by Calculated Risk on 9/09/2008 02:11:00 PM

Tuesday, September 09, 2008

S&P: Lehman on CreditWatch with Negative Implications

From S&P (no link):

Standard & Poor's Ratings Services said today that it placed ... Lehman Brothers ... on CreditWatch with negative implications.Meanwhile Lehman stock is off 36% right now. (WaMu off 24%)

"The CreditWatch listing stems from heightened uncertainty about Lehman's ability to raise additional capital, based on the precipitous decline in its share price in recent days," said Standard & Poor's credit analyst Scott Sprinzen. "Although the ratings ultimately could be affirmed, we do not currently rule out the possibility of lowering the ratings by more than one notch."

The Budget Disaster

by Calculated Risk on 9/09/2008 12:13:00 PM

From MarketWatch: Federal budget deficit to remain near $400 billion, CBO says

With the economy weakening and spending on the war rising, the federal government's budget deficit is expected to more than double this year compared with last year, the Congressional Budget Office estimated Tuesday. The federal deficit is projected to hit $407 billion in the fiscal year that ends Sept. 30 ...The assumptions in the CBO report are very optimistic, and the structural budget deficit will likely be worse than their forecast.

Also, to be accurate, this is the Unified Budget deficit. The General Fund deficit (the responsibility of the President) will be over $600 billion this year. This will put the National Debt close to $10 Trillion when the next President takes office in January 2009 (not counting any impact from the Paulson Plan for Fannie and Freddie).

What ever happened to that Joshua B. Bolten guy? (Yes, I know he is now Chief of Staff). Bolten kept telling us the budget deficit would be cut in half by the time President Bush left office.

We have arrived at this point largely because of this President’s and this Congress’ pro-growth policies, especially tax relief. Those policies have strengthened the economy, which is now producing better-than-expected tax revenues.That statement was never accurate. Tax revenues increased in 2005 primarily because of the housing and credit bubble, and the improvement was a short term illusion. Now we are left with a massive structural budget deficit.

Joshua B. Bolten, July 2005

Note: there are many misconceptions about the budget and the National debt; too many to cover in this short post. But here are three key points:

If we are serious about the issues, the fiscal discussions should focus on health care and the General Fund deficit.

This budget disaster was very foreseeable, but we wouldn't know that listening to Grenspan in 2001 or Bolten in 2005.

Lehman, WaMu Cliff Diving

by Calculated Risk on 9/09/2008 11:19:00 AM

Consider this an open thread.

Lehman is off 32%. MarketWatch reports talks between LEH and Korea Development Bank have ended.

WaMu is off 20%. Reuters reports: WaMu debt protection costs hit record-Markit

Freddie Mac and the "Two Year Rule"

by Anonymous on 9/09/2008 10:53:00 AM

People keep sending me this article or bringing up this "fact" in the comments. Because it is such a fine example of a "fact" that isn't actually a fact, but is apparently becoming an article of quasi-religious faith in some quarters, I shall make the attempt to slap it down. I have no particular illusions about how well this will work, but there may be a handful of people who actually care about accuracy and good faith, even (!) when the subject is Freddie Mac. I'm talkin' to you.

*********************

Let me start out with a couple of general observations. This post is about financial accounting matters. If you are one of those people who drove us insane in the comments to yesterday's post on "assets" versus "liabilities" by arguing that "assets" are "really" "liabilities" because you, like Humpty Dumpty, are The Master, then you will find this post unsatisfactory. Tell it to the Marines. The habit of refusing to use standard accounting terms in preference to sloppy "synonyms" is what got these two reporters in trouble in the first place. I'm not going to pander to anyone by doing it myself.

Second, we basically went through a nearly identical version of this brouhaha last November with Fannie Mae. It's deja-vu all over again.

The offending "fact" comes from this article by the world-renowned Gretchen Morgenson and Charles Duhigg, whose willingness to believe anything any unnamed source says about Freddie Mac, whether it makes sense or not, has been documented before on this blog.Finally, regulators are concerned that the companies may have mischaracterized their financial health by relaxing their accounting policies on losses, according to people familiar with the review. For years, both companies have effectively recognized losses whenever payments on a loan are 90 days past due. But, in recent months, the companies said they would wait until payments were two years late. As a result, tens of thousands of loans have not been marked down in value.

What follows is my best effort to discover what the hell these people are talking about. I must disclose to you all that I am really just making an educated guess here. If you possess any expertise at all in financial accounting in general and Freddie Mac's business operations in particular, the foregoing paragraphs do not make any sense whatsoever. (It's like talking to people for whom "asset" "really" means "liability.") So I could be wrong, and they could be talking about some entirely different part of the balance sheet. Anyone with a better guess than mine is hereby invited to share.

The companies have injected their own capital into pools of securities containing these loans, arguing that their new policies are helping more borrowers. Under conservative accounting methods, changing these policies would not have any impact on the companies' books. However, people briefed on the accounting inquiry said that Freddie Mac may have delayed losses with the change.

My theory is that they are talking about optional repurchases of MBS loans. I cannot think of or find any other part of Freddie's financial statements in which that "two-year rule" or this thing about "injecting capital" would fit. And if they are talking about optional repurchases, they're guilty of terrible reporting. Either their sources are badly informed or they didn't understand what their sources told them or both.

To review the basics of what Freddie does: they buy mortgage loans on the secondary market. These purchases of loans result in two different "portfolios" of loans: the "retained portfolio" and the "guarantee portfolio." The retained portfolio consists of loans and MBS that are owned outright by Freddie. That means Freddie's capital is invested in these loans. Freddie gets the capital to invest in the retained portfolio in large part by issuing notes and bonds--what everyone calls "agency debt." The retained portfolio constitutes an "asset" on Freddie Mac's books (net of the loss reserves), and the debt-funding constitutes a "liability" thereon.

The "guarantee portfolio" consists of various MBS that Freddie guarantees the credit risk of, but does not invest the capital in. The capital to fund these securities is provided by investors who buy MBS. Therefore, the total principal amount of the guarantee portfolio is not an asset on Freddie's books (it is an asset on the MBS investors' books). What shows up on Freddie's balance sheet is the "guarantee asset," which is the fair value of the guarantee fees received, and the "guarantee obligation" (over on the liability side) which reflects the fair value of the projected credit losses.

This distinction between retained and guaranteed portfolios is one reason why Freddie's (and Fannie's) financial statements are complex; each part of the "total portfolio" has different accounting treatment. If you read through these financial statements or any reports having to do with portfolio balances or loan purchase volume, you simply need to pay attention to when a number is given for the "total portfolio" versus one or the other parts thereof. To answer a question that may arise at this point, as of June 30 the principal balance of Freddie's retained portfolio was $792 billion and the guarantee portfolio balance was $1.410 trillion, making a total portfolio of $2.202 trillion (see Table 49 of the 10-K).

So. How do loans get into the retained portfolio? They are either originally purchased as portfolio investments or, in some cases, they were originally purchased in the guarantor program but had to be repurchased out of the MBS. As I said, the current flap seems to be about repurchases of MBS loans. I am going to quote here from Freddie Mac's 10-K. It will help you to know that "PC" means "Participation Certificate," and is just Freddie-speak for "MBS."We also have the right to purchase mortgages that back our PCs and Structured Securities from the underlying loan pools when they are significantly past due. This right to repurchase collateral is known as our repurchase option. Through November 2007, our general practice was to purchase the mortgage loans out of PCs after the loans became 120 days delinquent. Effective December 2007, we no longer automatically purchase loans from PC pools once they become 120 days delinquent, but rather, we purchase loans from PCs when the loans have been 120 days delinquent and (a) the loans are modified, (b) foreclosure sales occur, (c) the loans have been delinquent for 24 months or (d) the

Remember that the "guarantee" on the MBS means that Freddie Mac is responsible for passing through interest payments to bondholders as long as those bondholders have principal invested, whether the borrowers make payments or not. The way this usually works is that for the first 90 days of delinquency (120 days since last payment), the servicer is obligated to advance scheduled interest and principal to Freddie Mac, who passes it through to the bondholders. The servicer makes efforts to collect the past-due payments from the borrowers. Generally at around 90-120 days, if the loan is still delinquent, the servicer's obligation to advance payments stops and Freddie Mac is the one obligated to advance payments to the bondholders. The basic contractual terms of the MBS are that Freddie has the right, but not the obligation, to buy a seriously delinquent loan out of the pool at this point. The repurchase price would always be par, since the bondholder must receive 100% of principal invested per the terms of the guarantee. Obviously, a seriously delinquent loan is likely to have a fair value of much less than par, but Freddie has to take that loss, not the MBS investor.

cost of guarantee payments to PC holders, including advances of interest at the PC coupon, exceeds the expected cost of holding the nonperforming mortgage in our retained portfolio. Consequently, we purchased fewer impaired loans under our repurchase option for the three and six months ended June 30, 2008 as compared to the three and six months ended June 30, 2007. We record at fair value loans that we purchase in connection with our performance under our financial guarantees and record losses on loans purchased on our consolidated statements of income in order to reduce our net investment in acquired loans to their fair value.

However, that is an option, not an obligation. Alternatively, Freddie can allow a seriously delinquent loan to remain in the MBS, while continuing to advance payments to the bondholders, until foreclosure or modification, for up to two years. To my knowledge the two-year limitation has always been part of the MBS rules--it's just the outside limit on how long Freddie (same for Fannie) can keep advancing on delinquent MBS loans before they have to give up and repurchase them. There have never been many loans that are seriously delinquent for two years without ever getting to foreclosure or workout, but in the strange cases (probate, bizarre title problems) it can happen. In no sense is this "two year rule" about letting loans just stay delinquent with no action by the servicer or Freddie Mac, or no effect on the fair value of the guarantee obligation, for two years. It absolutely does not mean that no credit losses are taken until a loan is "two years late." The two years refers to how long a delinquent loan can stay in the MBS, not how many months past-due it can be before it is impaired.

Why would Freddie elect to repurchase a loan when it doesn't have to? Well, if the cost of capital is cheap, but the interest payments you have to advance to the bondholders are not, it generally makes sense to repurchase the loan. The loan balance then comes out of the "guaranteed portfolio" and into the "retained portfolio." The write-down of the asset occurs immediately, given that the purchase price of the loan was par (100% of unpaid principal balance) but the fair value of a seriously delinquent loan is less than par. So a loss is immediately recognized by the retained portfolio. On the other side of the books, the guarantee asset and obligation are adjusted to reflect the fact that this loan is no longer earning a guarantee fee or reflecting guarantee costs. Any final loss taken on the loan in foreclosure is taken on the retained portfolio side, not the guarantee side.

On the other hand, if the cost of capital--Freddie's borrowing cost, including capital reserve requirements--is expensive, but the interest payments to be advanced to bondholders are relatively cheap, then you leave the loans in the MBS unless and until you are obligated to buy them out, which would be when they are delinquent and they are modified, foreclosed, or hit that two-year limit. If the loans stay in the MBS, they rack up those costs that go into the guarantee obligation, but they do not result in a recognized loss to the retained portfolio because they are not in the retained portfolio.

Now, go back and reread the Morgenson/Duhigg version of this and see if it strikes you as a reasonable paraphrase. As you do this, ask yourself if you've read anything lately in the news about Freddie needing to increase its capital reserves and facing much higher borrowing costs than it had previously. Then ask yourself if this all might be about not "injecting capital" into "pools of securities."

Of course this election not to buy out every seriously delinquent MBS loan means that fewer losses have to be recognized in the retained portfolio. The whole damned idea is to keep these loans in the guaranteed portfolio instead of the retained portfolio. However, it certainly doesn't keep Freddie from having to pay interest to bondholders every month, whether paid by the borrower or not. It still has a major effect on credit losses. It simply keeps the loans' principal balance "financed" by MBS bondholders instead of by Freddie Mac.

Has that been a wise move by Freddie? Well, I don't know we could answer that question in Morgenson/Duhigg terms, since they seem to think that the only "losses" that can be taken are in the retained portfolio. You would have to analyze the effect of the interest advances to the guarantee side of the books to see if this was a smart move or not. But of course Morgenson and Duhigg have no intention of doing that--I suspect they fail to grasp how one might do that--because to do so interferes with the narrative of "cooking the books" that they're peddling.

The interesting question that will arise, of course, is what will happen to this repurchase policy post-conservatorship. Will the government order Freddie to start buying out every delinquent MBS loan at 90 days down--knowing that the government might have to provide the capital for them to do that--in order to book retained portfolio losses "promptly," or will it perhaps decide to let the bondholders continue to finance these loans, just as Freddie has done? I'm really looking forward to finding out, myself.

At any rate, if one more person starts bringing up this canard about "no losses until the loan is two years past due" in the comments, those of us who are actually paying attention are going to jump your case for--wittingly or not--spreading stupid. You gotta stop believing everything you read in the paper.

Pending Home Sales Index Declines

by Calculated Risk on 9/09/2008 10:04:00 AM

From the NAR: Near-Term Home Sales to Stay in Narrow Range

The Pending Home Sales Index, a forward-looking indicator based on contracts signed in July, fell 3.2 percent to 86.5 from an upwardly revised reading of 89.4 in June, which had risen 5.8 percent from May. The July index remains 6.8 percent below July 2007 when it stood at 92.8.The Pending Home Sales index leads existing home sales by about 45 days, so this suggests existing home sales in September will be off slightly.

For some graphs comparing existing home sales to pending home sales, see: Do Existing Home Sales track Pending Home Sales? The answer is yes - they do track pretty well.

Fannie, Freddie Get Special IRS Tax Rule

by Calculated Risk on 9/09/2008 09:35:00 AM

From CFO.com: Fannie, Freddie Get Tax Pass, Too (hat tip Alain)

Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson ... had the IRS issue Notice 2008-76, which essentially allows the two government-sponsored enterprises to retain all of their [net-operating losses] NOLs, despite a change of control of ownership, tax expert Robert Willens told CFO.com.Not a big deal - but another interesting aspect of the Paulson Plan.

Under the tax code — specifically Section 382 — NOLs are severely limited when there is a change of control. The rule is in place to prevent acquiring companies from buying up targets just to gain access to their NOLs. The NOLs for Fannie and Freddie are substantial. Over the last four quarters, Fannie and Freddie recorded about $14 billion in aggregate losses.

In essence, Paulson changed tax law so that the two lenders aren't paying more in taxes to the government as a result of that same government becoming their controlling investor. ...

"I am not saying that the IRS ruling is a good thing, or a bad thing, it is just unusual," asserts Willens. "Then again, this is a very unusual situation."

Monday, September 08, 2008

Bove on WaMu: Problem is Simple, Too Many Bad Loans

by Calculated Risk on 9/08/2008 09:41:00 PM

"The problem is very simple. They made a lot of bad loans and they are absorbing high levels of loan losses. The solution for their problem is to find some mechanism for reducing the bad loans. That can't be done by a new CEO."From the WSJ: WaMu Placed on Probation Amid Management Shakeup (the "probation" headline refers to the Memorandum of Understanding with the OTS)

Richard Bove, banking analyst with Ladenburg Thalmann & Co. Inc.

WaMu has $53 billion in option adjustable-rate mortgages ... Of the $53 billion in option ARMs, $14 billion of these are to the riskiest segment in mortgage lending, subprime borrowers.Bove's comments remind me of former IMF chief economist Ken Rogoff's comment last month (see the BBC: US bank 'to fail within months' )

WaMu also has $62 billion in home-equity loans ...

Mr. Bove predicts that WaMu will lose $40 billion over the next three years on its loan portfolio. If the economy weakens further and losses are even higher, he said, "the future of the company is questionable."

"We're not just going to see mid-sized banks go under in the next few months," said Mr Rogoff, who held the IMF role between 2001 and 2004.

"We're going to see a whopper, we're going to see a big one, one of the big investment banks or big banks."

Wells Fargo to take Fannie & Freddie Related Write-Down

by Calculated Risk on 9/08/2008 05:24:00 PM

From the WSJ: Wells Fargo Says It Will Take Third-Quarter Write-Down On Fannie, Freddie Holdings

Wells Fargo & Co. said ... its perpetual preferred investments in Fannie and Freddie are included in securities available for sale at a cost of $336 million and $144 million, respectively. Those securities now trade at 5% to 10% of their original value.The F&F confessional is open.

Housing: It's about prices ...

by Calculated Risk on 9/08/2008 12:56:00 PM

"Our economy and our markets will not recover until the bulk of this housing correction is behind us."So when will the "bulk of this housing correction" be behind us? Right now prices are still too high.

Treasury Secretary Hank Paulson, Sept 7, 2008

Here are a few ways to look at house prices: real prices (inflation adjusted), price-to-rent ratio, and price-to-income ratio.

The first graph compares real and nominal Case-Shiller Home Prices through Q2 2008 (real is current index adjusted using CPI less Shelter).

Click on graph for larger image in new window.

Click on graph for larger image in new window.In real terms (red line), the Case-Shiller National Home price index is off 25% from the peak. Real prices are now back to the Q4 2002 level (nominal prices are back to mid-2004).

This suggests real prices, based on the Case-Shiller index, could fall substantially, perhaps 15% to maybe even 30% more. This decline would probably be some combination of falling nominal prices and more inflation. And prices could definitely overshoot to the downside.

The second graph shows the price to rent ratio (Dec 1982 = 1.0) for both the OFHEO House Price Index and the Case-Shiller National Home Price Index. For rents, the national Owners' Equivalent Rent from the BLS is used. This graph is from this earlier post.

The second graph shows the price to rent ratio (Dec 1982 = 1.0) for both the OFHEO House Price Index and the Case-Shiller National Home Price Index. For rents, the national Owners' Equivalent Rent from the BLS is used. This graph is from this earlier post.Data is available quarterly for the Case-Shiller National Index starting in 1987. For this graph, the price-to-rent ratio for Case-Shiller in Q1 1987 was set to the OFHEO price-to-rent for Q1 1987.

Looking at the price-to-rent ratio based on the Case-Shiller index, the adjustment in the price-to-rent ratio is probably 60% complete as of Q2 2008 on a national basis. This ratio will probably continue to decline with some combination of falling prices, and perhaps, rising rents. And the ratio may overshoot too.

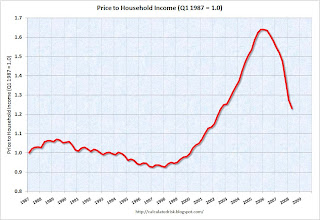

The third graph shows the price-to-income ratio and is based off the Case-Shiller index, and the Census Bureau's median income Historical Income Tables - Households.

The third graph shows the price-to-income ratio and is based off the Case-Shiller index, and the Census Bureau's median income Historical Income Tables - Households.Using national median income and house prices provides a gross overview of price-to-income (it would be better to do this analysis on a local area). However this does shows that the price-to-income is still too high, and that this ratio needs to fall another 20% or so. Once again this could be a combination of falling prices and rising incomes (Note: this uses nominal incomes, and even if real incomes are stagnate or declining, nominal incomes are rising).

So by these three measures, prices have a ways to fall.

And finally, as long as inventory levels are substantially above normal (especially inventories of distressed properties), prices will probably continue to decline. So this graph is very useful:

The final graph shows the 'months of supply' metric for existing homes for the last six years.

The final graph shows the 'months of supply' metric for existing homes for the last six years.Months of supply increased to 11.2 months. A normal range is 5 to maybe 8 months. Until the months of supply decreases to the normal range, prices will continue to fall.

How much longer will prices fall? How much further will prices decline? No one knows, but these graphs suggest we still have a ways to go.