000 (meaning the lender would recover only $50,000 on a $300,000 loan instead of $200,000). Nothing ever stops any third party from bidding $1 more than the lender’s bid and winning the auction (except, of course, any third party’s own inclinations).

We need to remember, then, right away, when anyone talks about “giving the house back to the bank” or “mailing in the keys,” we are already in the land of metaphorical language. The only situation in which “giving the house back to the bank” would literally be possible is if you bought the house from the bank (say, it was REO) and the contract explicitly gave you an option to sell it back to the bank, whenever you wanted to, at a price equal to your loan balance. Nobody writes REO sales contracts that way. In most cases, of course, you bought the house from someone other than a bank. You have no option to “put the house back” to the seller. You win only if it's "heads."

A “put option,” in the financial world, is a contract that gives the buyer of the put the right, but not the obligation, to sell something (a commodity, a stock, a bond, etc.) in the future at a predetermined price. On the other side of the deal, the “writer” of the put is obligated to buy the thing in question if the put buyer exercises the option. Some of you may already be a bit confused about “buyer” and “seller” here, but that’s an important point. You don’t get “free puts.” You buy puts. There is a fee or a “premium” that you pay for the option contract. If you do not exercise the option, the put-writer pockets that fee. If you do exercise your option, the put-writer pockets that fee (to offset his loss on the deal) and your gains on the ultimate sale of the thing are net of the option premium.

The point of a put is that you buy them when you want to be protected from falling prices: if you think there is a good chance that the value of something will fall in the future, buying a put that allows you the option of selling it next month at this month’s price might well be worth paying that option premium. But you do always pay an option premium and you do not get it back.

The opposite of the put option is the call option: it is the option to buy something in the future at a predetermined price. You buy calls when you think the value of the thing is likely to rise. You also always pay some premium or fee for a call.

Residential real estate sales and mortgage loans do not, actually, literally, have puts and calls in them. If you buy a home today, you assume the risk that its price may fall in the future. Your contract does not include an option for you to sell the house at the price you paid for it. Nor does the seller of the house have a “call”; the seller cannot force you to sell the house back to him at the original price if its value rises.

Your mortgage loan contract does not give you the right to simply substitute the current value of the house for the current balance of the loan: you do, in fact, risk being “upside down.” (The only time this isn’t true in the U.S. is with a reverse mortgage; those are written explicitly to have this kind of a feature, where the balance due on the loan can never exceed the current market value of the property. But of course reverse mortgages aren’t purchase-money loans.) Nor does the mortgage contract give your lender the right to buy your house from you for the “price” of the loan amount when that is less than its value. Mortgage lenders never do better than paid back. If the real estate securing your loan increases in value, that appreciation belongs to you (as long as you make your loan payments).

So why is it that people keep talking about “puts” and “calls” in terms of mortgage loans? That’s because mortgage contracts have features that can affect their value to the writer of the contract (the lender or investor) in a way that is analytically comparable, in some ways, to classic options. Options theory is applied to mortgages in order to price them as investments. (Strictly speaking, this is a matter of analyzing them so that a price can be determined.) The interest rate, then, that you get on a mortgage loan will depend, in part, on how the lender/investor “priced” the implied options in the contract.

The “implied put” in a mortgage contract is the borrower’s ability to default (walk away, send jingle mail, whatever you want to call it). We do not, generally, consider “distress” (that’s actually the formal term in the literature, for you Googlers) as an “implied put.” Some borrowers will fall on hard times and be unable to fulfill their mortgage contracts. This is a matter of “credit risk” and it is, analytically, a different matter of mortgage contract valuation. The “implied put” analysis is trying to capture the possible cost to the lender/investor of what we call the “ruthless” borrower. “Ruthless” isn’t really intended to be a casual insult; it is in fact the term we use to describe borrowers who can pay their debts but choose not to, because there is a greater financial return to that borrower in defaulting as opposed to not defaulting. It is “ruthless” precisely because there is not a contractual option to do this: the only way you can exercise the “implied put” is to default on your contract.

Many many people are very confused about this. When we talk about the “social acceptability” of jingle mail, what we are talking about is at some level the extent to which there is or ought to be some rhetorical or social “fig leaf” over ruthlessness. It seems to be true, after all, that most people are more likely to behave ruthlessly if they can call it something other than ruthlessness. (There are always people who have no trouble with ruthlessness; they often get the CEO job. Most of us have at least moderately strong inhibitions about ruthless behavior.) There is, therefore, a process in which the ruthless put is re-described in various alternative terms, or has alternative narrative contexts built up around it, such that it no longer “feels” ruthless. The borrower was victimized (by the lender, the original property seller, the media, the Man). The put premium was actually paid (“they charge me so much they can afford this”). The ruthless borrower is actually the distressed borrower (redefining what one can “afford” or what is necessary expense so that a payment you can make becomes a payment you “can’t” make).

Before anyone starts in on me, let me note that these fig leaf mechanisms are effective precisely because victimization, predatory interest rates, and truly distressed household budgets do really exist. They wouldn’t be very convincing otherwise. (Very few ruthless borrowers will claim it’s because of, say, alien abduction or something equally implausible.) I am not, therefore, asserting that all claims of predation or distress are “false.” I am simply pointing out that it is, after all, a hallmark of the not-usually-ruthless person who is nonetheless acting ruthlessly to rationalize his conduct.

I don’t offer that as some startling insight into human psychology. I offer it as an attempt to get some analytic clarity. When CR talks about lenders fearing that jingle mail will become socially acceptable, he’s not exactly saying that lenders fear that society will no longer stigmatize financial failure (“distress”). They are afraid that rationalization mechanisms will become so effective that true ruthlessness (which is historically pretty rare in home mortgage lending) will become a significant additional problem (in addition to true distress). And they fear this because, delusions to the contrary, those loans did not have enough of a “put premium” priced into them to cover widespread “ruthless default.”

In fact, the very language of options theory can function, for a certain class of ruthless borrowers, as the fig leaf. To say “Hey, I’m just exercising my put” is a retroactive reinterpretation of your mortgage contract to “formalize” the “implied put” so that you do not have to describe what you’re doing as “defaulting.” This strategy is apparently popular with folks who have some modest exposure to financial markets jargon and an unwillingness to lump themselves in with the “riffraff”—victims of predators and financially failing households and other “weaklings.” (Sadly, a lot of people who have a very high degree of exposure to financial markets jargon don’t need no steenkin’ rationalization. Like most sociopaths, they don’t understand why “ruthless” would be considered insulting or what this term “social acceptability” might mean. So if you’re hearing the “put” excuse, you are probably in the presence of a relative amateur.)

The other side of the problem in valuation of mortgage loans and mortgage securities is the “implied call.” The “call-like feature” in a mortgage contract is the right to prepay. In the U.S., all mortgage contracts have the right to prepay. (Some, but not all, have a “prepayment penalty” in the early years of the loan, but “penalty” here means a prepayment fee, not an actual legal prohibition on prepayment.) The reason the right to prepay functions like an implied call is that it gives the borrower the right to “buy” the loan from the lender at “par,” even if the value of the loan is much higher than “par.” If you refinance your mortgage, you are required only to pay the unpaid principal balance (plus accrued interest to the payoff date) to the old lender in order to get the old lien released. Unless the loan specifically has a prepayment penalty, you are not required to further compensate the old lender for the loss of a profitable loan. So a loan with a prepayment penalty has an implied call and a real call exercise price. A loan without a prepayment penalty, or past the term of its prepayment penalty, has a “free call.” (In the original lender’s point of view. There is always some price to be paid to get a new refinance loan; the borrower’s calculation of the value of refinancing always has to take that into account. Among other things, this fact results in mortgage “call exercise” being much less “efficient” than it is on actual call contracts, which makes the call much more difficult to value, analytically, for mortgages.)

While ruthless default might, historically, be rare, refinancing has been ubiquitous for decades now. It wasn’t always so easily available; your grandparents might never have refinanced a loan not because their existing interest rates were never above market, but just because there weren’t lenders around offering inexpensive refinances. In fact, refinances have been so ubiquitous for so long now that many people have come to think of the availability of refinancing money as somehow guaranteed. This isn’t just a naïveté about interest rate cycles, although it is that too. It is a belief that credit standards and operating costs of lenders never change, so that if someone thought you were “creditworthy” once, they’ll automatically think of you as creditworthy again, and that lenders can always afford to refinance you without charging you upfront fees.

People who price mortgage-backed securities have always known that the prepayment behavior of mortgage loans is impacted not just by prevailing interest rates, but also by the borrower’s creditworthiness, the lenders’ risk appetites, and the cost (time and money) of the refinance transaction. We were talking the other day about the prepayment characteristics of jumbo loans in comparison to conforming loans; the fact is that people who have the largest loans are the most likely to refinance at any given reduction in interest rate, since a reduction in interest rate produces more dollars-per-month in savings on a larger loan than it does on a smaller loan. Considering these types of things is very important to people who price MBS, because in fact prepayment behavior is both hard to “price” and absolutely critical to “pricing” mortgages as an investment.

MBS, unlike other kinds of bonds, are “negatively convex.” I have been threatening to talk about convexity for a while and I keep chickening out. It’s actually useful to understand it if you want to understand why mortgage rates (and the value of servicing portfolios) behave the way they do. The trouble is that convexity involves a whole bunch of seriously geeky math and computer models and normal people probably don’t want to go there. (I don’t even want to go there.) So as a compromise, this is a very quick and simple explanation of convexity.

The convexity of mortgages is a result of the “implied options” in them. Most people understand intuitively that the higher the interest rate on a loan, the more an investor would pay for that loan: if you had the choice today of buying a bond that paid you 6.00% and one that paid you 6.50%, you would probably not offer the same price for each of them. With a classic “vanilla” bond, the price you would offer would be a matter of looking at the term to maturity, the frequency of payments, the interest rate, and some appropriate discount rate.

The trouble with mortgages is that while they have a maximum legal term to maturity, they have an unpredictable actual loan life, because they have the prepayment “calls” implied in the contracts. The return on a mortgage is uncertain, because you might get repaid early, forcing you to reinvest your funds at a lower rate. On the other hand, the loans might just stay there until legal maturity, at an interest rate that is now below the market rate on a new investment. The problem, obviously, is that borrowers refinance most often when prevailing market rates have dropped (right when the investor might want the loans to be long-lived) and don’t refinance when prevailing rates have risen (right when the investor would like to see you go away). “Vanilla” bonds don’t behave this way. Vanilla bonds, like Treasury bonds and notes, are “positively convex.” Mortgages are “negatively convex.”

Here’s a comparative convexity graph prepared by Mark Adelman of Nomura (do pursue the link if you want more detailed information about MBS valuation). This graph plots three example instruments all with a face value of $1,000 and a price of par ($1,000) at 6.00%. The vertical axis reflects the change in price of the bond. The horizontal axis reflects the change in prevailing market yields. As you move to the left of 6.00%, you see that the price of the bond increases (it has an above-market yield); as you move to the right it decreases.

However, the three instruments do not increase or decrease in price in the same way. The 30-year bond has a steeper curve than the 10-year note, which is a function of the difference in maturities of the two instruments. The MBS isn’t just not as steep; it is a different shape. The 30-year bond and the 10-year note price functions create an upward-curving slope when you plot them against price/yield changes like this, and the MBS price functions create a downward-curving slope. The term “negative convexity” means, exactly, that downward curving slope.

What’s going on here is that when market yields fall (moving to the left in the graph), average loan life in an MBS pool will shorten markedly, as borrowers are “in the money” to refinance. At a relatively modest fall in market yields, the price of the MBS does increase (but the increase is much less than the increase in the other bonds). At a larger drop in market yields, the MBS price gets as high as it will ever get and then stops increasing at all. What happens here is that the underlying mortgage loans have become so “rate sensitive” that any additional decrease in market yield (increase in the spread between the bond’s coupon of 6.00% and current market coupons) is entirely offset by shortened loan life: loans will pay off so fast at this point that this “officially” 30-year bond really returns principal to the investor the way a 1-year or even 6-month Treasury bill would. No investor is going to pay more for the MBS at this point than it would for the very shortest-term alternative.

On the other side of the graph, you see that the MBS price declines more slowly than the vanilla bonds, although its curvature at this point is very like the 10-year. At this side of the chart, average loan life is increasing. (Mortgage bonds never go to zero prepayments or actual average loan life = 30 years.)

What all this implies is that, analytically, mortgages do have some sort of “option price” built in. (There is actually a name for this, the OAS or Option Adjusted Spread, a method of comparing cash flows of a mortgage bond across multiple interest rate and prepayment scenarios. It’s heavy math and modeling.) In the case of voluntary prepayment (refinancing or selling your home, basically), your “call” option has, in fact, been priced—it’s in the interest rate/fees you pay to get a refinanceable mortgage loan. Investors accept the uncertainty of mortgage duration by (attempting to) price it in.

All that, however, is about trying to price the full return of principal (which, in the case of a mortgage loan, is also the point at which interest payments cease). It isn’t trying to model the return of less than outstanding principal, which is what the “put” or ruthless default is. A refinancing borrower pays you back early at par. A defaulting borrower pays you back early at less than par. Standard MBS valuation models that were developed for GSE or Ginnie Mae securities (that are guaranteed against credit loss) do not “worry” about ruthless puts in terms of principal loss, since that loss is covered by the guarantor. What is causing some trouble these days with the “ruthless put” in the prepayment models is simply that this is an unexpected source of prepayment that isn’t correlating with “typical” interest rate scenarios. (We are seeing increased defaults in a very low-rate environment, because of the house price problem, which isn’t built into the prepayment models for guaranteed securities. Historically, prepayment models “expect” non-negligible numbers of ruthless puts only in higher-rate environments.)

It may help you to understand that we have been talking about how an investor might price an MBS coupon, which isn’t the same thing as the interest rate on a loan. In a Fannie Mae or Freddie Mac MBS, the “coupon” or interest rate paid to the investor might be, say, 6.00%. That means that the weighted average interest rate on the underlying loans in the pool is substantially more than 6.00%. There is the bit that has to go to the servicer, and there’s the bit that has to go to the GSE to offset the credit risk. The mortgages must pay a high enough rate of interest to provide 6.00% to the investor after the servicing and guarantee fees come off the top. In essence, then, MBS traders set the “current coupon” or the coupon that trades at par, the GSEs set the guarantee fee and/or loan-level settlement fees that cover the credit risk, the servicer sets the required servicing fee, and all that adds up to the “market rate” for conforming mortgage loans (plus mortgage insurance, if applicable, which is conceptually an offset to the guarantee fee).

One way of describing the situation we’re currently in is that borrowers are continuing the short loan life of the boom (which was made possible by easy refi money and hot RE markets) by substituting jingle mail for refinancing. That increases credit losses to whoever takes the credit loss (the GSEs and the mortgage insurers), decreases servicer cash flow (a refi substitutes a new fee-paying loan for the old loan; a default substitutes a no-fee-paying problem for the old loan), and makes everyone’s prepayment models go whacky-looking. This is one reason why it obviously wasn’t a good time for MBS traders to be told they’d be suddenly getting jumbos in their conforming pools; at some level the response to that could be summed up as “we don’t need one more thing that defies analysis.”

Ultimately, there is no way anyone can mobilize “social acceptability” as a defense against the ruthless put (even if you wanted to). The industry has, in fact, created the conditions in which it’s rational, and as long as it’s rational it will go on. Just as it was rational to buy at 100% LTV. The only possible way to get back to an environment in which ruthless default is rare is to abandon the “innovations” that give rise to them: no-down financing, wish-fulfillment appraisals, underpriced investment property loans, etc. The administration is currently pushing for increasing the FHA loan amounts and the FHA maximum LTV up to 100%. This is not likely to remove the incentive to take another reckless loan on a still-too-high-priced house. If we aren’t going to ration credit with tighter guidelines and loan limits, then it will have to be rationed with pricing: eventually the models will “solve” the problem by increasing the costs of mortgage credit. You cannot simply keep writing “free puts.”

Tuesday, January 22, 2008

Saturday, January 19, 2008

GuestNerds: The Pig and The Balance Sheet

by Anonymous on 1/19/2008 10:00:00 AM

We get a lot of questions about accounting issues these days. People are concerned about accrual accounting, particularly as it relates to Option ARMs or negative amortization and the income treatment of accrued but unpaid interest. This issue always butts up against the question of how mortgage holders reserve against losses on loans, or determine the extent to which capitalized interest is or is not ultimately collectable. We've also posted some news stories regarding the uproar over SFAS 114 treatment of modified mortgages, which really get down into the weeds in terms of mortgage accounting and which are, therefore, hard to follow without a basic understanding of general mortgage asset accounting. Finally, a number of people have been asking, as we keep seeing more and more reports of write-downs at banks and investment banks, how long this writing-down is going to go on, and how it is really calculated.

Some of you--bless your lovely hearts--may be entirely innocent of any background in accounting. You may be struggling to follow the conversation in part because you make the common civilian error of forgetting that bank accounting is "backwards." To you, a loan is a liability and a deposit account is an asset. To the bank, the loan is an asset and the deposit account is a liability. It does get more complicated than that, but it never makes any sense at all until you do get past that point.

Some of you, I know, come from the "real economy," or "widget-accounting," and you are stuggling with accounting concepts that make sense to you in terms of widget makers (or retailers), like inventory and receivables and warehouses, but become puzzling when they are applied to financial accounting. Some of you may be small business owners who work on a cash basis, not an accrual basis, so you may find financial accounting even more impenetrable.

I, who was never allowed into the accounting department unescorted am not an accountant, quite often struggle to make these things clear. Fortunately, our regular commenter Lama, who is a real accountant, has offered us a splendid GuestNerd post which walks us through the basics of accrual accounting, reserves, income, and asset valuation. I have added a few comments of my own, strictly from a banking perspective. Another of our regulars, the mighty bacon dreamz, has contributed illustrations to support Lama's text. I think you will find them enlightening.

Lama On Accrual Accounting and Reserves:

To understand how "other amortization" works, I guess you first need to know how accrual accounting works. Most individuals calculate their taxes based on cash basis accounting. You recognize income when you receive the cash (or check); you recognize expenses when you pay cash. Companies with simple cash transactions and not much equipment or inventory do not vary much if they use cash or accrual accounting (think newsstands, maybe a small consulting company).

Accrual accounting means you recognize revenue when earned, expenses when incurred. A gas station would not incur an expense when they purchase gas for resale. That station would incur the expense at the time the gas was sold. That’s because the gas’ cost was a cost to produce the sale. In the time between the purchase and subsequent sale, the company holds the gas as inventory as an asset on its balance sheet.

Another concept to keep in mind is that every asset on a balance sheet has a base and a reserve. The base asset value is the easy part. If someone borrows $100,000, you have a schedule with the $100,000 on it. The loan cost you $100,000 to make. If someone owes you the $100,000 and $5,000 accrued (unpaid) interest, now your schedule will have $105,000 as a current loan value.

Making a loan on the accrual basis means the lender is earning income based on what he is owed, not based on how much cash he receives, but how much the borrower owes. If there’s a $100,000 loan at 5%, the borrower owes $5,000 after one year. If the borrower pays $6,000, the loan balance is $99,000 with $5,000 paying interest and $1,000 paying principal. If the borrower pays $4,000, the loan balance is now $101,000, with $5,000 paying interest and $1,000 increasing the amount of the loan. That’s all there is to calculating the base asset. This is in keeping with every related principle of accrual accounting and has been done the same way since The Mortgage Pig wore short pants.

Now the reserve or fuzzy area. A reserve is the amount by which you will devalue the amount you record as the base asset. There are 3 basic ways to calculate a reserve. It’s possible to use any combination of 1, 2 or 3 within a portfolio. On debt instruments a company intends to hold (until maturity or involuntary termination), the reserve will be based on both Net Present Value of cash flows and collectability. The most accurate method is to specifically identify impaired assets. If you only think you’ll collect $90,000 NPV, the value is $90,000. Repeat the same for each loan. One might have a value of $0. [Tanta: this involves a credit analyst reviewing each loan at each reporting period, generally quarterly, to determine whether or to what extent it is impaired. You will find this method used on commercial portfolios, where there are fewer units of much larger loans which may not be homogenous or easily comparable to each other.]

The second method is a percent reduction of loan values based on historical experience. Say, if instruments of a certain type typically devalue by 5%, you’d apply that to the assets in the classification. Split the classified loans into as much detail as you think appropriate (there’s some detail in this area we don’t need today). [Tanta: this is the method typically used for loans classified as residential 1-4 family mortgages. In any but the tiniest portfolios, there are too many units to examine individually, and the guidelines and underlying collateral for residential 1-4 family are (supposed to be) homogenous enough that classification or grouping of loans for analytical purposes is considered sound practice as well as obviously efficient practice.]

The third type of reserve is called a general reserve. It is simply an educated guess applied to the entire portfolio. A manager might apply this on top of the other two types. This is also known as wetting your thumb and checking which way the wind is blowing. Years ago, the chairman of the SEC decried general reserves as “Cookie Jar” reserves and “Rainy Day Funds” and their use substantially diminished. Oh, in case you do some research on your own, Reserves = Allowances. [Tanta: in the context of banking, you will find loan reserves referred to as Allowances for Loan and Lease Losses or ALLL.]

The loan balance you see on the balance sheet or support schedule is the net of the base less reserves.

So, how does this affect Income? In accounting, everything is a transaction. Hence the Debits and Credits, which are just names. Your credit card company says “we’ll credit your account.” That means they are posting a credit to their Assets account “Loans." Assets are Debit accounts, so increases in Assets are Debits, decreases are Credits. Revenue is a Credit account, so increases in Revenue are Credits, decreases are Debits.

Reserves for Loans Losses is a Contra-Asset account. Contra-assets are credit accounts that piggyback off Asset accounts. That is to say, an increase to the Reserve is a decrease (credit) to the net Asset. The sister account to Loan Reserves on the Income Statement is the expense called "Provision for Credit/Loan Losses." To balance the journal entry, you post a debit to the expense, increasing it. So, in our example loan above, the base Asset is still $100,000 and the Contra-asset is $10,000, net $90,000. Expenses in the Income Statement will take the other side of the journal entry and increase (debit) for $10,000. In theory, there could be income from a reduction of the allowance account. I don’t see that happening these days. [Tanta: that would be the “cookie jar” problem: the temptation to over-reserve in very good times, which reduces current income to just “good,” in order to reduce those unnecessary reserves in future bad quarters, which would increase income in those quarters from bad to “good” (or just “acceptable,”) and therefore make the income over time appear more stable, which makes Wall Street analysts happy. It is not likely that anyone intentionally over-reserves in bad times, since it’s hard to withstand the effect that has on current income, whatever it might do for future quarters. I certainly do not believe that banks and thrifts were over-reserving during the boom, and as each quarter’s reports come out we see they are steadily increasing ALLL. This does not look like “smoothing” income to me.]

Something very likely to happen is that, in addition to principal, jingle mail senders will not be paying interest. If the bank can foresee a future default on our loan’s interest payments of $2,000, then they record a liability for $2,000 (not a reserve to an asset) and record a debit to Interest Income for $2,000 in the current year, reducing revenue.

Now, our total Net Income is reduced by $10,000 + $2,000, $12,000. Unless and until Cash is loaned or received, there is no effect on Cash.

It’s clear that there is some estimating and guessing done within the reserve calculations and bank managers are going to do all in their power to avoid restatements as none of them ever could have known (enter specific affecting crisis here). So if you want some moral outrage, don’t vent it on the accrual method, vent it against the reserves (more specifically, the people who estimate them). [Tanta: this is why I keep saying that the accounting treatment we are seeing for OAs is not "accounting games." The issue isn't the accounting rules for non-cash income; the issue is what assumptions went into estimating how much of that deferred interest is ultimately collectable.]

Lama On Asset Valuation:

First of all, most assets are required to be valued at the lower of cost or market (assuming a market exists). Usually, the more liquid an asset, the closer the market value will be to cost. Cash is the logical extreme as cost always equals market. Then you have Accounts Receivable which is usually proximate. Next, Inventory can closely trace the actual cost. That is, it should, but companies buy things they can’t sell, they redesign products they make, causing component inventory to be worth little to the company. Even items that have value to someone else might be valued at very little because there’s too much cost involved in finding a buyer and transportation. I once audited a company that had hundreds of thousands of titanium pipes valued at cost. Well, they had no use and no customer for them. The best offer they got was from the original vendor, 15% of cost. That was my number. So it goes onto Capital/Fixed Assets. Here, market value is usually not important. Heavy equipment that might make lots of money frequently has a low resale value and huge transportation costs if it was sold.

Our debt instruments are, by their nature, very liquid. If the holder is interested in selling, they should be valued at market. If you don’t like the current market price, then the instruments are not for sale . . . ok, you don’t mark them to market, you mark them to discounted cash flows. This is where the “mark to make believe” has been and is happening.

[Tanta: banks and thrifts in the mortgage business have two categories of mortgage assets: HFS (held for sale) and HTM (held to maturity). The former is “inventory” and the latter is “portfolio investment.” HFS is marked to market. As Lama says, if you aren’t marking to a market price, then apparently you aren’t really trying to sell anything here (home sellers, take notes on this part). Eventually, if you cannot (or will not) sell your HFS pipeline, you will need to transfer it to HTM (if you have the capital necessary to hold loans to maturity), and at that point you record the loan at the lower of cost or market. In this case there is an original “write-down” of the asset if current market value is less than cost. After that, further write-downs will be necessary at each reporting period, as Lama indicates above, if the assets become impaired (or more impaired than they were when you originally put them on the books). So what we are reading in the news about write-downs of mortgages and mortgage-related assets these days involve a combination of mark-to-market adjustments (for anything in “inventory” or being taken out of HFS to HTM) and impairments of assets that have deteriorated since the asset value was originally recorded. No one is allowed to take a “once and for all” write-down of a mortgage asset; ALLL is based on your best projections of realized losses in the next 12 months (adjusted each quarter). Theoretically, every loan you own is subject to further write-down each quarter if in fact your estimate of collectability continues to deteriorate.]

Saturday, December 29, 2007

On Option ARMs

by Anonymous on 12/29/2007 02:15:00 PM

This is a bonus post for those of you who use Excel (or some other software with which you can read and play with .xls files). I'm afraid that those of you who do not possess such software will have to use your imagination here. It's not especially practical to post images of big spreadsheets on the blog, so if you want to see the numbers, you'll need to download the spreadsheets.

These links will download the spreadsheets:

LIBOR-Indexed OA Projection

MTA-Indexed OA Projection

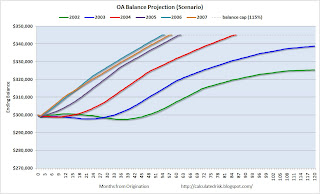

I made two of them for you to play with. Both show a to-date balance history, plus a future balance projection, for a hypothetical Option ARM with payments beginning in 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, or 2007. The loan terms are identical for each spreadsheet with the exception of the index chosen: one uses MTA, the other 1-Month LIBOR. The terms of these scenarios are in fact derived from real loan products out there, but of course there are other ways of structuring OAs. I am not making a claim about what product structure was most common (or most likely still to be on the books), as I don't have that kind of data.

What I had in mind for this exercise is to help people see, clearly, how these things work (some folks are still, Lord love you, a bit confused about OA mechanics. That undoubtedly includes some of you who have one. Remember that if you do, your loan might not work like this because the note you signed might have different terms regarding adjustment frequency, balance cap, margin, etc.) Besides that, I wanted to make a fairly simple point about the issue of resets, payment shock, and timing on these things.

That's why the spreadsheets show multiple vintages with identical loan terms: you can see that the actual speed of negative amortization and the forecast date of recast on these loans varies quite dramatically for the vintages, because of the huge impact of the very low 2002-2003 rate cycle. Each of these scenarios assumes that the borrower always makes the minimum payment from inception of the loan, and each assumes that future index values are identical to the most recent available index value (December 2007). Yet even in those circumstances, the earlier loans (2002 and 2003, especially) negatively amortize much more slowly than the later vintages.

My gifted co-blogger has actually created some lovely charts to help make that clear:  Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

If you've downloaded the spreadsheets, you can play around with them a little in terms of the future interest rates on these loans, and you can see how the recast date (the date the balance hits the balance cap and the loan payment must be recast to fully amortize over the remaining term) moves forward or back depending on what you do with the rates. This is one reason why modeling actual portfolios of OAs is such a challenge: you have to make assumptions about what will happen with the underlying index.

Of course, in actual portfolio modeling, you would also not assume that every borrower will always make the minimum payment. You would have to look at actual borrower performance to date, and calculate some "average" behavior or project each borrower's past behavior patterns into the future. I am not making the claim that all borrowers always make the minimum payment from inception; I'm trying to show what would happen, in some examples, if a borrower did that. I have heard estimates from different OA portfolios of anywhere from one-third to ninety percent of borrowers who have, historically, done that.

One other thing I wanted to make clear by providing these examples is the mechanics of payment increases for a very common OA type. The product shown in these spreadsheets allows for annual payment increases, but monthly rate increases. (That is how the potential for negative amortization gets created: the payment does not automatically adjust to match the new interest rate each month.) The eventual recast hits at the sooner of the loan reaching 115% of its original balance or 120 months. We know that a recast is nearly always a huge shock, given a low enough introductory rate. But this loan does involve payment increases of up to 7.5% each year (i.e., the next year's payment can be as much as 107.5% of the prior year's payment).

With the later vintage loans, especially, I for one have no confidence that the borrower was qualified at realistic enough original DTIs to withstand several years of payment increases, even before that nasty shock of the recast.

You may if you like change that introductory rate on these loans--I used 1.00%. You will see that increasing that introductory rate actually slows down the negative amortization in most scenarios. (That is because it creates a higher initial first year payment, which thus creates less of a shortfall between interest accrued and payment made.) I suspect that this fact about OA is surprising to some people, who think that folks who got a 1.00% "teaser" on these things got some real deal. In reality, a borrower who was given an introductory rate several points higher than that is probably doing much better, balance-wise.

My scenarios involve the assumption that the initial payment is fixed for only one year. There are OAs out there where the first payment change is two or even up to five years from the first payment date. (They will generally involve a higher introductory rate and margin.) You can change these spreadsheets to extend the original payment out for longer than a year, if you like, and you'll see just how much faster that balance cap hits when you extend the fixed payment period. Ouch.

Finally, while I chose the repayment periods I did quite arbitrarily, you will notice that for both the MTA and LIBOR scenarios, the most recent index value (December 2007) is substantially lower than it had been for quite some time. This means that my balance forecast here just happens to have picked up a relatively low last known index to project out into the future. Had we done this exercise several months ago, the projected future index value would have been higher, and hence the future negative amortization would have been faster. It's an issue to keep in mind as we look at portfolio and security projections regarding OA recasts; those will have to be updated from time to time as rate history unfolds.

And yes, there's a pig, if that makes you want to bother downloading the spreadsheets.