by Calculated Risk on 6/05/2008 12:00:00 AM

Thursday, June 05, 2008

Video of "Buy One, Get One Free" Real Estate Offer

Here is a video from TheStreet.com concerning that buy one house, get a second one free offer in Escondido, California. The video features Paul Kedrosky of Infectious Greed.

I've driven by the row homes, and they are on the corner of two busy streets - "Conveniently located on the corner of Midway Drive and Grand Avenue in Escondido" according to the builder - and not in the best neighborhood.

This is obviously just a gimmick to generate interest ... and it accomplished that goal.

Wednesday, June 04, 2008

The Residential Construction Employment Puzzle

by Calculated Risk on 6/04/2008 08:00:00 PM

An article in the WSJ today reminded me of the residential construction employment conundrum. From the WSJ: Housing Slump Hits Hispanic Workers, But Most Immigrants Remain in U.S.

The housing slump has disproportionately hurt Hispanic workers, provoking a jump in unemployment that has hit the immigrants among them the hardest, according to a new study.Here is the report: Latino Labor Report, 2008: Construction Reverses Job Growth for Latinos

...

Many undocumented workers don't appear on employment rosters because they work as independent contractors or are hired indirectly by big developers through subcontractors or labor brokers who don't officially hire every worker. "They were ghosts to begin with," says Rose Quint, an economist at the National Association of Homebuilders. Thus, she says, "the decline in employment is probably bigger than numbers are showing."

This graph shows the construction employment conundrum: why have starts and completions declined about 50% from the peak in 2006, and yet residential construction employment is off only 14%?

Click on graph for larger image in new window.

Click on graph for larger image in new window.Note that starts are shifted 6 months into the future since it takes a little over 6 months to complete a typical residential unit.

Last year Greg Ip at the WSJ reviewed an analysis from Deutsche Bank economists suggesting that the illegal immigrant explanation accounts for most of the missing job losses:

[E]conomists at Deutsche Bank estimate construction employment should have fallen about 900,000 since early 2006 when in fact it’s only down 150,000. They conclude 500,000 of the unexplained gap is attributable to layoffs of illegal Hispanic workers.To update the numbers, residential construction employment is off 477,000 from the peak, but there are still close to 1 million too many jobs based on starts and completions.

The uncounted illegal immigrant argument is important for the impact on the economy, but it doesn't seem to explain why the BLS employment numbers haven't fallen more. Although the BLS is missing the job losses for illegal workers on the way down, they also didn't count them on the way up either.

Although miscounted illegal workers probably explains some of the fewer than expected BLS reported job losses, there are two other explanations that make sense:

The answer is probably a combination of all of the above.

Merced Foreclosure Video

by Calculated Risk on 6/04/2008 06:43:00 PM

From the LA Times:

Merced provides a great contrast to Oceanside. Both areas have been inundated with foreclosures, and REOs are driving prices sharply lower.

In Oceanside (at least some areas), the prices have reached levels attractive to some investors. The rental market is tight in coastal north county San Diego, and these investors will provide somewhat of a floor on prices.

However in Merced, it appears there are simply more homes than households. This is farm land, and is definitely not a 2nd home location.

Accredited Home Lenders Closes Offices

by Calculated Risk on 6/04/2008 05:36:00 PM

Here is an email from Accredited:

| ||||||||||||||||||

Bernanke on Energy and Inflation: 1970s vs. Today

by Calculated Risk on 6/04/2008 03:50:00 PM

From Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke: Remarks on Class Day 2008

The oil price shock of the 1970s began in October 1973 when, in response to the Yom Kippur War, Arab oil producers imposed an embargo on exports. Before the embargo, in 1972, the price of imported oil was about $3.20 per barrel; by 1975, the average price was nearly $14 per barrel, more than four times greater. President Nixon had imposed economy-wide controls on wages and prices in 1971, including prices of petroleum products; in November 1973, in the wake of the embargo, the President placed additional controls on petroleum prices.It was a crazy time. I wasted both gas and time driving around looking for open gas stations, and then waiting in long lines.

As basic economics predicts, when a scarce resource cannot be allocated by market-determined prices, it will be allocated some other way--in this case, in what was to become an iconic symbol of the times, by long lines at gasoline stations. In 1974, in an attempt to overcome the unintended consequences of price controls, drivers in many places were permitted to buy gasoline only on odd or even days of the month, depending on the last digit of their license plate number. Moreover, with the controlled price of U.S. crude oil well below world prices, growth in domestic exploration slowed and production was curtailed--which, of course, only made things worse.

In addition to creating long lines at gasoline stations, the oil price shock exacerbated what was already an intensifying buildup of inflation and inflation expectations. In another echo of today, the inflationary situation was further worsened by rapidly rising prices of agricultural products and other commodities.It is worth reading Bernanke's views because that is the general consensus of the Fed. His comments on the Fed fighting inflation in the "medium term" further suggests the rate cuts are over for now - even if the economy weakens further. Inflation, and inflation expectations are just too high.

Economists generally agree that monetary policy performed poorly during this period. In part, this was because policymakers, in choosing what they believed to be the appropriate setting for monetary policy, overestimated the productive capacity of the economy. I'll have more to say about this shortly. Federal Reserve policymakers also underestimated both their own contributions to the inflationary problems of the time and their ability to curb that inflation. For example, on occasion they blamed inflation on so-called cost-push factors such as union wage pressures and price increases by large, market-dominating firms; however, the abilities of unions and firms to push through inflationary wage and price increases were symptoms of the problem, not the underlying cause. Several years passed before the Federal Reserve gained a new leadership that better understood the central bank's role in the inflation process and that sustained anti-inflationary monetary policies would actually work. Beginning in 1979, such policies were implemented successfully--although not without significant cost in terms of lost output and employment--under Fed Chairman Paul Volcker. For the Federal Reserve, two crucial lessons from this experience were, first, that high inflation can seriously destabilize the economy and, second, that the central bank must take responsibility for achieving price stability over the medium term.

emphasis added

Fast-forward now to 2003. In that year, crude oil cost a little more than $30 per barrel. Since then, crude oil prices have increased more than fourfold, proportionally about as much as in the 1970s. Now, as in 1975, adjusting to such high prices for crude oil has been painful. Gas prices around $4 a gallon are a huge burden for many households, as well as for truckers, manufacturers, farmers, and others. But, in many other ways, the economic consequences have been quite different from those of the 1970s. One obvious difference is what you don't see: drivers lining up on odd or even days to buy gasoline because of price controls or signs at gas stations that say "No gas." And until the recent slowdown--which is more the result of conditions in the residential housing market and in financial markets than of higher oil prices--economic growth was solid and unemployment remained low, unlike what we saw following oil price increases in the '70s.

For a central banker, a particularly critical difference between then and now is what has happened to inflation and inflation expectations. The overall inflation rate has averaged about 3-1/2 percent over the past four quarters, significantly higher than we would like but much less than the double-digit rates that inflation reached in the mid-1970s and then again in 1980. Moreover, the increase in inflation has been milder this time--on the order of 1 percentage point over the past year as compared with the 6 percentage point jump that followed the 1973 oil price shock. From the perspective of monetary policy, just as important as the behavior of actual inflation is what households and businesses expect to happen to inflation in the future, particularly over the longer term. If people expect an increase in inflation to be temporary and do not build it into their longer-term plans for setting wages and prices, then the inflation created by a shock to oil prices will tend to fade relatively quickly. Some indicators of longer-term inflation expectations have risen in recent months, which is a significant concern for the Federal Reserve. We will need to monitor that situation closely. However, changes in long-term inflation expectations have been measured in tenths of a percentage point this time around rather than in whole percentage points, as appeared to be the case in the mid-1970s. Importantly, we see little indication today of the beginnings of a 1970s-style wage-price spiral, in which wages and prices chased each other ever upward.

A good deal of economic research has looked at the question of why the inflation response to the oil shock has been relatively muted in the current instance. One factor, which illustrates my point about the adaptability and flexibility of the U.S. economy, is the pronounced decline in the energy intensity of the economy since the 1970s. Since 1975, the energy required to produce a given amount of output in the United States has fallen by about half. This great improvement in energy efficiency was less the result of government programs than of steps taken by households and businesses in response to higher energy prices, including substantial investments in more energy-efficient equipment and means of transportation. This improvement in energy efficiency is one of the reasons why a given increase in crude oil prices does less damage to the U.S. economy today than it did in the 1970s.

Another reason is the performance of monetary policy. The Federal Reserve and other central banks have learned the lessons of the 1970s. Because monetary policy works with a lag, the short-term inflationary effects of a sharp increase in oil prices can generally not be fully offset. However, since Paul Volcker's time, the Federal Reserve has been firmly committed to maintaining a low and stable rate of inflation over the longer term. And we recognize that keeping longer-term inflation expectations well anchored is essential to achieving the goal of low and stable inflation. Maintaining confidence in the Fed's commitment to price stability remains a top priority as the central bank navigates the current complex situation.

Although our economy has thus far dealt with the current oil price shock comparatively well, the United States and the rest of the world still face significant challenges in dealing with the rising global demand for energy, especially if continued demand growth and constrained supplies maintain intense pressure on prices. The silver lining of high energy prices is that they provide a powerful incentive for action--for conservation, including investment in energy-saving technologies; for the investment needed to bring new oil supplies to market; and for the development of alternative conventional and nonconventional energy sources. The government, in addition to the market, can usefully address energy concerns, for example, by supporting basic research and adopting well-designed regulatory policies to promote important social objectives such as protecting the environment. As we saw after the oil price shock of the 1970s, given some time, the economy can become much more energy-efficient even as it continues to grow and living standards improve.

Bernanke also spoke about productivity.

Moody's may Downgrade Ambac, MBIA

by Calculated Risk on 6/04/2008 12:57:00 PM

From AP: Moody's may downgrade Ambac, MBIA ratings (hat tip Nemo, Juan)

Haven't we been here before?

Cancellations, Yet Again

by Calculated Risk on 6/04/2008 12:04:00 PM

First, the outlook for housing is negative. Just because I mention a few minor shreds of good news for housing, doesn't mean my view has changed. It hasn't, especially for existing home sales and prices.

OK, for those hoping to buy at lower prices, the outlook is rosy. Now that we’ve gotten the semantics out of the way, the overall outlook remains negative for house sales and prices. With tighter lending standards, demand will remain weak, and supply is already at record levels and still rising - especially the supply of distressed homes. This record supply, combined with continuing weak demand, will put pressure on house prices, probably for several years, in real terms, in many areas.

Now let’s return to cancellations. The cancellation issue can be confusing.

When looking at new home sales, we are interested in net sales, but the Census Bureau reports gross new sales. A simple equation would be:

Sales (net) = Sales (gross) – Cancellations + Sales of earlier cancellations.In the long run, the cancellation terms balance out, and the Census Bureau numbers are what we want. In other words, Sales(net) = sales(gross). But in the short run, with cancellations increasing, the Census Bureau probably overestimates sales; and with cancellations decreasing, the Census Bureau underestimates sales.

We don’t have the raw data for cancellations and sales of earlier cancellations. However the public builders typically report net sales and cancellation rates. Using the public data, we can estimate net vs. gross sales for the industry, and adjust the Census Bureau estimates accordingly. Luckily the analysis isn’t too difficult: when cancellations rates are rising, net sales are typically below gross sales, and when the cancellation rates are falling, net sales are usually above gross sales. Right now cancellation rates are falling and the builders are reporting they are reducing their inventory of “unintended spec homes”, and net sales are above gross sales.

Currently cancellation rates are still significantly above normal for the home builders. As an example, Toll Brothers just announced a cancellation rate of 24.9%, far above their historical rate of 7%. But the key for adjusting the Census Bureau numbers is that the cancellation rate has declined from 38.9% two quarters ago. What matters for this calculation is the change in cancellation rate over the previous six months since that is the time it typically takes to build a home.

The same is true for other builders. Another example is Hovnanian: they reported a cancellation rate of 29%, down from 40% two quarters ago. Hovanian averaged 23% cancellation rate in 2004 and 2005 (cancellation rates are builder specific because of their downpayment and pre-qualification requirements).

Since cancellations rates are now falling, this suggests that the Census Bureau is currently underestimating sales for new homes. This is not a positive comment about these individual builders, but this helps analyze the entire market.

Possible Casual Dining Bankruptcy

by Calculated Risk on 6/04/2008 09:25:00 AM

From the WSJ: Bennigan's Owner In Crucial Credit Talks (hat tip Geoffrey)

The owner of national casual-dining chains Bennigan's, Ponderosa and Steak and Ale is in talks with its major lender GE Capital Solutions in an effort to stave off a possible bankruptcy filing ...Casual dining is a discretionary expense and is frequently one of the first expenses that consumers reduce during hard times.

The problems at Metromedia show just how difficult life has become for casual-dining chains. Consumers are cutting back on discretionary spending. That comes as food prices for everything from corn to steak are on the rise. Many of the companies are also highly leveraged, which is pushing them to seek protection from creditors.

Earlier this year, the parent companies of the Bakers Square, Village Inn and Old Country Buffet filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, citing fall sales and rising food costs. A host of other chains -- from Outback Steakhouse to Ruby Tuesday's -- are also struggling.

MBA: Purchase Applications Decline

by Calculated Risk on 6/04/2008 09:05:00 AM

It appears the MBA Purchase Index might be useful again. Note: the index wasn't useful when lenders were going out of business because of the method used to calculated the index.

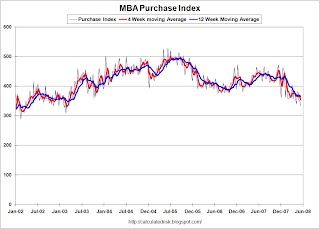

The MBA reports that the Purchase Index fell to 333.6, the lowest level since early 2003. Because of the changes to the index, we can't compare directly to 2003. Click on graph for larger image in new window.

Click on graph for larger image in new window.

This graph shows the MBA Purchase Index, and four week and twelve week moving averages.

Although we can't compare directly to earlier periods because of the changes in the index, this does suggest that sales of homes are continuing to decline.

Ed McMahon Receives Notice of Default

by Calculated Risk on 6/04/2008 12:15:00 AM

From the WSJ: Ed McMahon May Lose Beverly Hills Home

ReconTrust, a unit of mortgage lender Countrywide Financial, on Feb. 28 filed a notice of default on a $4.8 million Countrywide loan backed by Mr. McMahon's home. ... According to the filing, Mr. McMahon was then about $644,000 in arrears on the loan. It isn't clear whether Countrywide still owns the loan or is acting on behalf of investors who acquired it.We are all subprime now.

Mr. McMahon broke his neck in a fall about 18 months ago and hasn't been able to work, [Howard Bragman, a spokesman for Mr. McMahon] said. That health problem, along with the weak housing market and economy, has forced Mr. McMahon into foreclosure proceedings ...