by Anonymous on 8/30/2008 09:46:00 AM

Saturday, August 30, 2008

Why are regulators always behind?

Here's an article featuring regulators reacting to 3 to 5 year-old news.

http://www.bloomberg.com/apps/news?pid=20601068&sid=aBDDcYvIKUdE&refer=economy

I have some observations about regulators:

1. They are retstrained by Congressional inaction or mission statements.

2. They are not actively in the marketplace, so they miss the first signs of trouble. More than a year ago, a retail store owner could have told you the economy was sinking. For our small consulting firm, 9 months ago it became easier to find accounting talent. Are regulators in the Ivory Tower?

3. There are more inputs into any economic analysis than there ever were before. In the early 90's recession, Asia meant Japan, Europe was 3 countries, the Middle East was just a gas station and The Americas was the US. Now, there are so many more countries with real economies, what's the benchmark?

What can regulators do? What should they do?

SFAS 157, Fair Value and Other Fairy Tales

by Anonymous on 8/30/2008 07:39:00 AM

There’s been much discussion on various blogs about Fair Value Accounting. Proponents make an excellent point in that, what difference does it make what you paid for something? If you’re telling me, an investor, that you have a certain amount of assets on your books, prove to me what they’re worth. Not exactly a revolutionary thought to have. The fact is, this is what balance sheets have supposed to be reflecting all along. “Lower of Cost or Market” they called it back in school over the sounds of clicking abaci.

What really changed recently with SFAS 157 are the number of assets under fair value rules and the additional required disclosures, mostly footnotes, for Fair Value accounting for various instruments.

What types of assets should be subject to fair value accounting? Should a company revalue its land and equipment each year? Seems like a lot of work and expense. Corporations already keep two sets of books, GAAP and Tax. To be fair, the underlying transactions are the same for both, but the more in-depth analysis is performed by two separate groups of well paid employees, the Reporting Group and Tax Department. Fair value will involve hiring another group of accountants; perhaps not as large, but more expense.

What is the benefit? Fair Value isn’t going to mean much for internal operations. Some of the biggest opponents are US based manufacturers, headed by automakers. Does it matter what your plant’s equipment is worth? Not for internal purposes. It won’t help you analyze your business. In the case of Plant Equipment, not even the investors benefit much from fair value.

What types of assets should be valued at fair value? Most of us agree that securities are at the center. We’re now in the process of sorting out the values of nicely packaged garbage on banks’ books. Basic Economics and Accounting theory posits that assets should be valued at discounted future cash flows. Cash is the exit strategy for all assets. Nowhere is this more evident than valuing securities. With securities, we need to look at the intent of the owner; the exit strategy to convert to cash. So, the exit strategy defines the valuation method. For securities, this brings us to the three categories of investments; Levels 1, 2 and 3. Here are guidelines:

Prior Name; Available for Sale

English Translation; We’re selling if the price is right

Valuation; Market value, preferably on an exchange

Prior Name; Held to Maturity

English Translation; We’re not selling

Valuation; Cost, unless the loss is “other than temporary”.

The levels indicate how obvious or concrete the market comparisons, with L1 the highest. Do you see a trend in valuations? It’s ALL exit value. It’s all based on intent. The reason we don’t time value discount Level 1 and 2 securities is because the cash conversion is projected to happen now (or soon enough).

Side note: Temporary L2 asset losses are found further down on the Income Statement under Other Comprehensive Income (sort of purgatory place) where they do not get factored into P/E ratios.

Friday, August 29, 2008

Cartoon of the Day

by Calculated Risk on 8/29/2008 11:00:00 PM

Bank Failure: Integrity Bank, Alpharetta, Georgia

by Calculated Risk on 8/29/2008 05:27:00 PM

From the FDIC: Regions Bank Acquires All the Deposits of Integrity Bank, Alpharetta, Georgia

Integrity Bank, Alpharetta, Georgia, with $1.1 billion in total assets and $974.0 million in total deposits as of June 30, 2008, was closed today by the Georgia Department of Banking and Finance, and the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation was named receiver.One more. We will see two today?

The FDIC Board of Directors today approved the assumption of all the deposits of Integrity Bank by Regions Bank, Birmingham, Alabama. All depositors of Integrity Bank, including those with deposits in excess of the FDIC's insurance limits, will automatically become depositors of Regions Bank for the full amount of their deposits, and they will continue to have uninterrupted access to their deposits. Depositors will continue to be insured with Regions Bank so there is no need for customers to change their banking relationship to retain their deposit insurance.

...

Regions Bank has agreed to pay a total premium of 1.012 percent for the failed bank's deposits. In addition, Regions Bank will purchase approximately $34.4 million of Integrity Bank's assets, consisting of cash and cash equivalents. The FDIC will retain the remaining assets for later disposition.

...

The FDIC estimates that the cost to its Deposit Insurance Fund will be between $250 million and $350 million. Regions Bank's acquisition of all deposits was the "least costly" resolution for the FDIC's Deposit Insurance Fund compared to all alternatives because the expected losses to uninsured depositors were fully covered by the premium paid for the failed bank's franchise.

Integrity Bank is the tenth FDIC-insured bank to fail this year, and the first in Georgia since NetBank in Alpharetta on September 28, 2007.

The End is Nigh

by Anonymous on 8/29/2008 02:11:00 PM

When you're going after the "impulse depositor" market share off the sidewalk, you're in trouble.

(Thanks, Alex.)

Oil and Gustav

by Calculated Risk on 8/29/2008 01:48:00 PM

It's way too early to tell if this will be a huge story or a "nothingburger" (hopefully), but Tropical Storm Gustav is a potential threat to the GOM and oil production.

Click on image for larger image in new window.

Here are some excellent sites to track hurricanes:

National Hurricane Center

Weather Underground Note: See Jeff Master's blog.

IndyMac Mods: Principal Forbearance Vs. Reduction

by Anonymous on 8/29/2008 09:49:00 AM

Having done my share of griping about the FDIC's plan for modifying IndyMac loans, I feel obligated to point out that I didn't describe the program as fully and accurately as I might have. This is a problem I must rectify.

I'm not, apparently, the only one who missed the implications of the FDIC's use of the term "principal forbearance" in the context of this plan. An RBS research report on the potential impact of the plan for IMB securities that was published recently uses the terms "principal forbearance" and "principal reduction" interchangeably. A new JP Morgan report, however, which was recently updated and republished after someone spent some time asking the FDIC for further information (smart move), clarifies for us exactly what the FDIC means by "principal forbearance."

To remind everyone, the FDIC approach is to arrive at a total housing-payment-to-income ratio or HTI, which they confusingly call a "DTI," of 38%. This can be achieved by using one or more of the following restructuring approaches.

First, the interest rate is lowered to the current Freddie Mac survey rate for fixed rate mortgages, and fully amortized as a fixed rate loan. As far as I can tell, at this initial step, the loan is amortized over its remaining term, whatever that is.

If that is not enough to achieve 38% HTI, then the interest rate is "stepped" for up to five years. That means that the initial rate is set no lower than 3.00% for the first year, and increased each year by no more than 1.00% per year, until it hits the Freddie Mac survey rate (which was 6.50% at the time FDIC published). This does not make the loan an ARM or subject it to negative amortization; the payment is re-amortized each year after the interest rate "steps up" until it hits the permanent rate. That means that the loan is always paying some principal from the inception of the mod.

Remember that ARMs involve potential rate increases; whether they happen or not, and how far they go, depend on future (unknown) movements in the underlying index. A "step loan," which is what I understand these mods to be, has scheduled rate increases that are exactly specified in the modification agreement, and which are not subject to future market rate fluctuations: each loan will "step up" to the permanent rate, regardless of what happens in a year or four to market interest rates. So the borrower gets the same kind of long-term "rate lock" of a fixed rate loan--the rate will never be higher than 6.50% (or whatever the Freddie rate is on the day the mod is drawn up), and after the initial "step" period it will never be lower than that. The step period simply "ramps" the borrower into the fully-amortized payment at 6.50% by starting out with a fully-amortized payment at a lower rate and slowly increasing that rate each year until the final rate is achieved.

If the "rate stepping" all the way down to 3.00% isn't enough to hit a 38% DTI, then the whole thing is recalculated with a 40-year term, rather than with the remaining term of the loan. This part won't mean much if the loan was originally a 40-year term (and lots of OAs were) and it's only a year or two old. However, if the loan was originally a 30-year, extending the amortization term by another 10 years may reduce the payment enough to hit the 38% limit. The tricky part here for securitized loans, though, is that some and possibly most of these securities have a maximum loan maturity of 30 years written into the deal docs. So the modification will not actually extend the legal maturity date of the loan to 40 years; it will simply create a balloon loan (principal due in 30 years but payment calculated over 40 years).

If the term extension, added to the rate reduction, still doesn't hit the number, then and only then will the FDIC use "principal forbearance." The real issue I wanted to get to today was that part. What the FDIC apparently means by "principal forbearance" is not what most people think they mean by "principal reduction." The rate reduction on these loans, in contrast, is a true permanent reduction in the interest rate: the borrower is never in any scenario obligated to "make up" or pay back the difference between the original interest rate and the reduced rate.

However, with the principal, what the FDIC is doing is not forgiving principal but offering an interest-free forbearance of repayment of part of the principal. This means that the actual principal amount due and payable at maturity of the loan (or sale of the property) is the original unmodified principal amount, less any and all periodic principal payments the borrower makes until maturity or sale. However, the contractual payment the borrower makes is no longer "fully amortized," it is partially amortized, because a portion of the loan's principal is excluded from the amortization calculation, essentially making that portion a zero-interest balloon payment. (There may already be a balloon payment on this loan, if its original term was less than 40 years. But that balloon is not zero-interest. Confused yet?)

Here's an example: the remaining principal balance of the loan at modification is $100,000. We have already gotten down to a 3.00% first-step rate and a 40-year amortization, but the payment still results in an HTI greater than 38%. Therefore we take, say, 10% of the balance out of the amortization formula, meaning we calculate the payment on a $90,000 balance at 3.00% for 40 years. That would reduce the loan payment from $357.98 to $322.19. The remaining $10,000 in principal is still secured by the mortgage, so it would be due and payable in a lump sum (a "balloon payment") at the original maturity date of the loan. If the borrower sold the home or refinanced prior to maturity, the $10,000 is due and payable at the time, in addition to the remaining balance of the rest of the loan ($90,000 less amortized principal payments).

So "principal forbearance" does not mean principal "forgiveness." It certainly means that the effective interest rate on such loans is lower than the Freddie Mac survey rate, discounted for the stepping or not, because the contractual interest is not charged on the entire loan balance. It certainly means that the investor is going to have to write down the forborne principal when the modification is done, since this falls under the accounting rules that make you write down a loan to the amount considered collectible, and it is clear that a loan in this much trouble, with property values where they are, probably is not going to pay you back 100% of principal. But if, in fact, property values recover in the future and the home sells for at least the total loan amount due, the investor will receive that forborne principal back as a recovery.

This is not the same thing, technically, as a "shared appreciation" provision; it's rather more a compromise between shared appreciation and outright principal forgiveness. The borrower never has to pay the foregone interest on the forborne principal out of future sales proceeds or in any way "make the investor whole" for the rate reduction. But unlike outright forgiveness, the borrower does have to pay the full principal amount back out of sales (or refinance) proceeds.

Which, of course, leads us to wonder what happens if there's never enough sales proceeds to pull this off. My guess is that we're going through all this "principal forbearance" business, which isn't exactly easy for your average consumer to understand, because investors like it better than outright forgiveness and it's supposed to mitigate the "moral hazard" problem. But the other side is that the FDIC or whoever buys that portfolio of modified loans is going to face the possibility of being confronted with a cohort of loans needing short sales or short refis in a year or two, because some borrowers will always need to move on before home prices "recover."

At some level, it seems a bit odd to do this elaborate "forbearance" of principal in the original workout, only to have to cave in and do outright forgiveness of principal down the road in a second workout involving a short sale. The FDIC, I suspect, is making a rather different set of assumptions about how long-term the commitment to homeownership is likely to be in a portfolio like IndyMac's, and how long it will take for property values to recover, than I would. After all, this FDIC program is not--unlike, say, the new FHA short-refi program--reducing principal to achieve "above water" loans. It is forbearing principal only as a last resort, if the rate reduction and term extension doesn't work, and only enough to hit an "affordable" monthly payment. That means it is possible that loans could get a principal forbearance that still leaves them underwater; they just become "affordable" underwater loans. And that, unfortunately, is what puts you at risk of having to do a short sale down the road when the borrower needs to move or just can no longer handle having 38% of pre-tax income going to the house payment with all the other bills they have.

The JP Morgan analysts note that maximum principal forbearances on the IndyMac portfolio aren't likely to be that much: even a loan that originally had an HTI of 60% (which is extremely high even for stated income loans; remember that this isn't DTI or total debt-to-income ratio) and that got a 400 bps rate reduction plus a 10-year term extension would require only about a 17-18% principal forbearance to hit 38%. A loan that started out with a 45% HTI would be unlikely to need any principal forbearance at all, because the rate and term adjustments would be sufficient. The difficulty for analysts of the IndyMac-serviced loan pools, both securitized and unsecuritized, is that we don't really know what current (real) HTIs are. We have reported DTIs--total house payment plus all other monthly debt--but those were based on original reported income. We are pretty sure that actual current income for these borrowers is less than what was originally reported, but since databases stopped reporting HTI and DTI, relying solely on DTI alone, we don't know how many of these borrowers have high DTIs resulting from very high house payments and not much other debt, versus relatively reasonable house payments and a lot of other debt. The FDIC's approach will help the former but not the latter. While an 18% principal forbearance may sound like a lot, in terms of IndyMac's actual loan portfolio it may not work out to much if only a tiny sliver of loans have HTIs that high (and managed to make even the first payment). The real impact on investors will be the interest reductions and cash-flow changes resulting from slowing down the amortization to 40 years.

Bottom line: there just isn't a free lunch, not for anybody.

(Hat tip to Hoover for sending me the Morgan report. Hat tip to Morgan analysts for clarifying this subject. Note to Morgan analysts: the past tense of "forbear" is "forborne," not "forbeared." Y'all owe me a new keyboard.)

Personal Income and Outlays Report Suggests Slowdown

by Calculated Risk on 8/29/2008 09:16:00 AM

From the BEA: July Personal Income and Outlays

Real DPI decreased 1.7 percent in July, compared with a decrease of 2.6 percent in June. Real PCE decreased 0.4 percent, compared with a decrease of 0.1 percent.So real Disposable Personal Income (DPI) declined in both June and July, as did real Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE). This suggests that the impact from the stimulus checks is mostly behind us, and there is a good chance PCE growth will be negative in the 2nd half of 2008.

For more, see the WSJ: Consumer Spending Slowed in July As Inflation Continued to Take Toll

Thursday, August 28, 2008

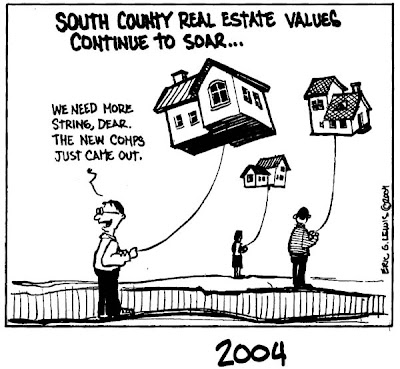

Cartoon of the Day

by Calculated Risk on 8/28/2008 09:00:00 PM

All: While I'm gone, Tanta and Paul Jackson (of Housing Wire) will be posting. Plus a guest post or two ... I've also scheduled some cartoon of the day posts. Enjoy.

To start, here is the first in a series on housing from Eric G. Lewis, a freelance cartoonist living in Orange County, CA. This is from 2003:

Click on cartoon for larger image in new window.

Bank of China Reduces Fannie, Freddie Investments

by Calculated Risk on 8/28/2008 07:40:00 PM

From the Financial Times: Bank of China flees Fannie-Freddie

Bank of China has cut its portfolio of securities issued or guaranteed by troubled US mortgage financiers Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac by a quarter since the end of June.This selling is probably why the spread between Fannie and Freddie debt yields and Treasury debt is so high. From the WSJ last week: Deflating Mortgage Rates

The sale by China’s fourth largest commercial bank, which reduced its holdings of so-called agency debt by $4.6bn is a sign of nervousness among foreign buyers of Fannie and Freddie’s bonds and guaranteed securities.

The differences, or spreads, between Fannie's and Freddie's debt yields and Treasury yields have widened considerably since the start of the housing crisis because of jitters about the highly leveraged companies' stability. Last September, Fannie issued three-year debt at 0.55% over Treasury yields. Last week, it paid 1.23% over Treasury yields.So there was probably more foreign selling in July and August.