by Calculated Risk on 4/04/2008 08:40:00 AM

Friday, April 04, 2008

Jobs: Nonfarm Payrolls Decline 80,000 in March

From the BLS: Employment Situation Summary

The unemployment rate rose from 4.8 to 5.1 percent in March, and nonfarm payroll employment continued to trend down (-80,000), the Bureau of Labor Statistics of the U.S. Department of Labor reported today. Over the past 3 months, payroll employment has declined by 232,000.

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.Note: graph doesn't start at zero to better show the change.

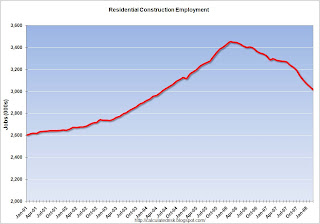

Residential construction employment declined 31,000 in March, and including downward revisions to previous months, is down 442.9 thousand, or about 12.8%, from the peak in February 2006. (compared to housing starts off over 50%).

The second graph shows the unemployment rate and the year-over-year change in employment vs. recessions.

Unemployment was higher, and the rise in unemployment, from a cycle low of 4.4% to 5.1% is a recession warning.

Also concerning is the YoY change in employment is barely positive (the economy has added just over 500 thousand jobs in the last year), also suggesting a recession.

The WSJ reports: Economy Shed Jobs in March, Fueling Fears of Recession

Nonfarm payrolls fell 80,000 in March, the Labor Department said Friday, its biggest decline in five years, after falling by 76,000 in both January and February. Both were revised to show even bigger losses.Overall this is a very weak report.

Had it not been for a rise in government jobs last month, payrolls would have fallen by around 100,000.

Thursday, April 03, 2008

Fed's Yellen: House Prices "still too high"

by Calculated Risk on 4/03/2008 09:52:00 PM

San Francisco Fed President Janet Yellen spoke today: The Financial Markets, Housing, and the Economy. Yellen points out that delinquency are more closely correlated to falling house prices as opposed to interest rate resets:

Much has been made in the news about the role of interest rate resets in causing delinquencies and foreclosures. After all, delinquency rates on variable-rate subprime loans are far higher and are rising much faster than those on fixed-rate subprime mortgages. However, research suggests that this has not been a major factor, at least so far. The vast majority of subprime loans are recent vintages, so only a fraction had hit reset dates as of late 2007. Moreover, in many cases, the initial—or “teaser”—rates were not set that far below the formula, and some of the short-term rates that enter into these formulas have come down since last summer. Moreover, it turns out that variable-rate subprime loans are more likely to become delinquent because the pool of borrowers that took out these loans had higher risk characteristics than those who took out fixed rate loans.Perhaps we could state this simply: "It's the house prices, stupid!"

To the extent that the subprime meltdown is tied to declining house prices rather than interest rate resets, other borrowers, including prime borrowers, also could be affected. Indeed, while default rates for the latter loans are lower than for subprime loans, delinquency rates among all categories are highly correlated with house price declines across regions of the country. More formal statistical analysis confirms that differences in house-price change account for most of the regional differences in delinquency rates, whether borrowers are prime or nonprime, or whether loans have fixed or variable rates.

This analysis underscores the importance of house-price movements both to future developments in the housing sector and also to the ultimate magnitude of credit losses that are likely to be realized by leveraged financial institutions on their holdings of mortgage-backed securities and other housing-related loans. Looking ahead, it seems likely that the period of house price declines will not be over very soon, since some models of the fundamental value of houses suggest that prices are still too high, and futures markets for house prices indicate further declines this year. This trajectory of house prices plays a critical role in the economic outlook ...

all emphasis added

And a few excerpts on the economic outlook:

It seems likely that residential construction will be a major drag on the overall economy through the end of this year and into 2009.Containment is lost. Recession!

Until recently, the deflating housing bubble had not spilled over to the rest of the economy. But now it has. Based on monthly data that cover most of the first quarter, it appears that growth in consumption and business investment spending has slowed markedly after years of robust performance, and, as a result, the economy has all but stalled and could contract over the first half of the year.

Note: Yellen is not a voting member of the FOMC this year.

IMF: Central Banks Should "Lean against the Wind" of Asset Prices

by Calculated Risk on 4/03/2008 05:21:00 PM

The IMF has a new report out on housing: The Changing Housing Cycle and the Implications for Monetary Policy (hat tip Glenn)

Note: the IMF chart on page 13 is incorrect. This is the same error Bear Stearns made last year: see Bear Stearns and RI as Percent of GDP. It doesn't make sense to divide real quantities, since the price indexes are different. Dividing by nominal quantities gives the correct result. This Fed paper explains the error in using real ratios from chained series, and recommends the approach I used. See: A Guide to the Use of Chain Aggregated NIPA Data, Section 4.

The IMF piece analyzes the connection between housing and the business cycle (housing has typically led the business cycle both into and out of recessions). They also discuss the spillover effects of a housing boom on consumer spending, and finally the IMF argues the Central Banks should 'lean against the wind' of rapidly rising asset prices.

The main conclusion of this analysis is that changes in housing finance systems have affected the role played by the housing sector in the business cycle in two different ways. First, the increased use of homes as collateral has amplified the impact of housing sector activity on the rest of the economy by strengthening the positive effect of rising house prices on consumption via increased household borrowing—the “financial accelerator” effect. Second, monetary policy is now transmitted more through the price of homes than through residential investment.We've discussed this many times: increasing asset prices (and mortgage equity withdrawal) probably increased consumer spending significantly as asset prices increased, and declining assets prices will likely now be a drag on consumer spending.

In particular, the evidence suggests that more flexible and competitive mortgage markets have amplified the impact of monetary policy on house prices and thus, ultimately, on consumer spending and output. Furthermore, easy monetary policy seems to have contributed to the recent run-up in house prices and residential investment in the United States, although its effect was probably magnified by the loosening of lending standards and by excessive risk-taking by lenders.

And on Central Bank policy:

[C]entral banks should be ready to respond to abnormally rapid increases in asset prices by tightening monetary policy even if these increases do not seem likely to affect inflation and output over the short term. ... asset price misalignments matter because of the risks they pose for financial stability and the threat of a severe output contraction should a bubble burst, which would also lower inflation pressure.

Wharton on the Future of Securitization

by Anonymous on 4/03/2008 04:04:00 PM

Sigh.

Some days all I can do is sigh.

The Wharton faculty interviewed for this piece, "Coming Soon ... Securitization with a New, Improved (and Perhaps Safer) Face," seem mostly to believe that securitization of mortgage loans isn't going to to away after the recent debacle, nor is it going to go unchanged. I certainly agree with both claims. But I hate stuff like this. Those of you who think my posts on the subject are much too long and tediously detailed might like it a lot. Certainly you can read it and make up your own mind.

This is where I started heaving the great sighs:

Allen believes financial markets will get back into the business of securitizing mortgage debt, but only after making some major changes. One new feature of future securitization deals, he says, could be a requirement that loan originators hold at least part of the loans they write on their books. Before the current crisis, loans were bundled into complex tranches that were passed through the financial system and onto buyers with little ability to assess the real value of the individual assets.This is the logic of the text (if not, perhaps, Professor Allan's logic):

"The way the collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) and other vehicles are structured will change. They are too complicated," says Allen. "I'm sure the industry will figure out how to do it. There will be a lot of industry-generated reform and the industry will prosper. This is not, in my view, something that should be regulated."

1. Originators will be required to retain some credit exposure, [because?]

2. Investors have insufficient information to assess loan level risk, [because]

3. Securitization structures are too complex.

4. Therefore the industry will change these things and no regulation is needed.

Forget item four; that follows from any set of premises for some people. I just want to know how having originators (I do not think this means "security issuers" like investment banks) retain some exposure to the underlying credits will solve either the investor due-diligence problems or the complexity problems. I do not know why failing to distinguish between mortgage-backed securities and such vehicles as CDOs is being helpful in this context. I don't know why having simpler MBS structures will necessarily make investor due diligence any better: am I the only one who imagines that investor due diligence could be minimal on a plain old single-class pass-through if you waved a distracting enough coupon in front of them?

Well, the next expert brings that up:

According to Wharton finance professor Richard J. Herring, for decades, mortgage securitization was backed by government guarantees through Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, and it worked well. Of course, these agencies were regulated and bound by less-risky underwriting standards than those that ultimately prevailed in the subprime market which was also, potentially, more profitable. Indeed, default rates were so low in the mortgage-based securities market that banks and other private financial institutions were eager to take a piece of the residential business.Those GSE securities that worked so well for so long were quite simple in structure, and I'm still willing to bet that a lot of people invested in them without knowing much at all about the credit risk of the underlying loans. They relied on the guarantee, on the liquidity of the GSE MBS market, and on the "homogeneity" of the mortgage world back then.

And, you know, they didn't earn much. Conservative credit risk is not the sort of thing that generates princely yields. It was not, in fact, just that margins on originating subprime loans were fatter. (Even at the height of the subprime boom, subprime was never more than 20% of originations, as far as I know. Low volume and high margin.) It was that prime quality mortgage-backed securities don't have high yields, and they can't. In a "normal" market, they aren't risky enough to have juicy yield. And furthermore, everyone (more or less) has one. Including investors in MBS. There's a limit to how willing we all are to put high-yielding MBS in our retirement accounts if it means we can't afford our mortgage payments. We have met the source of the underlying cash-flow, and it is us.

The lurking concept here is "leverage." You want to make the big bucks investing in MBS? You leverage them. That's where those CDOs came from. A whole lot of this complexity is driven by the "need" to goose the yield, not by some essential opacity of the underlying credits or the failure of originators to retain residuals--which, in fact, they actually did quite a bit of in there. The complexity came in because you can't get a tranche paying 12% out of a bunch of loans that pay 8% unless you create complex cash-flow structures hedged by complex rate swaps leading to re-securitization of tranches in new vehicles (parts of the MBS become CDOs, for instance).

So are all the rest of you convinced that market participants are going to give up on the chase for mo' better yield without regulation?

Leverage does get a mention later on:

Wharton real estate professor Joseph Gyourko notes that significant differences exist in the performance of commercial and residential real estate securities. "Securitized commercial property debt will come back once the market calms down," he says, adding that there has been very little default in commercial real estate finance. "You'll be able to pool mortgages and securitize them, but almost certainly won't be able to leverage them as much as you did in the past."Worry about commercial RE is just a side-effect of market tizzies? It's only individual homeowners who need to just get used to being left out of the party if they don't have the down payment? I begin to stop sighing and start to mutter . . .

The residential side, where there is significant default, is more problematic. Gyourko believes the residential market will go back to what it was in the mid-1990s and most borrowers will have to put

down at least 10% of the sales price. "We will get rid of the exotic, highly leveraged loans," he says. "That will lead to lower homeownership, but it should. We put a lot of people into homeownership that we shouldn't have."

Ah, but one distinguished professor has his eye on another party who could share some of the pain with the homeowner:

Wharton real estate professor Peter Linneman offers an intriguing prescription to bring prices down to the point where the industry can start to rebuild. He suggests that the government tell banks that if they want to maintain their federal insurance, they should fire their CEO by the end of the day, and the government will pay the CEO $10 million in severance. Ousting the former CEOs gives the new bank CEOs an incentive to write down all the bad assets immediately, so that any improvement will make them look good going forward. That would speed the painful process of gradual price declines.Yeah, I'm only half-throwing up. If these CEOs are indeed "responsible" for 80% of the worst credit crisis we've seen in most people's lifetimes, and they've been doing quite well out of it, why do we need to pay them another $10 million to go away? Because it's "innovative"? Because the First Deputy Assistant CEO waiting in the wings has a whole nuther plan we haven't heard yet for some reason, but they will pipe up with it as soon as the Guilty 1000 are gone? And it's going to be about how to wean themselves off the leveraged carry-trade in nine months? Maybe that plan would be worth $10 million, but do we get the money back if we aren't satisfied?

"There's plenty of money out there waiting for these assets to be written down to bargain prices," says Linneman. In another quarter or two, the lenders would have new cash and be ready to lend again. Meanwhile, he says, the government should tell bankers it will keep interest rates down but raise them after the end of the year. "That says, 'Get your house in order in the next nine months because the subsidy ends at the end of the year.'" Linneman figures that 1,000 CEOs are accountable for about 80% of the current lending mess. If the government were to spend $10 billion to restore liquidity to the market in nine months with only 1,000 people losing their jobs, it would be the best investment it could make to restore the economy. "I'm only half-kidding," he quips.

I am trying to avoid suggesting that maybe we'd get better CEOs out of better business schools. I'm not trying that hard, but I'm trying. As is quite often the case, I never know if some of these things sound so half-baked because of the writing--the urge to simplify complex ideas into palatable chunks--or because of the paucity of the underlying material. But I'm happy to blame a lot of the bad writing I see on what they teach in business schools.

There is some sense in here--but you'll have to go dig it out yourself. I've sighed so much I need a good drink. I certainly agree that the CDO is dead. So, probably, is the SIV. I'm still wondering about the multi-class structured MBS, but that doesn't seem to be the article's particular interest.

(Hat tip Bill & Bill)

Testimony on Bear Stearns

by Calculated Risk on 4/03/2008 01:26:00 PM

'Capital is not synonymous with liquidity.'From MarketWatch: Bear Stearns crisis tests liquidity rules, Cox says

Christopher Cox, SEC

[Cox] said that Bear Stearns was adequately capitalized "at all times" during March 10 to 17, "up to and including the time of its agreement to be acquired by J.P. Morgan Chase.From the WSJ: Regulators Defend Bear Rescue

But, facing skeptical lawmakers, Cox acknowledged that the firm had massive liquidity problems and that "capital is not synonymous with liquidity." He said the SEC is working with the five biggest Wall Street firms to make sure they increase their liquidity pools and redouble their focus on risk practices.

...

In one day -- March 13 -- Cox indicated, liquidity at Bear Stearns fell from $12.4 billion to $2 billion because of "the complete evaporation of confidence" in the company.

"I think the speed with which this happened is truly the distinguishing feature," the SEC chairman commented. "The Bear Stearns experience has challenged the measurement of liquidity in every regulatory approach, not only here in the United States but around the world."

"We judged that a sudden, disorderly failure of Bear would have brought with it unpredictable but severe consequences for the functioning of the broader financial system and the broader economy, with lower equity prices, further downward pressure on home values, and less access to credit for companies and households," Federal Reserve Bank of New York President Timothy Geithner said in testimony to the Senate Banking Committee.And also from MarketWatch, here is Geithner's presentation: N.Y. Fed's Geithner explains Bear Stearns deal

...

"If you want to say we bailed out markets in general, I guess that's true," Mr. Bernanke told the Senate Banking Committee, adding the Fed's role in the rescue was necessary given the fragile state of financial markets. "Under more normal conditions we might have come to a different decision" with respect to Bear Stearns, Mr. Bernanke said.

Geithner was the key player in this deal.

Overdue Consumer Debts Highest Since 1992

by Calculated Risk on 4/03/2008 10:46:00 AM

"The rise in consumer credit delinquencies is consistent with a rapidly slowing economy. Stress in the housing market still dominates the story, but it's a broader tale."From Bloomberg: Overdue Consumer Debts Highest Since 1992, ABA Says

American Bankers Association chief economist James Chessen, April 3, 2008

Consumers fell behind on car, credit-card and home-equity loans at the highest level in 15 years during the fourth quarter, another sign the U.S. economy is slowing, according to an American Bankers Association survey.This is the highest level of consumer debt delinquencies since just after the last consumer led recession. And this data was for Q4 2007. If Chessen thought the economy was "rapidly slowing" in Q4, wait until the data is available for Q1 2008!

Fed Provides More Details on Bear Stearns Portfolio

by Calculated Risk on 4/03/2008 10:38:00 AM

From the NY Fed: Portfolio Overview

Following is an overview of the portfolio supporting the loan to be extended by the Federal Reserve in connection with the proposed acquisition of Bear Stearns by JPMorgan Chase.

The $29 billion credit extension is supported by assets that were valued at $30 billion by Bear Stearns, which valued the assets at market value on March 14. JPMorgan Chase will extend a subordinated loan for $1 billion that will absorb losses, if any, on the sale of these assets before the Federal Reserve.

The portfolio supporting the credit extensions consists largely of mortgage related assets. In particular, it includes cash assets as well as related hedges.

The cash assets consist of investment grade securities (i.e. securities rated BBB- or higher by at least one of the three principal credit rating agencies and no lower than that by the others) and residential or commercial mortgage loans classified as “performing”. All of the assets are current as to principal and interest (as of March 14, 2008). All securities are domiciled and issued in the U.S. and denominated in U.S. dollars.

The portfolio consists of collateralized mortgage obligations (CMOs), the majority of which are obligations of government-sponsored entities (GSEs), such as the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation (“Freddie Mac”), as well as asset-backed securities, adjustable-rate mortgages, commercial mortgage-backed securities, non-GSE CMOs, collateralized bond obligations, and various other loan obligations.

The assets were reviewed by the Federal Reserve and its advisor, BlackRock Financial Management. The assets were not individually selected by JPMorgan Chase or Bear Stearns.

The Federal Reserve would be required by GAAP to report the valuation of the portfolio on an annual basis. We will report the valuation and recoveries from liquidation of the portfolio on a quarterly basis, subject to annual review by our outside auditors Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu.

The Federal Reserve will make arrangements with the appropriate Committee staffs to allow review of the list of assets on a confidential basis that permits appropriate Congressional oversight of the Federal Reserve's actions while also protecting the ability of the Federal Reserve to minimize risk of loss and danger to markets and preserve privacy and other confidentiality concerns.

Weekly Unemployment Claims Indicate Probable Recession

by Calculated Risk on 4/03/2008 10:21:00 AM

The 4-week moving average of weekly unemployment insurance claims reached 374,500 this week.

From the Department of Labor:

In the week ending March 29, the advance figure for seasonally adjusted initial claims was 407,000, an increase of 38,000 from the previous week's revised figure of 369,000. The 4-week moving average was 374,500, an increase of 15,750 from the previous week's revised average of 358,750.

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.This graph shows the weekly claims and the four week moving average of weekly unemployment claims since 1989. The four week moving average has been trending upwards for the last few months, and the level is now solidly above the possible recession level (approximately 350K).

Labor related gauges are at best coincident indicators, and this indicator suggests the economy is in recession. Notice that following the previous two recessions, weekly unemployment claims stayed elevated for a couple of years after the official recession ended - suggesting the weakness in the labor market lingered. The same will probably be true for the current recession (probable).

Note: There is nothing magical about the 350K level. We don't need to adjust for population growth because this indicator is just suggestive and not precise.

EMI: Wachovia Kinda Retreats on Option ARMs

by Anonymous on 4/03/2008 07:35:00 AM

This morning we introduce a new blog feature, the EMI or Escaped Memo Index. The EMI brouhaha was, of course, inaugurated by the famous Chase Zippy Tricks memo, which Chase tells us wasn't "official bank policy." Now Wachovia has a memo out on restricting Option ARMs in some California markets, and the story seems to be that it wasn't really "unofficial," you see, it was just an early draft.

Whatever. The LAT got ahold of it:

Wachovia Corp. signaled that it may no longer offer some Californians the controversial "option ARM" mortgages that give borrowers the choice of paying so little that their balances actually rise.Tanta's Rule of Business Communication: if you decide you'd rather look incompetent and waffle on your policy rather than competently toughing out the whining you know you're going to get, you are, in fact, signalling a certain kind of internal policy. I'd say, brokers, go for Wachovia with those marginal applications. They appear willing to cave in at the slightest touch.

In a memo Monday, Wachovia's top California managers told employees that the loans would no longer be offered in 17 California counties where property values have declined the most, including Riverside, San Bernardino and San Diego, plus the Central Valley.

However, the bank said Wednesday that the memo had been sent prematurely and that it had not decided whether it would stop making the loans.

Then there's this:

Kevin Stein, associate director of the lower-income advocacy group California Reinvestment Coalition, said he had reservations about the marketing of option ARMs as "affordability products," when in fact they were appropriate for only a limited number of borrowers.Possibly this is excellent strategy. If you can credibly threaten Wachovia with the charge of "unfair" lending patterns, you can force it into that corner where it will have to admit that no, these aren't really "good loans."

However, Stein said, since Wachovia argues that its option ARMs are good loans, it should offer them throughout California and not exclude some areas.

Possibly this is more of the kind of thing that makes me want to smack a lot of "advocacy" groups: a definition of "equal access" that means we'll fight for our constituency's right to get fleeced along with everyone else. Yeah, that helps.

Housing Bust Impacts Worker Mobility

by Calculated Risk on 4/03/2008 01:06:00 AM

From Louis Uchitelle at the NY Times: Unsold Homes Tie Down Would-Be Transplants

The rapid decline in housing prices is distorting the normal workings of the American labor market. Mobility opens up job opportunities, allowing workers to go where they are most needed. When housing is not an obstacle, more than five million men and women, nearly 4 percent of the nation’s work force, move annually from one place to another — to a new job after a layoff, or to higher-paying work, or to the next rung in a career, often the goal of a corporate transfer. ...Less worker mobility is kind of like arteriosclerosis of the economy. It lowers the overall growth potential.

Now that mobility is increasingly restricted. Unable to sell their homes easily and move on, tens of thousands of people... are making the labor force less flexible just as a weakening economy puts pressure on workers to move to wherever companies are still hiring.

Perhaps as many as 15 to 20 million households will be saddled with negative equity by 2009. Even if most of these homeowners don't "walk away", there might still be a negative impact on the economy due to less worker mobility.