by Calculated Risk on 4/04/2008 07:11:00 PM

Friday, April 04, 2008

Some Prescient Testimony from the S&L Crisis

Andrew Leonard at Salon provides some Congressional testimony after the S&L Crisis in "The next time we have Black Monday"

Prescient is too mild a word to describe [Stephen] Pizzo's testimony. I recommend reading it in its entirety, so as to savor the full flavor of his brimstone and fire. But here is a choice excerpt, featuring Pizzo's prediction as to the likely baleful consequences of allowing commercial banks to play with securities. ...As we autopsied dead savings and loans, we were absolutely amazed by the number of ways thrift rogues were able to circumvent, neuter, and defeat firewalls designed to safeguard the system against self-dealing and abuse. ...

... billions of federally insured dollars will disappear ...

That will happen, not might happen but will happen, and when it does these too-big-to-fail banks will have to be propped up with Federal money. In the smoking aftermath, Congress can stand around and wring its hands and give speeches about how awful it is that these bankers violated the spirit of the law, but once again, the money will be gone, the bill will have come due, and taxpayers will again be required to cough it up.

Fitch Downgrades MBIA

by Calculated Risk on 4/04/2008 05:19:00 PM

From Bloomberg: MBIA Loses AAA Insurer Rating From Fitch Over Capital

Fitch Ratings cut the rating on MBIA Inc.'s insurance unit to AA from AAA, saying the bond insurer no longer has enough capital to warrant the top ranking.

...

Fitch issued the new, lower rating even though Armonk, New York-based MBIA asked the ratings company last month to stop assessing its credit worthiness.

Denver House Prices

by Calculated Risk on 4/04/2008 02:57:00 PM

Luke Mullins at U.S. News and World Report writes: Some Home Prices Are Actually Rising in Denver. This is an excerpt from an interview with Ryan Tomazin, the director and chief financial officer of Integrated Asset Services.

Mullins: Let's look at a specific area. What's happening in Denver, where prices overall have dropped more than 5 percent in the past year?This story reminds us that all areas aren't the same; price action can be different neighborhood by neighborhood.

Tomazin: As a whole, it's down. We're seeing historic all-time highs for foreclosures, all those types of things that are currently the storylines. But within the city, there are areas that are very hard hit in Denver, and yet there are areas that have been relatively unaffected or even appreciating.

[see interesting neighborhood by neighborhood map in article]

Q: The map reflects the price change for detached, single-family homes over the past year, according to Integrated Asset Services. Why are the property values of some neighborhoods [those in green or blue] rising?

Tomazin: In Denver specifically, what we're seeing is there are some neighborhoods that are very valuable—old historic neighborhoods. Their values have historically held up just because there is a limited supply. They are located very centrally, and they are in fairly affluent areas.

Q: What about the neighborhoods in red?

Tomazin: Denver had some of the most unregulated lending practices in the country. And many of the borrowers in these areas are not able to meet the new payments of the adjustable-rate mortgages.

And Denver did not see much house appreciation compared to many other cities, so prices will probably not fall as far either.

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.This graph show the real (inflation adjusted) Case-Shiller house price indices for Denver and Los Angeles. Real prices have been flat in Denver for about six years - before turning down recently - so prices are probably much closer to the bottom in Denver than in Los Angeles.

Still Tomazin might be a little optimistic that prices are near the bottom in Denver - mostly because there is too much inventory right now - and my guess is there will be further price declines.

San Diego Office vacancy rate 'skyrockets'

by Calculated Risk on 4/04/2008 01:32:00 PM

From Mike Freeman at the San Diego Union-Tribune: Local office vacancy rate skyrockets

San Diego's office vacancy rate spiked to its highest level since 1996 in the first quarter thanks to a combination of weak demand and new buildings coming to market.For residential real estate, San Diego was one of the first cities impacted by the housing bust (declining transactions, falling prices). So it's not surprising that San Diego would also be one the first cities with falling demand for office space - while the supply is still rising due to the commercial real estate construction boom of recent years.

Direct vacancy – landlord-controlled office space that's empty – was 15.1 percent countywide, according to a CB Richard Ellis report issued yesterday. That's up from 11.5 percent a year earlier.

...

Net absorption – a real estate term that measures the amount of space leased versus the amount vacated – was negative 190,000 square feet for the quarter.

...

The slumping demand comes after a wave of office construction over the past couple of years.

The combination of falling demand for office space, and increasing supply, will probably be repeated in many cities across the country.

Housing Bust Duration

by Calculated Risk on 4/04/2008 11:59:00 AM

This first graph shows real Case-Shiller house prices for Los Angeles and the Composite 20 Index (20 large cities). The indices are adjusted with CPI less Shelter. Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

The most obvious feature is the size of the current housing price bubble compared to the late '80s housing bubble in Los Angeles.

The Composite 20 bubble looks similar (although larger) to the previous Los Angeles bubble. (Note the Composite 20 index started in 2000).

Perhaps we can overlay the current Composite 20 bubble on top of the previous Los Angeles bubble and learn something about the possible duration of the current bust.

In the second graph, the real price peaks are lined up for late '80s bubble in Los Angeles, and the current Composite 20 bubble. Note that the real price peak for the Composite 20 was flat for several months, so the real peak was chosen as May '06. It could also be a few months later. The peak and trough for the Los Angeles bubble are marked on the graph.

The peak and trough for the Los Angeles bubble are marked on the graph.

Prices are falling faster this time, probably because the bubble was larger.

It might be reasonable to expect that the dynamics of the current bust will be similar to the previous bust. After another year (or two) of rapidly falling prices, it's very likely that real prices will continue to fall - but at a slower pace. During the last few years of the bust, real prices will be flat or decline slowly - and the conventional wisdom will be that homes are a poor investment.

The Los Angeles bust took 86 months in real terms from peak to trough (about 7 years) using the Case-Shiller index. If the Composite 20 bust takes a similar amount of time, the real price bottom will happen in early 2013 or so. (But prices would be close in 2010).

Jobs: Nonfarm Payrolls Decline 80,000 in March

by Calculated Risk on 4/04/2008 08:40:00 AM

From the BLS: Employment Situation Summary

The unemployment rate rose from 4.8 to 5.1 percent in March, and nonfarm payroll employment continued to trend down (-80,000), the Bureau of Labor Statistics of the U.S. Department of Labor reported today. Over the past 3 months, payroll employment has declined by 232,000.

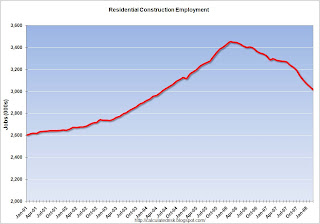

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.Note: graph doesn't start at zero to better show the change.

Residential construction employment declined 31,000 in March, and including downward revisions to previous months, is down 442.9 thousand, or about 12.8%, from the peak in February 2006. (compared to housing starts off over 50%).

The second graph shows the unemployment rate and the year-over-year change in employment vs. recessions.

Unemployment was higher, and the rise in unemployment, from a cycle low of 4.4% to 5.1% is a recession warning.

Also concerning is the YoY change in employment is barely positive (the economy has added just over 500 thousand jobs in the last year), also suggesting a recession.

The WSJ reports: Economy Shed Jobs in March, Fueling Fears of Recession

Nonfarm payrolls fell 80,000 in March, the Labor Department said Friday, its biggest decline in five years, after falling by 76,000 in both January and February. Both were revised to show even bigger losses.Overall this is a very weak report.

Had it not been for a rise in government jobs last month, payrolls would have fallen by around 100,000.

Thursday, April 03, 2008

Fed's Yellen: House Prices "still too high"

by Calculated Risk on 4/03/2008 09:52:00 PM

San Francisco Fed President Janet Yellen spoke today: The Financial Markets, Housing, and the Economy. Yellen points out that delinquency are more closely correlated to falling house prices as opposed to interest rate resets:

Much has been made in the news about the role of interest rate resets in causing delinquencies and foreclosures. After all, delinquency rates on variable-rate subprime loans are far higher and are rising much faster than those on fixed-rate subprime mortgages. However, research suggests that this has not been a major factor, at least so far. The vast majority of subprime loans are recent vintages, so only a fraction had hit reset dates as of late 2007. Moreover, in many cases, the initial—or “teaser”—rates were not set that far below the formula, and some of the short-term rates that enter into these formulas have come down since last summer. Moreover, it turns out that variable-rate subprime loans are more likely to become delinquent because the pool of borrowers that took out these loans had higher risk characteristics than those who took out fixed rate loans.Perhaps we could state this simply: "It's the house prices, stupid!"

To the extent that the subprime meltdown is tied to declining house prices rather than interest rate resets, other borrowers, including prime borrowers, also could be affected. Indeed, while default rates for the latter loans are lower than for subprime loans, delinquency rates among all categories are highly correlated with house price declines across regions of the country. More formal statistical analysis confirms that differences in house-price change account for most of the regional differences in delinquency rates, whether borrowers are prime or nonprime, or whether loans have fixed or variable rates.

This analysis underscores the importance of house-price movements both to future developments in the housing sector and also to the ultimate magnitude of credit losses that are likely to be realized by leveraged financial institutions on their holdings of mortgage-backed securities and other housing-related loans. Looking ahead, it seems likely that the period of house price declines will not be over very soon, since some models of the fundamental value of houses suggest that prices are still too high, and futures markets for house prices indicate further declines this year. This trajectory of house prices plays a critical role in the economic outlook ...

all emphasis added

And a few excerpts on the economic outlook:

It seems likely that residential construction will be a major drag on the overall economy through the end of this year and into 2009.Containment is lost. Recession!

Until recently, the deflating housing bubble had not spilled over to the rest of the economy. But now it has. Based on monthly data that cover most of the first quarter, it appears that growth in consumption and business investment spending has slowed markedly after years of robust performance, and, as a result, the economy has all but stalled and could contract over the first half of the year.

Note: Yellen is not a voting member of the FOMC this year.

IMF: Central Banks Should "Lean against the Wind" of Asset Prices

by Calculated Risk on 4/03/2008 05:21:00 PM

The IMF has a new report out on housing: The Changing Housing Cycle and the Implications for Monetary Policy (hat tip Glenn)

Note: the IMF chart on page 13 is incorrect. This is the same error Bear Stearns made last year: see Bear Stearns and RI as Percent of GDP. It doesn't make sense to divide real quantities, since the price indexes are different. Dividing by nominal quantities gives the correct result. This Fed paper explains the error in using real ratios from chained series, and recommends the approach I used. See: A Guide to the Use of Chain Aggregated NIPA Data, Section 4.

The IMF piece analyzes the connection between housing and the business cycle (housing has typically led the business cycle both into and out of recessions). They also discuss the spillover effects of a housing boom on consumer spending, and finally the IMF argues the Central Banks should 'lean against the wind' of rapidly rising asset prices.

The main conclusion of this analysis is that changes in housing finance systems have affected the role played by the housing sector in the business cycle in two different ways. First, the increased use of homes as collateral has amplified the impact of housing sector activity on the rest of the economy by strengthening the positive effect of rising house prices on consumption via increased household borrowing—the “financial accelerator” effect. Second, monetary policy is now transmitted more through the price of homes than through residential investment.We've discussed this many times: increasing asset prices (and mortgage equity withdrawal) probably increased consumer spending significantly as asset prices increased, and declining assets prices will likely now be a drag on consumer spending.

In particular, the evidence suggests that more flexible and competitive mortgage markets have amplified the impact of monetary policy on house prices and thus, ultimately, on consumer spending and output. Furthermore, easy monetary policy seems to have contributed to the recent run-up in house prices and residential investment in the United States, although its effect was probably magnified by the loosening of lending standards and by excessive risk-taking by lenders.

And on Central Bank policy:

[C]entral banks should be ready to respond to abnormally rapid increases in asset prices by tightening monetary policy even if these increases do not seem likely to affect inflation and output over the short term. ... asset price misalignments matter because of the risks they pose for financial stability and the threat of a severe output contraction should a bubble burst, which would also lower inflation pressure.

Wharton on the Future of Securitization

by Anonymous on 4/03/2008 04:04:00 PM

Sigh.

Some days all I can do is sigh.

The Wharton faculty interviewed for this piece, "Coming Soon ... Securitization with a New, Improved (and Perhaps Safer) Face," seem mostly to believe that securitization of mortgage loans isn't going to to away after the recent debacle, nor is it going to go unchanged. I certainly agree with both claims. But I hate stuff like this. Those of you who think my posts on the subject are much too long and tediously detailed might like it a lot. Certainly you can read it and make up your own mind.

This is where I started heaving the great sighs:

Allen believes financial markets will get back into the business of securitizing mortgage debt, but only after making some major changes. One new feature of future securitization deals, he says, could be a requirement that loan originators hold at least part of the loans they write on their books. Before the current crisis, loans were bundled into complex tranches that were passed through the financial system and onto buyers with little ability to assess the real value of the individual assets.This is the logic of the text (if not, perhaps, Professor Allan's logic):

"The way the collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) and other vehicles are structured will change. They are too complicated," says Allen. "I'm sure the industry will figure out how to do it. There will be a lot of industry-generated reform and the industry will prosper. This is not, in my view, something that should be regulated."

1. Originators will be required to retain some credit exposure, [because?]

2. Investors have insufficient information to assess loan level risk, [because]

3. Securitization structures are too complex.

4. Therefore the industry will change these things and no regulation is needed.

Forget item four; that follows from any set of premises for some people. I just want to know how having originators (I do not think this means "security issuers" like investment banks) retain some exposure to the underlying credits will solve either the investor due-diligence problems or the complexity problems. I do not know why failing to distinguish between mortgage-backed securities and such vehicles as CDOs is being helpful in this context. I don't know why having simpler MBS structures will necessarily make investor due diligence any better: am I the only one who imagines that investor due diligence could be minimal on a plain old single-class pass-through if you waved a distracting enough coupon in front of them?

Well, the next expert brings that up:

According to Wharton finance professor Richard J. Herring, for decades, mortgage securitization was backed by government guarantees through Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and it worked well. Of course, these agencies were regulated and bound by less-risky underwriting standards than those that ultimately prevailed in the subprime market which was also, potentially, more profitable. Indeed, default rates were so low in the mortgage-based securities market that banks and other private financial institutions were eager to take a piece of the residential business.Those GSE securities that worked so well for so long were quite simple in structure, and I'm still willing to bet that a lot of people invested in them without knowing much at all about the credit risk of the underlying loans. They relied on the guarantee, on the liquidity of the GSE MBS market, and on the "homogeneity" of the mortgage world back then.

And, you know, they didn't earn much. Conservative credit risk is not the sort of thing that generates princely yields. It was not, in fact, just that margins on originating subprime loans were fatter. (Even at the height of the subprime boom, subprime was never more than 20% of originations, as far as I know. Low volume and high margin.) It was that prime quality mortgage-backed securities don't have high yields, and they can't. In a "normal" market, they aren't risky enough to have juicy yield. And furthermore, everyone (more or less) has one. Including investors in MBS. There's a limit to how willing we all are to put high-yielding MBS in our retirement accounts if it means we can't afford our mortgage payments. We have met the source of the underlying cash-flow, and it is us.

The lurking concept here is "leverage." You want to make the big bucks investing in MBS? You leverage them. That's where those CDOs came from. A whole lot of this complexity is driven by the "need" to goose the yield, not by some essential opacity of the underlying credits or the failure of originators to retain residuals--which, in fact, they actually did quite a bit of in there. The complexity came in because you can't get a tranche paying 12% out of a bunch of loans that pay 8% unless you create complex cash-flow structures hedged by complex rate swaps leading to re-securitization of tranches in new vehicles (parts of the MBS become CDOs, for instance).

So are all the rest of you convinced that market participants are going to give up on the chase for mo' better yield without regulation?

Leverage does get a mention later on:

Wharton real estate professor Joseph Gyourko notes that significant differences exist in the performance of commercial and residential real estate securities. "Securitized commercial property debt will come back once the market calms down," he says, adding that there has been very little default in commercial real estate finance. "You'll be able to pool mortgages and securitize them, but almost certainly won't be able to leverage them as much as you did in the past."Worry about commercial RE is just a side-effect of market tizzies? It's only individual homeowners who need to just get used to being left out of the party if they don't have the down payment? I begin to stop sighing and start to mutter . . .

The residential side, where there is significant default, is more problematic. Gyourko believes the residential market will go back to what it was in the mid-1990s and most borrowers will have to put

down at least 10% of the sales price. "We will get rid of the exotic, highly leveraged loans," he says. "That will lead to lower homeownership, but it should. We put a lot of people into homeownership that we shouldn't have."

Ah, but one distinguished professor has his eye on another party who could share some of the pain with the homeowner:

Wharton real estate professor Peter Linneman offers an intriguing prescription to bring prices down to the point where the industry can start to rebuild. He suggests that the government tell banks that if they want to maintain their federal insurance, they should fire their CEO by the end of the day, and the government will pay the CEO $10 million in severance. Ousting the former CEOs gives the new bank CEOs an incentive to write down all the bad assets immediately, so that any improvement will make them look good going forward. That would speed the painful process of gradual price declines.Yeah, I'm only half-throwing up. If these CEOs are indeed "responsible" for 80% of the worst credit crisis we've seen in most people's lifetimes, and they've been doing quite well out of it, why do we need to pay them another $10 million to go away? Because it's "innovative"? Because the First Deputy Assistant CEO waiting in the wings has a whole nuther plan we haven't heard yet for some reason, but they will pipe up with it as soon as the Guilty 1000 are gone? And it's going to be about how to wean themselves off the leveraged carry-trade in nine months? Maybe that plan would be worth $10 million, but do we get the money back if we aren't satisfied?

"There's plenty of money out there waiting for these assets to be written down to bargain prices," says Linneman. In another quarter or two, the lenders would have new cash and be ready to lend again. Meanwhile, he says, the government should tell bankers it will keep interest rates down but raise them after the end of the year. "That says, 'Get your house in order in the next nine months because the subsidy ends at the end of the year.'" Linneman figures that 1,000 CEOs are accountable for about 80% of the current lending mess. If the government were to spend $10 billion to restore liquidity to the market in nine months with only 1,000 people losing their jobs, it would be the best investment it could make to restore the economy. "I'm only half-kidding," he quips.

I am trying to avoid suggesting that maybe we'd get better CEOs out of better business schools. I'm not trying that hard, but I'm trying. As is quite often the case, I never know if some of these things sound so half-baked because of the writing--the urge to simplify complex ideas into palatable chunks--or because of the paucity of the underlying material. But I'm happy to blame a lot of the bad writing I see on what they teach in business schools.

There is some sense in here--but you'll have to go dig it out yourself. I've sighed so much I need a good drink. I certainly agree that the CDO is dead. So, probably, is the SIV. I'm still wondering about the multi-class structured MBS, but that doesn't seem to be the article's particular interest.

(Hat tip Bill & Bill)

Testimony on Bear Stearns

by Calculated Risk on 4/03/2008 01:26:00 PM

'Capital is not synonymous with liquidity.'From MarketWatch: Bear Stearns crisis tests liquidity rules, Cox says

Christopher Cox, SEC

[Cox] said that Bear Stearns was adequately capitalized "at all times" during March 10 to 17, "up to and including the time of its agreement to be acquired by J.P. Morgan Chase.From the WSJ: Regulators Defend Bear Rescue

But, facing skeptical lawmakers, Cox acknowledged that the firm had massive liquidity problems and that "capital is not synonymous with liquidity." He said the SEC is working with the five biggest Wall Street firms to make sure they increase their liquidity pools and redouble their focus on risk practices.

...

In one day -- March 13 -- Cox indicated, liquidity at Bear Stearns fell from $12.4 billion to $2 billion because of "the complete evaporation of confidence" in the company.

"I think the speed with which this happened is truly the distinguishing feature," the SEC chairman commented. "The Bear Stearns experience has challenged the measurement of liquidity in every regulatory approach, not only here in the United States but around the world."

"We judged that a sudden, disorderly failure of Bear would have brought with it unpredictable but severe consequences for the functioning of the broader financial system and the broader economy, with lower equity prices, further downward pressure on home values, and less access to credit for companies and households," Federal Reserve Bank of New York President Timothy Geithner said in testimony to the Senate Banking Committee.And also from MarketWatch, here is Geithner's presentation: N.Y. Fed's Geithner explains Bear Stearns deal

...

"If you want to say we bailed out markets in general, I guess that's true," Mr. Bernanke told the Senate Banking Committee, adding the Fed's role in the rescue was necessary given the fragile state of financial markets. "Under more normal conditions we might have come to a different decision" with respect to Bear Stearns, Mr. Bernanke said.

Geithner was the key player in this deal.