by Anonymous on 8/20/2007 08:54:00 AM

Monday, August 20, 2007

MMI: We Have Met the Waldo and It Is Subprime

Happy Monday, everyone. Gather 'round while Uncle Bill Gross uses a metaphor from a children's book to explain to the unhip old farts what the young wizards have been up to.

Goodness knows, it's not a piece of cake for anyone over 40 these days to understand the maze of financial structures that now appears to be unwinding. They were created by youthful financial engineers trained to exploit cheap money and leverage, who showed no fear and who have, until the past few weeks, never known the sting of the market's lash.Don't be fooled by the piece of cake: it really involves fungus (after the Waldo part), so sorry about your breakfast.

REO Auction Shows Steep Price Decline In San Diego

by Calculated Risk on 8/20/2007 01:29:00 AM

From the WSJ: Countrywide Begins Staff Layoffs

An auction of about 135 foreclosed homes in San Diego Saturday provided more sobering news for mortgage lenders. Ramsey Su, an investor and former real-estate broker who attended, calculated that the high bids for the homes averaged 67% of the prices they fetched when they were last sold, mostly in 2004 or 2005. At a similar auction in San Diego in May, the average was 73%.Here is some more info directly from Ramsey:

Twenty nine properties that were in the May auction did not close escrow and were included in the August auction. These same properties sold for 87% of the May auction prices. The lenders took an extra 13% loss in just 3 months plus holding cost, that is assuming they will close this time.Ramsey also added that the "average price of the auction list, at the last sale, was only $413,000". So the auctions are "not signaling any problem at the higher end of the market". At least not yet.

Sunday, August 19, 2007

Fed: Spending May Slow as Housing Falters

by Calculated Risk on 8/19/2007 11:21:00 PM

From the NYTimes: Debt and Spending May Slow as Housing Falters, Fed Suggests

A new research paper co-written by the vice chairman of the Federal Reserve says that ... consumer spending may slow down over the next few years.Update: Some excerpts:

The paper will be presented this morning by [Fed Vice Chairman] Donald L. Kohn ...

[Fed economist] Ms. Dynan and Mr. Kohn say that higher housing prices made many homeowners feel wealthier and more willing to take on debt, which they then used to finance more spending. This spending helped to keep the economy growing at a healthy pace since the last recession ended in 2001.

But the increase in debt “is not likely to be repeated,” ...

The Fed’s study, which has been in the works for months, helps highlight some of the difficulties that policy makers are facing.

...

In some cases, the authors said, homeowner families might have taken on more debt than was wise, out of a misplaced belief that the rise in prices would continue for years.

The Fed’s analysis is noteworthy because consumer spending has been arguably the economy’s biggest strength since 2000.

"... substantial evidence suggests that households are not always fully rational when making financial decisions (Campbell, 2006). One can imagine a variety of reasons why households might take on more debt than is rationally appropriate. For example, a rise in house prices might make households feel wealthier than they are, perhaps because they do not recognize the increase in the cost of housing services; as a result, they might borrow too much and be left underprepared for retirement. Alternatively, households may suffer self-control problems so that a relaxation of borrowing constraints spurs borrowing that, in the long run, lowers rather than raises utility. Or households might mistakenly extrapolate recent run-ups in house or equity prices and take on too much debt to finance investment in these assets." emphasis addedOn the danger of so much debt:

"... household spending is probably more sensitive to unexpected asset-price movements than previously. A higher wealthto-income ratio naturally amplifies the effects of a given percentage change in asset prices on spending. Further, financial innovation has facilitated households’ ability to allow current consumption to be influenced by expected future asset values. When those expectations are revised, easier access to credit could well induce consumption to react more quickly and strongly than previously. In addition, to the extent that households were counting on borrowing against a rising collateral value to allow them to smooth future spending, an unexpected leveling out or decline in that value could have a more marked effect on consumption by, in effect, raising the cost or reducing the availability of credit."

Housing: Looking Ahead

by Calculated Risk on 8/19/2007 03:40:00 PM

Right now it appears housing is about to take another significant downturn.

But someday housing will bottom.

And I'm starting to see the first signs - not of a bottom - but that it might be worth looking ahead to the bottom. Blasphemy to some, I'm sure.

Defining a Bottom

The first step in predicting a bottom is to define what we mean. I think a bottom for new construction is very different than a bottom for existing homes. For existing homes, the most important number is price. So the bottom for a particular location would be defined as when housing prices bottomed in that area. Historically, during housing busts, existing home prices fall slowly for 5 to 7 years - so I'd expect to start looking for the bottom in the bubble areas in the 2010 to 2012 time frame.

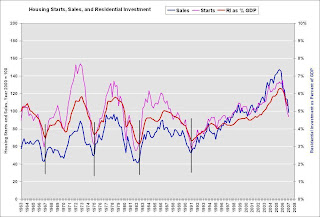

For new construction, we have several possible measures of a bottom. The following graph shows three of the most commonly used: Starts, New Home Sales, and Residential Investment (RI) as a percent of GDP.

NOTE: Sales and starts are normalized to 100 for year 2000. The purpose of this graph is to show the peaks and valleys of starts, sales, and RI. DO NOT use to compare sales to starts! Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

The four previous bottoms, as defined by Residential Investment, are marked with a vertical line. In general the three indicators bottom together, although starts bottomed before investment in 1982.

Overall I think we can use Residential Investment (or RI as a percent of GDP) to define a bottom for housing investment (but not prices).

The very tentative positive signs. The first possible piece of good news is that the NAR reported inventory declined from the record in May to a 4.196 million units in June.

The first possible piece of good news is that the NAR reported inventory declined from the record in May to a 4.196 million units in June.

Total housing inventory fell 4.2 percent at the end of June to 4.20 million existing homes available for sale, which represents an 8.8-month supply at the current sales pace, the same as a downwardly revised 8.8-month supply in MayOther sources have reported that inventory levels have increased, and I do expect inventories to continue to rise somewhat through the summer. I also expect the months of supply (inventory / sales) to continue to rise as sales decline. And more bad news: the number of REOs (bank Real Estate Owned) will certainly increase dramatically in the coming year. That sounds grim, but the good news is we might be nearing the peak of existing home inventory in raw numbers - and that could be the first baby step towards a bottom.

Another piece of potential good news is that it appears the homeowner vacancy rate (from the Census Bureau) might have peaked.

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.This graph shows the homeowner vacancy rate since 1956. A normal rate for recent years appears to be about 1.7%. There is some noise in the series, quarter to quarter, but it does appear the decline in Q2 was statistically significant.

The rental vacancy rate has been trending down for almost 3 years (with some noise). This was due to a decline in the total number of rental units in 2004, and more recently due to more households choosing renting over owning.

These vacancy rates are very high, but it does appear the rates have stopped climbing and - at least for rental vacancies - has started to decline. As starts decline (see Forecast: Housing Starts), inventory should stabilize and then decline, and the vacancy rates should slowly decline. More baby steps toward the eventual bottom.

Caution: the above signs are very tentative.

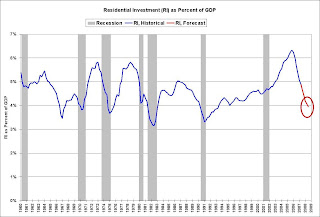

Residential Investment as a percent of GDP

The final graph shows historical RI as a percent of GDP (blue) and a rough forecast (red). My current view is that RI will bottom in 2008 (red circle).

Just as we watched housing as a leading indicator for the economy on the downside, we should also watch investment in housing as an indicator that the economy is bottoming and starting to recover. (I'll post my view on the overall economy this week).

Note: although I expect housing to bottom in '08 by these measures, I don't expect a quick rebound in housing investment.

To repeat: I expect housing to be crushed in the coming months. But it might be time to start looking ahead to the bottom in residential investment.

Sunday Morning Reflections

by Anonymous on 8/19/2007 08:58:00 AM

I did a post yesterday that was ostensibly about loan modifications, but that was trying to make that an excuse to reflect on risk/behavior modeling. It didn't work, but life is like that in the risk business.

One of my points is that while all modeling of borrower behavior can be fraught with conceptual, mathematical, and data problems, modeling of what I call the "residual" borrower and the less polite call the "woodhead" borrower is more fraught than any other part of this. In any sufficiently large group of mortgage loans, you will get a "tail" of borrowers whose behavior you cannot predict or "solve for" (as the case may be) with intelligible results.

Some people simply will not behave the way theory says they will. As a risk manager in a financial instutition, I have always had some trouble dealing with this group. As a person, of course, I have always sought them out first in bars and parties. Theory predicts that I would be making you guys pay $100 an hour to listen to my insights about the world. In the real world, I'm bloggin'. Solve for that.

I suspect some of the friction that arises from time to time in our comment section involves the fact that I don't always like best the people I prefer to lend money to. I don't even always morally approve of them. But my job has always been to lend money safely and soundly at a reasonable profit, not to dole out rewards for good behavior or use loan commitment letters as a kind of Good Housekeeping Seal of Approval, a weird sort of Calvinist-banker thing that involves identification of The Elect. It's possible that uptight cheese-paring pompous authoritarian self-satisfied literal-minded parochial nosey-parkers are overrepresented in my approved borrower pool. That doesn't mean I'm willing to live in your neighborhood, listen to your homilies, or even drink your beer.

Some of the people I love best want to buy homes because if they own it, instead of renting it, they can paint it purple if they want to. Then they do, DIY, too, because they're frugal. Often the neighbors have a big meltdown over this, because it "brings down property values."

So many people want to be not just their own landlord, but everyone else's, too. I have a very vivid memory of the first time I saw the covenants and restrictions on a new PUD somebody actually wanted to buy a (bland, featureless, identical, not purple) home in. It prohibited hanging laundry in the backyard on a clothesline. I have been an apartment-dweller for a long time, and one of the two or three idle thoughts that would occasionally get me thinking about buying a home was wanting a place to hang my sheets out in the sun. I concluded that if we were going to make homeownership the equivalent of taking a shower with a raincoat on, I'd save myself the time and money.

At some level, the argument that a mortgage servicer should try reasonable alternatives to foreclosure because to flood the neighborhood with vacant REO punishes all the innocent bystanders makes some sense. At another level, it makes me uneasy. This is probably because I am a former lit major with an active imagination instead of a real high-class math wiz who understands only standard deviations. But I keep wondering whether some of these folks would be in such dire financial straits if they hung their laundry out to dry: the sun's free, but a gas dryer isn't. Lawns that look like lawns, not putting greens, cost less to maintain. Front doors that are an out-of-fashion color are in the sale bin at HomeDepot. Do you really want your neighbors to act prudently? Do you?

When I was in grad school I lived a few doors down from some folks who drove a '63 Plymouth Fury, gold-and-primer, with "Neighbors From Hell" painted on the side with Rustoleum. They'd get their shovels out and come help me dig my innocent white Volkswagen out of a snow drift when the need arose. It was a curious kind of hell they were from.

Yves over at naked capitalism has an interesting post up this morning on "cognitive bias" and risk assessment. This paper has some interesting comments on the subject for those of you who are more analytically rigorous than I'm in the mood to be this morning. I was, I admit, taken by the discussion of hindsight bias. It may be relevant to our preoccupations. I may either take it out on the patio to read over a cup of coffee, or get out a can of spray paint and go after my car. Some days it's a knife-edge.

Foreclosure and Bankruptcy

by Calculated Risk on 8/19/2007 02:49:00 AM

From the NY Times: Loan by Loan, the Making of a Credit Squeeze. Here is an excerpt on the bankruptcy laws:

Congress is looking hard at changing the bankruptcy law so courts can restructure home loans as they do other personal loans like credit card debt. The goal, proponents say, would be to update the bankruptcy code in line with realities of the modern mortgage market.

In Chapter 13, a borrower’s mortgage obligation remains intact. The most that a person gets is extra time to catch up on payments in arrears, but every nickel on the mortgage must be paid.

The bankruptcy code went through a major revision two years ago, in what was seen as a triumph for banks and other lenders. The revision made it harder for people to declare bankruptcy, especially a Chapter 7, or “straight bankruptcy,” in which everything is liquidated, by setting tighter income and means tests to qualify. The 2005 amendments also set more stringent rules for writing down unsecured debt, notably credit card debt.

PROTECTION for the mortgage lender has been unchanged since the Bankruptcy Reform Act of 1978. At the time, first-time home buyers paid about 20 percent of the value of the houses upfront, got fixed-rate mortgages, and the lenders were local bankers — serious, skeptical types who scrutinized borrowers. Homeowners agreed to mortgages they could afford. When they ran into financial troubles, it was typically because of some unforeseen event in their lives like the loss of a job, an illness or a divorce. The mortgage was rarely the problem.

Yet the mortgage often is the financial culprit these days. That is particularly true of lending in the subprime market of zero-down loans with terms fixed for two years and then floating rates, arranged by aggressive national mortgage brokers and bankers who earn lucrative fees.

“The bankruptcy law was written for a different world, and we want to give the bankruptcy courts, and creditors, more flexible tools to work with borrowers to save their homes,” said Senator Richard J. Durbin of Illinois.

In September, Mr. Durbin, the Democratic whip, plans to propose amendments to the bankruptcy code, in a bill called the Helping Families Avoid Foreclosure Act. It would, among other things, permit writing down loans and stretching out payment terms.

Some bankruptcy experts agree that it is time to change the law. “Our bankruptcy laws are not well designed to deal with a massive wave of mortgage foreclosures,” said Elizabeth Warren, a professor at the Harvard Law School. In particular, Ms. Warren said, bankruptcy courts should be able to rewrite mortgages in line with market conditions.

The banking industry, which pushed hard for the tougher bankruptcy law in 2005, wants no easing up now.

Saturday, August 18, 2007

Neutron Loans: 'Kill people, Leave Vacant Houses'

by Calculated Risk on 8/18/2007 06:38:00 PM

From the NYTimes: How Missed Signs Contributed to a Mortgage Meltdown. Here is the quote of the day:

“All of the old-timers knew that subprime mortgages were what we called neutron loans — they killed the people and left the houses,” said Louis S. Barnes, 58, a partner at Boulder West, a mortgage banking firm in Lafayette, Colo.

Saturday Rock Blogging

by Anonymous on 8/18/2007 01:00:00 PM

This is basically just the result of a "random play" move I made the other day. For some reason the tune's been sticking with me. Apologies for the video, but maybe it'll calm everyone's nerves.

Enjoy.

Modifications and Adverse Self-Selection

by Anonymous on 8/18/2007 12:56:00 PM

What was interesting about the Lehman analysis is that it looked quite squarely at the possibility of what it calls the “moral hazard borrower,” or some set of borrowers ending up getting a mod when they wouldn’t have defaulted (or could have gotten a market-rate refi) because the servicer’s “targeting” was too wide. They conclude, actually, that with careful enough cost-to-trust analysis of the terms offered on all mods, and limiting mods to borrowers who have already become delinquent, the “moral hazard borrower” problem isn’t likely to cause noticeable losses.

If I get permission from Lehman I’ll post some more of the analysis. Until then I think I can get away with this snippet regarding the methodology of their analysis, which I bring up for discussion purposes:

In our scenario, we assumed that the proportion of the borrower pool in each of these groups [current borrowers, those who can be cured with a mod, those who cannot be cured, the “moral hazard borrower”] depends on the amount of rate or payment reduction. Because we did not have data on borrower responsiveness to loan modifications, we extrapolated the sensitivity of defaults from observed response of subprime ARMs to payment shocks. A 9% payment shock on subprime ARMs has historically caused about a 20% increase in the credit default rate (CDR). The experience from payment shocks is not entirely applicable to the loan modification scenario as subprime ARM borrowers who choose to stay on with their mortgage post-reset are adversely self-selected. The higher default rates from this self-selection cannot be directly distinguished from the economic impact of the payment shock. However, given the lack of data on the likely impact of loan modification, we are using the response to payment shocks as a proxy for the impact of loan modifications.

What might it mean to say that “borrowers who choose to stay on with their mortgage post-reset are adversely self-selected”?

First, we must assume that a choice is a choice. We therefore assume that there are alternatives, such as a refinance at a rate/payment lower than the reset rate/payment that these borrowers could qualify for but choose not to, or that the property could be sold without financial hardship to the borrower, or the borrower could simply mail in the keys.

Any borrower who “chooses” to keep a loan with a 6.50% margin that resets every six months instead of refinancing or selling at break-even or walking away is, therefore, presumed to be:

1. Uninformed

2. Irrational

3. Masochistic

4. Making plans to scarper

5. Running a tax dodge

6. So traumatized by the original experience with a loan broker that he or she is unable to contemplate going through that again even if it means starving

7. A couple of tranches short of a full six-pack, if you know what we mean.

The inescapable conclusion (you might want to sit down for this, it’s stunning) is that it is very difficult to model the behavior of this group with the usual variables like “in the money rate incentives” or “moral hazard” or “damage to credit rating” or “pupil dilation in presence of bright lights.”

At this point, we merely pause to recognize the nature of what this is saying about the subprime 2/28 and 3/27 ARM: it was never intended to be a 30-year loan. It was always a bridge loan pretending to be a 30-year loan. It cannot be modeled as a 30-year loan. But hey! It’s a great product for achieving stable homeownership goals!

In any event, as of today we’re well past that point where “choice” and “self-selection” are the operative mechanisms. In the current environment, we have:

1. Little available refinance money (lenders are not lending)

2. Little available refinance incentive (refi rates are high when they are available)

3. Little available refinance flexibility on high LTVs (the “add-on” cost for a high-LTV loan is no longer artificially lowered by “nontraditional loan products” manipulating the payment)

4. Little opportunity to sell for at least the loan amount plus transaction costs

This means, as far as I’m concerned, that it is quite likely that the universe of “post-reset borrowers” is no longer adversely self-selected. It may well be adversely selected: “little opportunity” to sell or refi does not mean “no opportunity,” and so the very highest-quality borrowers and the properties in the healthiest RE markets will opt out of the pool. But your remaining pool is not the “classic” self-selected group any longer.

This is why workout options like mods start to make sense: the pool of defaulting borrowers is no longer exclusively the group of people for whom little can be done; the pool includes people for whom the credit crunch removed what could have been a viable option. In a credit crunch, the model that assumed “adverse self-selection” no longer works reliably.

Beyond The Great Modification Controversy, I think it’s worthwhile to return to this question of how much “historical” data we ever had to justify all the risk we put into the system during the great lending bubble. A lot of people cheerfully made these 2/28s because they based their “stress test scenarios” on past episodes of economic or housing market distress in which different products were offered to borrowers (either fixed rate loans or straight “bullet” ARMs that don’t have this initial teaser/IO fixed period/prepayment penalty combo). The only excuse for this, which is now becoming explicit, is that we just counted on easy refi money and endless HPA to take care of the problem. I know that’s not news to the Calculated Risk crowd, but it still seems to be news to these CEOs (ahem) who stand up and say “no one saw this coming” and “we didn’t lend on appraised values.”

Sentinel files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy

by Calculated Risk on 8/18/2007 01:15:00 AM

From Reuters: Sentinel files for Chapter 11 bankruptcy

Sentinel Management Group Inc., a U.S. futures commission merchant whose decision to freeze client accounts on Tuesday helped roil global financial markets, filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection late on Friday.Here is the Bloomberg article with more details.

The cash management company, which managed about $1.6 billion of assets, said its board decided it was in "the best interests of the corporation, its creditors and other interested parties that a voluntary petition be filed ... in an effort to restructure the indebtedness of the corporation," according to a filing in the bankruptcy court for the Northern District of Illinois.

Fannie Mae Predicts Price Decline Will Accelerate in '08

by Calculated Risk on 8/18/2007 12:50:00 AM

WaPo: Fannie Mae Predicts Price Decline Will Accelerate in '08

Fannie Mae, the mortgage finance giant, yesterday predicted that housing prices will decline by 2 percent on average this year and by 4 percent next year as mortgage delinquencies rise, lenders tighten borrowing standards and the volume of unsold homes approaches record levels.A 2% price decline nationwide - as measured by OFHEO - sounds about right for 2007. I also expect the pace of price declines to increase next year.

"This is clearly a market poised for more severe overall credit losses," Enrico Dallavecchia, Fannie Mae's chief risk officer, said in a conference call with investment analysts.

Adding to the trouble, Dallavecchia said, is that many borrowers with adjustable-rate mortgages are facing rising monthly payments, which could drive them into foreclosure. "This could have a cascading effect in the market," he said.

Friday, August 17, 2007

Fed to Banks: Please Use Discount Window

by Calculated Risk on 8/17/2007 08:09:00 PM

From the WSJ: Using Discount Window Is Sign of Strength, Fed Says

... the Federal Reserve held a conference call with major banks to encourage them to consider borrowing from the central bank’s discount window.

... Fed officials know the discount window action will only be effective if banks either use it, or the knowledge of its availability, to expand their own lending to high-quality counterparties such as high quality mortgage borrowers.

The participants from the banking world included ABN AMRO; Bank of America; The Bank of New York Mellon; The Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, Ltd.; The Bear Stearns Companies Inc.; Citigroup; Deutsche Bank Group; Goldman Sachs; JPMorgan Chase & Co.; Lehman Brothers; Merrill Lynch; Morgan Stanley; UBS; U.S. Bank; Wachovia; and Wells Fargo.

Krugman: Workouts, Not Bailouts

by Calculated Risk on 8/17/2007 04:08:00 PM

From Paul Krugman: Workouts, Not Bailouts. Excerpts are from Economist's View.

... if historical relationships are any guide, home prices are still way too high. The housing slump will probably be with us for years, not months.And Krugman argues for workouts, not bailouts:

Meanwhile, it’s becoming clear that the mortgage problem is anything but contained. ... Many on Wall Street are clamoring for a bailout — for Fannie Mae or the Federal Reserve or someone to step in and buy mortgage-backed securities from troubled hedge funds. But that would be like having the taxpayers bail out Enron or WorldCom when they went bust — it would be saving bad actors from the consequences of their misdeeds.

Consider a borrower who can’t meet his or her mortgage payments and is facing foreclosure. In the past, ... the bank that made the loan would often have been willing to offer a workout, modifying the loan’s terms to make it affordable, because what the borrower was able to pay would be worth more to the bank than its incurring the costs of foreclosure and trying to resell the home. That would have been especially likely in the face of a depressed housing market.Tanta has written about the servicer issues. For an overview of how servicing works, see: Mortgage Servicing.

Today, however, the ... mortgage was bundled with others and sold to investment banks, who in turn sliced and diced the claims to produce artificial assets ... And the result is that there’s nobody to deal with.

...

The federal government shouldn’t be providing bailouts, but it should be helping to arrange workouts. ... Say no to bailouts — but let’s help borrowers work things out.

Tanta also wrote about some of the servicer vs. investor conflicts in SFAS 140: Like A Bridge Over Troubled Bong Water. Tanta concluded:

The time to have gotten fired up about the real issues around off balance sheet securitization--the great "de-linking" of risk that was openly advertised as the benefit to the investor of all of this--was back when those 2/28s were being originated. We here at Calculated Risk were on it back then, and being dismissed as "bubbleheads." Absolutely nobody, as far as I know, is happy with any of the bad choices we now have since we've gone into cleanup mode. But this desperate attempt to keep the moral hazard in place, whether it's Cramer begging for a rate cut or bond investors demanding that FASB shoot the wounded, sink the lifeboats, and close the gates of mercy to protect the interests of the AAA crowd, is a little hard to take.Perhaps Krugman is proposing something 'sane and useful'.

Sit down, boys and girls. There has always been an "information asymmetry" issue with mortgage-backeds. The originator has always known more than you know. The servicer has always known more than you know. The auditors have always known more about the balance sheet ingredients than you have. This problem did not arise a couple of months ago when the ABX tanked.

It has also always been the case that the party on the other side of that cash-flow is Joe and Jane Homeowner. Taxpayer, voter, citizen, parent, child, grannie and gramps, your neighbor. This is a group of folks it's a bit hard to demonize. We've been trying, with this "it's all subprime and all subprime borrowers are deadbeats" meme, but except for a few dead-ender holdouts, that dog is no longer barking. No one will be less surprised than I to find many politicians doing the wrong thing here, out of a misguided sense that something must be done, and seen to be done. Possibly someone will do something sane and useful.

UPDATE: Here is an example of bad ideas from Senator Schumer yesterday.

Senator Charles E. Schumer today renewed his call on the Bush administration to immediately lift the portfolio cap on Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to help ease the liquidity concerns in the mortgage markets. Schumer added that if Fannie and Freddie’s regulator doesn’t act soon to temporarily allow the companies to provide more liquidity, he will introduce legislation to do so as soon as Congress reconvenes in early September.

Bail Out Countrywide!

by Anonymous on 8/17/2007 01:23:00 PM

Or mortgage brokers will get like totally bummed out.

CHICAGO (MarketWatch) -- There's more at stake in Countrywide's health than the future of the company -- if it isn't able to keep making loans, the psychological impact of the loss would be felt directly by consumers, participants in a California Association of Mortgage Brokers news conference said on Thursday.

"The consumer will feel that there is no loan availability if companies like Countrywide can't keep their doors open. This isn't some small company that decided to start up yesterday that had a risky business plan. This is America's leading lender," said Ed Craine, the public relations chairman of the group.

"The credit crunch is working its way through the whole market, taking companies we've seen as solid companies that nobody would ever expect to have problems and putting them on the brink of disaster."

As it is, certain mortgage products have been drying up and lending guidelines have been tightened -- "changing almost hourly," as the California group said in a news release. Lenders who have shut their doors this year have also reduced consumer options.

The problems Countrywide is having are proof of the depth of the market's current troubles, said John Marcell, who served as the group's president from 2005 to 2006.

"It just goes to show you the state that the market is in right now when you have the largest mortgage lender in the United States having these kind of difficulties," Marcell said. "We're going to have to get some relief some place to keep companies like this still in business."

Bank Run on CFC

by Calculated Risk on 8/17/2007 11:07:00 AM

Perhaps the Fed was trying to provide liquidity to CFC.

From the LA Times: Worried about the stability of mortgage giant Countrywide Financial, depositors crowd branches.

Anxious customers jammed the phone lines and website of Countrywide Bank and crowded its branch offices to pull out their savings because of concerns about the financial problems of the mortgage lender that owns the bank.

...

At Countrywide Bank offices, in a scene rare since the U.S. savings-and-loan crisis ended in the early '90s, so many people showed up to take out some or all of their money that in some cases they had to leave their names.

Fed Emergency 50 basis point reduction in the primary credit rate

by Calculated Risk on 8/17/2007 10:11:00 AM

From the Fed:

Financial market conditions have deteriorated, and tighter credit conditions and increased uncertainty have the potential to restrain economic growth going forward. In these circumstances, although recent data suggest that the economy has continued to expand at a moderate pace, the Federal Open Market Committee judges that the downside risks to growth have increased appreciably. The Committee is monitoring the situation and is prepared to act as needed to mitigate the adverse effects on the economy arising from the disruptions in financial markets.And more:

To promote the restoration of orderly conditions in financial markets, the Federal Reserve Board approved temporary changes to its primary credit discount window facility. The Board approved a 50 basis point reduction in the primary credit rate to 5-3/4 percent, to narrow the spread between the primary credit rate and the Federal Open Market Committee's target federal funds rate to 50 basis points. The Board is also announcing a change to the Reserve Banks' usual practices to allow the provision of term financing for as long as 30 days, renewable by the borrower. These changes will remain in place until the Federal Reserve determines that market liquidity has improved materially. These changes are designed to provide depositories with greater assurance about the cost and availability of funding. The Federal Reserve will continue to accept a broad range of collateral for discount window loans, including home mortgages and related assets. Existing collateral margins will be maintained. In taking this action, the Board approved the requests submitted by the Boards of Directors of the Federal Reserve Banks of New York and San Francisco.From the WSJ: Explaining the Discount Window

The discount window is a channel for banks and thrifts to borrow directly from the Fed rather than in the markets. ... A few years ago the Fed overhauled the discount window ... the rate was then set one percentage point above the funds rate and subject to far fewer conditions. ... discount window borrowing has remained paltry. Discount lending averaged just $11 million in the week ended Aug. 15. Although that was up from $1 million in the prior week it was puny compared to the billions of dollars the Fed has regularly injected into the financial system through open market operations.

Fed officials hope that reducing the penalty rate associated with the window and lengthening the term of loans to 30 days from one ... and gives it a tool to supplement open market operations for reliquefying markets. ... The discount window however is available to any bank or thrift, and the terms are easier than for fed funds loans. For example, banks may submit mortgage loans, including subprime loans that aren’t impaired, as collateral, and many probably will.

Lookback-ward, Angel

by Anonymous on 8/17/2007 07:45:00 AM

The question of falling yields on the low end of the curve and ARM resets comes up periodically in the comments. I offer a few UberNerdly tidbits of information about that.

First, review: an ARM adjusts to a rate equal to index plus margin. The index used and the margin, expressed as points, are spelled out in the note, as is the “reset” date. Your note will call this a “Change Date.” There are rate Change Dates and payment Change Dates. In an amortizing or interest-only loan, the payment changes on the first day of the month following the rate change. (Interest is paid in arrears on a mortgage loan.)

The index used will have a “maturity” equivalent to the frequency of the rate adjustments once the loan gets past its initial fixed period (if it has one). A true 3/1 ARM will adjust every year after the first three years, and so it will be indexed to some kind of 12-month money. The 2/28 and 3/27 are so-called to distinguish them from a 2/1 and 3/1; the 2/28s reset every six months after the first two years, not every year thereafter. (This convention is not consistent across the industry, I’m afraid. There are many, many Alt-As out there labeled as 5/1s that are really 5/25s.)

The “traditional” ARM was indexed to constant-maturity Treasuries (CMT). Almost all ARMs with a 6-month reset are indexed to LIBOR, but plenty of loans these days with a 1-year reset are indexed to LIBOR. LIBOR comes in 6-month and 12-month versions, just like Treasuries.

So the note for a 2/28 will say that the new interest rate will be equal to the 6-month LIBOR value plus the margin, usually rounded to the nearest eighth, subject to the adjustment caps, as of a certain date. Most 2/28s have caps you will see indicated as “2/1/6.” That means that the rate cannot go up or down more than 2.00 points at the first adjustment; it cannot go up or down more than 1.00 point at any adjustment after the first one; and it cannot go up more than 6.00 points over the life of the loan. (Unless you’re dealing with a real slimy lender who puts a “floor” on your ARM, so that it cannot go up or down more than 6.00 points over its lifetime. That’s all too common in subprime, but not in Alt-A or prime. The GSEs will not allow “floors” on an ARM: the rate can go down as far as the formula index plus margin can go down.)

The note will also indicate the time that the new index value is established. This is called a “lookback period,” although you will not see the term “lookback” in your note. All ARMs indexed to the one-year Treasury, and some other ARMs, will have a 45-day lookback period, which means that the new index value will be “the most recent index figure available as of the date 45 days before each Change Date.” This 45-day period was established as “standard” back in the old days, when lenders got information about indices from statistical releases published by the Fed on paper and sent out in snail mail; the servicer often didn’t have the “most recent” index value until some point in the month prior to that Change Date, which occurs on the first. But to keep things uniform and fair to the borrower, the value was the one in effect 45 days prior to the change, even if the lender didn’t get that info until two weeks before the change, when it could start updating its index tables on its servicing system (or having Marge in servicing get out the ledger book and a sharp pencil).

Almost all ARMs with a LIBOR index, on the other hand, have a “first business day” lookback. That means that the index value used is “the most recent value as of the first business day of the month immediately preceding the month in which the change occurs.” These notes specify that the source of the LIBOR index is the Wall Street Journal; there wasn’t much of a time delay in getting the WSJ for servicers even back before the internet.

So anybody with an annually-adjusting ARM with a reset date of October 1 will have gotten the August 15 index value. Anybody with a semi-annual ARM (like a 2/28) will get the index value in effect on September 3. In both of those cases the new payment at the adjusted rate will start on November 1.

Margins on prime ARMs are usually 2.75 for Treasury ARMs and 2.50-2.75 for LIBORs. Alt-A is generally 2.75-3.50 or thereabouts; the “risk-based pricing” adjustments will vary by the amount of risk-layering on the loan. Subprime can range from 3.50 to 6.50, again depending on loan quality and other terms.

A 2/28 with a start rate of 8.50% that has its first adjustment on September 1 and a margin of 6.50% will have a “fully-indexed” value of 11.82688 (6 Month WSJ LIBOR on 8/1/07 = 5.32688). Rounded to the nearest eighth that’s 11.875%. Since that is more than the maximum first adjustment cap of 2.00% allows, the rate adjusts to 10.50%. At the next 6-month adjustment, it can go up another 1.00 point. It does not stop going up unless and until it hits a fully-indexed rate of 14.50%, which is the lifetime cap (start rate plus 6.00%).

A lot of the modifications that are going on right now involve servicers taking a look at that 6.50% margin. If, in fact, the borrower did make the first 24 payments on time, there’s an argument to be made that that margin could come down to something closer to Alt-A or near-prime. If you modified the note to bring the margin on the example loan above down to 3.50%, you’d get the rate resetting to 8.875% instead of 10.50%. On a $100,000 loan, that would be a payment of $807.49 versus $924.50. If you made that modification subject to future modification back to 6.50% if the borrower doesn’t perform, you are, possibly, offering an incentive for continued performance. And if the borrower continues to perform, it’s hard to understand why you’d still call it “subprime.” Credit grades are snapshots in time, not prisoner tattoos.

“Normally,” of course, people who take subprime loans and manage to perform for at least 24 months are supposed to refi into a nice cheap prime loan. Now that LTVs are just too high for that, some people are going to have to stay in the loan they’re in. There may only be a few subprime borrowers who fit this case—who have made the first 24 payments on time, can handle an adjustment from 8.50% to 8.875%, and want to continue to own the home—but I’m damned if I can see why we shouldn’t do margin-mods for those few. 350 bps is a fair margin over credit risk-free money for someone who is making the payment every month. Sure, it might mess up your excess spread calculations on your ABS, but foreclosing will mess it up worse.

That said, please note that we’d have to have a miraculous LIBOR rally to help out anyone with a 6.50% margin and an 8.50% start rate: the 6-month LIBOR would have to hit 2.00% on the first business day of the month before the reset date to keep that loan flat. Those nasty neg am ARMs with rates that reset monthly, based on a monthly index, might get some short-term slowing in the rate of negative amortization, but it’ll take a long, long stretch of low short rates to bail those things out.

Thursday, August 16, 2007

Will U.S. Woes Hit Global Growth?

by Calculated Risk on 8/16/2007 10:44:00 PM

From the WSJ: Markets Fear U.S. Woes Will Hit Global Growth

"Today is the first day that markets are asking questions as to whether global growth is going to be significantly affected," said Jim O'Neill, head of global economic research at Goldman Sachs. "Today feels quite scary, frankly."This is a key question. I started the year arguing that housing would lead to a U.S. slowdown, and also a lower trade deficit as imports slowed, eventually slowing growth in exporting companies, and leading to a global slowdown. I'll have more on this possibility tomorrow.

It was only three weeks ago that the International Monetary Fund raised its outlook for global economic growth this year and next. While the IMF acknowledged that U.S. growth would fall short of its earlier forecasts, it predicted that fast-rising China and India, helped by a cyclical upswing in Japan and Europe, would more than pick up the slack.

The scenario that worries investors around the world starts with a U.S. slowdown set off by lower housing prices and tougher lending standards. That would lead the U.S. to import fewer computers, cars and sneakers, hurting big exporters such as China and South Korea.

Those countries have been big buyers of commodities, driving up the prices of oil and metals. If they eased back, that would hurt big commodity producers such as Brazil and put some large, risky commodity ventures around the world at risk.

Mohamed El-Erian, head of the company that invests Harvard University's $29 billion endowment, believes the more-optimistic picture of global growth still has merit -- as long as the U.S. economic slowdown is gradual and doesn't result in a recession. "The next few weeks will be a test of this thesis," he said.

30 Year Mortgage Rates and Ten Year Treasury Yield

by Calculated Risk on 8/16/2007 06:51:00 PM

Freddie Mac reports that mortgages rates were up slightly during the last week:

Freddie Mac today [said] the 30-year fixed-rate mortgage (FRM) averaged 6.62 percent with an average 0.4 point for the week ending August 16, 2007, up from last week when it averaged 6.59. Last year at this time, the 30-year FRM averaged 6.52 percent.

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.Here is a scatter graph showing the 30 year fixed rate mortgage (Freddie Mac average monthly rate) vs. the monthly Ten Year treasury yield for every month since Jan 1987 (last 20 years).

The grey blocks are pre-2001 (before the Fed started aggressively cutting rates). The light blue blocks are after Jan 2001. The Red block is this week.

It appears 30 year rates for prime conforming fixed-rate mortgages are still within the normal range when compared to 10 year treasury yields. The graph might tell a very different story for jumbo prime loans, or non-prime loans, but I don't have the data for jumbos.

Note: This shows rates are still low compared to the last 20 years. Rates were even higher in the late '70s and early '80s. Mortgage rates in '50s and '60s were on the low end of the scale, but Freddie Mac doesn't provide any data for those periods.

Moody's downgrades 691 mortgage-backed securities

by Calculated Risk on 8/16/2007 06:19:00 PM

From MarketWatch: Moody's downgrades 691 mortgage-backed securities

Moody's Investors Service said on Thursday that it downgraded 691 mortgage-backed securities because of "dramatically poor overall performance." These residential mortgage securities were originated in 2006 and backed by closed-end, second-lien home loans, Moody's said. ... The downgraded securities had an original face value of $19.4 billion, representing 76% of the dollar volume of securities rated by Moody's in 2006 that were backed by subprime closed-end second lien loans ... "The actions reflect the extremely poor performance of closed-end second lien subprime mortgage loans securitized in 2006," Moody's said. "These loans are defaulting at a rate materially higher than original expectations."