by Anonymous on 9/04/2007 03:50:00 PM

Tuesday, September 04, 2007

Why S&P Is Not to Blame

Clyde sent me this jewel this morning: S&P answers its critics in "Don't Blame the Rating Agencies":

The fallout over subprime mortgages has provoked a rush to judgment, and some are now blaming the credit-rating agencies for the recent market turbulence. These charges reflect both a misunderstanding of the work carried out by rating agencies, and a misrepresentation of the overall credit performance of securities backed by residential mortgagesTranslation: we only screwed up on the stuff that is obviously risky, and we only misrated the stuff that involves first-loss position. The stuff that is obviously less risky and was never much in danger of taking write-downs is still OK.

Much of the recent commentary has missed several critical facts. For example, our recent downgrades affected approximately 1% of the $565.3 billion in first-lien subprime residential mortgage-backed securities (RMBS) that Standard & Poor's rated between the fourth quarter of 2005 and the end of 2006. This represents only a small portion of the mortgage-backed securities market, which in turn represents a very small part of the world's credit markets. Additionally, our recent downgrades included no AAA-rated, first-lien subprime RMBS -- and 85% of the downgrades were rated BBB and below. In other words, the overwhelming majority of our ratings actions have been directed at the weakest-quality subprime securities.

Ratings are designed to be stable. Unlike market prices, they do not fluctuate on the basis of market sentiment. But they can and do change -- either as a result of fundamental adjustments to the risk profile of a bond or the emergence of new information.Translation: ratings don't change with market sentiment because market sentiment changes only when ratings turn out to be unstable. Or something.

As part of the ratings process, we do engage in open dialogue with bond issuers. This dialogue helps issuers understand our ratings criteria and helps us understand the securities they are structuring, so we can make informed opinions about creditworthiness. We strive to make sure issuers and investors are fully aware of how we determine creditworthiness and believe that all parties are better served when the process is open and transparent.Translation: And we only change our mind when we find out how closed and opaque the process really was, in hindsight.

I can't read any more of this . . .

GM Sales Increase, Ford Sales Decline

by Calculated Risk on 9/04/2007 02:31:00 PM

From the WSJ: GM Sales Increase 6.1% As Ford Sales Tumble 14%

... Ford Motor Co. posted a 14% skid in sales for the month and said it sees higher fourth-quarter production. Toyota Motor Corp. posted a 2.8% sales drop in U.S. sales.

GM said its U.S. sales of cars and light trucks for August rose 6.1% from a year ago and lowered its third-quarter production forecast and sees lower fourth-quarter output.

...

Toyota blamed the credit crunch damping consumer confidence for its drop in U.S. sales in August.

...

Chrysler sales numbers will be released later in the afternoon.

Interagency Statement on Modifications

by Anonymous on 9/04/2007 12:15:00 PM

A deep curtsey to Ramsey for bringing this to my attention.

The Federal Reserve has released an Interagency Statement on Loss Mitigation Strategies for Servicers of Residential Mortgages.

Servicers of securitized mortgages should review the governing documents for the securitization trusts to determine the full extent of their authority to restructure loans that are delinquent or in default or are in imminent risk of default. The governing documents may allow servicers to proactively contact borrowers at risk of default, assess whether default is reasonably foreseeable, and, if so, apply loss mitigation strategies designed to achieve sustainable mortgage obligations. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) has provided clarification that entering into loan restructurings or modifications when default is reasonably foreseeable does not preclude an institution from continuing to treat serviced mortgages as off-balance sheet exposures.2 Also, the federal financial agencies and CSBS understand that the Department of Treasury has indicated that servicers of loans in qualifying securitization vehicles may modify the terms of the loans before an actual delinquency or default when default is reasonably foreseeable, consistent with Real Estate Mortgage Investment Conduit tax rules.3Please join me in congratulating the regulators for this document, and falling to my knees in desperate prayer that this will eliminate some of the confused and backwards reporting on this issue in the financial press. Thank you very much.

Servicers are encouraged to use the authority that they have under the governing securitization documents to take appropriate steps when an increased risk of default is identified, including:

• proactively identifying borrowers at heightened risk of delinquency or default, such as those with impending interest rate resets;

• contacting borrowers to assess their ability to repay;

• assessing whether there is a reasonable basis to conclude that default is “reasonably foreseeable”; and

• exploring, where appropriate, a loss mitigation strategy that avoids foreclosure or other actions that result in a loss of homeownership.

Loss mitigation techniques that preserve homeownership are generally less costly than foreclosure, particularly when applied before default. Prudent loss mitigation strategies may include loan modifications; deferral of payments; extension of loan maturities; conversion of adjustable-rate mortgages into fixed-rate or fully indexed, fully amortizing adjustable-rate mortgages; capitalization of delinquent amounts; or any combination of these. As one example, servicers have been converting hybrid adjustable-rate mortgages into fixed-rate loans. Where appropriate, servicers are encouraged to apply loss mitigation techniques that result in mortgage obligations that the borrower can meet in a sustained manner over the long term.

In evaluating loss mitigation techniques, servicers should consider the borrower’s ability to repay the modified obligation to final maturity according to its terms, taking into account the borrower’s total monthly housing-related payments (including principal, interest, taxes, and insurance, commonly referred to as “PITI”) as a percentage of the borrower’s gross monthly income (referred to as the debt-to-income or “DTI” ratio). Attention should also be given to the borrower’s other obligations and resources, as well as additional factors that could affect the borrower’s capacity and propensity to repay. Servicers have indicated that a borrower with a high DTI ratio is more likely to encounter difficulties in meeting mortgage obligations.

Some loan modifications or other strategies, such as a reduction or forgiveness of principal, may result in additional tax liabilities for the borrower that should be included in any assessment of the borrower’s ability to meet future obligations.

When appropriate, servicers are encouraged to refer borrowers to qualified non-profit and other homeownership counseling services and/or to government programs, such as those administered by the Federal Housing Administration, which may be able to work with all parties to avoid unnecessary foreclosures. When considering and implementing loss mitigation strategies, servicers are expected to treat consumers fairly and to adhere to all applicable legal requirements.

July Construction Spending

by Calculated Risk on 9/04/2007 10:00:00 AM

From the Census Bureau: July 2007 Construction Spending at $1,169.1 Billion Annual Rate

The U.S. Census Bureau of the Department of Commerce announced today that construction spending during July 2007 was estimated at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of $1,169.1 billion, 0.4 percent below the revised June estimate of $1,173.2 billion. The July figure is 2.0 percent below the July 2006 estimate of $1,192.9 billion.

During the first 7 months of this year, construction spending amounted to $657.7 billion, 3.4 percent below the $680.9 billion for the same period in 2006.

...

[Private] Residential construction was at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of $534.0 billion in July, 1.4 percent below the revised June estimate of $541.8 billion.

[Private] Nonresidential construction was at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of $346.0 billion in July, 0.4 percent above the revised June estimate of $344.5 billion.

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.This graph shows private construction spending for residential and non-residential (SAAR in Billions). While private residential spending has declined significantly, spending for private non-residential construction has been strong.

The second graph shows the YoY change for both categories of private construction spending.

The normal historical pattern is for non-residential construction spending to follow residential construction spending. However, because of the large slump in non-residential construction following the stock market "bust", it is possible there is more pent up demand than usual - and that the non-residential boom will continue for a longer period than normal.

The normal historical pattern is for non-residential construction spending to follow residential construction spending. However, because of the large slump in non-residential construction following the stock market "bust", it is possible there is more pent up demand than usual - and that the non-residential boom will continue for a longer period than normal.The question is: Will we see the normal pattern? I think the answer is yes.

MMI: Staying Ignorant in Five Easy Steps

by Anonymous on 9/04/2007 09:16:00 AM

A consensus is emerging in some quarters that a lot of the bad borrowing decisions people appear to have made during the boom had to do with consumers being insufficiently informed. I, who have been doing internet searches on mortgage-related topics since the invention of the internet, and who have learned how to weed out the jillions of "personal finance advice" articles in my quest for actually useful information, am here to tell you that something doesn't add up.

One of these days I'm going to write a nice retrospective post on all the really spiffy advice all those advice columnists handed out to mortgage-wannahaves over the 2002-2006 period, just to see what a "well-informed consumer" might have been expected to have assumed about the world.

Today, though, I'll just content myself with this nice example of post-turmoil wisdom from MarketWatch, whose editors really ought to know better, but consumer-advice-filler-drivel is such a staple of the financial press model that it apparently will take the Second Coming to shock some folks out of it.

PALM BEACH GARDENS, Fla. (MarketWatch) -- You still may qualify for a mortgage, regardless of a shaky credit market. But you need to know the ropes because many lenders have tightened standards. So what should you do if you're buying a home today or you need to refinance? . . .Is it really very helpful to tell people who think they need credit that they should reduce the amount of credit they use in order to get more credit? Bad news, folks: if you have $20,000 in credit card debt and $20,000 in your savings account and you use the money to retire the cards, you will be denied a mortgage loan because in the Brave New World the mortgage lender wants that $20,000 as a down payment. If your credit card debt is trivial, so is this advice. And for the love of God, can we stop talking about what makes you "look risky"? What, "risky" is just some subjective attribute, like "fat in horizontal stripes," that can be fixed by changing your outfit? After all this turmoil, we're still making people think that it's just a matter of appearances and easy steps. MarketWatch, for shame.

Five steps to a mortgage

Before applying for a home loan, consider taking these steps:

1. Pay down credit balances. That will make you look less risky and might help your credit score, suggests Tom Quinn, vice president of scoring for Fair Isaac Corp., Minneapolis. If you have good credit, it may be possible to raise your credit score by asking existing creditors to raise your credit limits. But ask the lender not to pull your credit report to do it. Credit-report inquiries or deteriorating credit can lower credit scores.

2. Get a copy of your credit report from each of the three major credit bureaus. Fix errors and get as much adverse information removed as possible. You're entitled to one free credit report annually from each credit bureau at www.annualcreditreport.com. Read six steps to correct your credit report.I'll forgive the editors of MarketWatch when they produce empirical evidence quantifying the number of people whose difficulty getting a mortgage comes down to credit report errors. You get bonus points if you ask yourself how "fixing errors" became code, during the boom, for fraudulent "credit repair." You get double bonus points for asking how some people became able, easily and without cognitive dissonance, to tell themselves that their debt problems were "all a big mistake."

3. Check licenses of lenders you're considering. This may not be easy because state licensing requirements vary by state and lender. Banks and thrifts can be checked out at www.fdic.gov by clicking on "Institution Directory."Do you yet know whether all depository lenders actually require state licenses? I didn't think so. Do you yet know how many imploded, bankrupt, and criminally-investigated lenders so far this year had perfectly valid licenses? I didn't think so.

4. Shop several lenders. Don't assume if you get one quote of an unusually high interest rate, all will be high. Negotiate lower rates and seek removal of unnecessary fees.Do you know what "unusual" is? Do you know what fees are "necessary"? Please analyze and evaluate your "negotiating" strength in a credit crunch. You can use the back of this paper if you need more space. (Hint: it's called a "credit crunch" when you have no position from which to negotiate because you need a loan more than the lender needs to make one.)

5. Consider that interest rates and terms may change daily. Also, a low interest rate could mean more upfront points or added fees. Get all pricing information in writing before obtaining a written commitment for your loan. Get a commitment letter directly from the lender who's financing the mortgage, which may be different from the loan originator.This one may be my favorite. You aren't likely to get a written price quote until your loan has been underwritten these days. That means that the written price quote is in the commitment letter. It still isn't a "rate lock" until you get a "rate lock agreement." Much, much more to the point is that a "commitment letter" commits the lender to lend at the specified terms. It does not commit the borrower to borrow. You are not obligated for diddlysquat until you sign something with "Note" at the top and "I promise to pay" somewhere in the first line. We have heard story after story about people who didn't think they could "back out" when they were confronted with closing documents that didn't look right. Helpful advice might involve explaining that issue.

I conclude that the authors of this article have never been any closer to the actual mortgage business than standing around taking up space in my lobby, eating my LifeSavers and reading my back issues of House Beautiful, before getting tired of that and going home to surf the web for stupid "consumer advice" articles from 2004 that can be rehashed into filler for today's column.

MarketWatch editors: Now do you understand why I get so "mercurial" when you do this?

Monday, September 03, 2007

Shiller on Housing

by Calculated Risk on 9/03/2007 01:03:00 PM

On Bloomberg Video: Shiller of Yale Says U.S. Home Prices May Fall `Substantially'. (hat tip Houston)Click image for video.

September 3 (Bloomberg) -- Robert Shiller, chief economist at MacroMarkets LLC and a professor at Yale University, talked with Bloomberg's Kathleen Hays on Sept. 1 about the outlook for the U.S. economy and housing prices. (Source: Bloomberg)

More Leamer

by Anonymous on 9/03/2007 12:50:00 PM

This is another snippet from the Leamer paper CR discusses below, in which Dr. Leamer argues that if we had nothing but economists on our side, we'd never get rid of Voldemort:

We love our homes. We don’t love our investments in General Motors or IBM, and when the stock market sends us the daily message that share prices have plummeted, we reluctantly accept that unwelcome reality. Homes are different. We have a close personal relationship with our homes. When the market is hot, buyers stream by our front doors proclaiming that they love our homes even more than we do by offering prices beyond our wildest dreams. Charmed by that flattery, many of us sell our loved ones, confidant that we have turned our homes over to people who will treat them well. Thus rising prices and high sales volumes. When the market cools, however, only a few prospective buyers come to our front doors, and those prospective buyers bring a most unsettling message: “We know you love your home, but it isn’t worth nearly as much as you think.” That can be a deal-breaker for female owners, but the clincher for males is the fact that their idiot neighbor sold his home for $1 million just last year, and the male owner is not going to take a penny less than that. It doesn’t matter what the market thinks. This house is worth $1million. Period.No, I'm not here to point out that Leamer seems to have attended the Larry Summers School of Unwise Rhetoric About Genderalizations.

Housing hormones, both estrogen and testosterone, make owners very unwilling to sell into a weak market and that unwillingness tends to keep the prices of homes actually sold high while greatly reducing the volumes of homes sold. What we observe are not market prices but sellers’ prices.

If you don’t like this love story, another good one is that sellers look backward, remembering what they or their neighbors paid, but buyers look forward, wondering what the house might be worth in a couple of years. Positioned in time looking in different directions, when the market is rising, owners estimate the value less than prospective buyers, and a sale occurs, but when the market is falling, the owners remember the good old days of high prices, and the buyers are thinking about a better deal in a couple of months. Then there is no transaction, unless it is at the high sellers prices. A third story comes from the behavioral economics: It’s loss aversion.7 As long as I don’t sell my home, I can comfortably maintain that it is worth what I paid for it.

Of course, economists have no room in their models for love, hope, or the psychology of loss. . . .

I was actually going to observe that economists spend some time hanging out in a mortgage shop. You will learn everything you need to know about the effects of love, hope, and the psychology of loss on economic decisions.

More Papers from Jackson Hole Conference

by Calculated Risk on 9/03/2007 10:54:00 AM

Here are a couple more papers presented at the Jackson Hole conference. I'll be posting excerpts with comments from these papers during the week.

Housing and the Monetary Transmission Mechanism, by Frederic S. Mishkin, Fed Board of Governors.

Comments on Housing and the Monetary Transmission Mechanism, Professor James Hamilton, UC San Diego.

There was apparently quite an interesting discussion at the symposium of MEW (mortgage equity withdrawal) and the impact on consumer spending. Martin Feldstein argued that MEW has had an important impact on consumer spending. So did Professor John Muellbauer. Muellbauer presented a paper modeling the interaction between house prices, credit availability, and spending. Apparently Muellbauer found that the housing wealth effect has grown sharply in the US due to the recent period of easy credit.

I'll have more as soon as soon as the papers are available online at the Jackson Hole symposium site.

As an aside, Business Week mentioned us this week (see Blogspotting: Loan Smarts).

Sunday, September 02, 2007

Leamer on Housing and Macroeconomics

by Calculated Risk on 9/02/2007 09:05:00 PM

Here is the paper Professor Leamer (UCLA Anderson Forecast) presented at the Jackson Hole conference: Housing and the Business Cycle (Hat tip Cal). Leamer is one of the better economic forecasters, and he has an enjoyable writing style.

Leamer starts by noting that most academic macro economists typically ignore residential investment:

... if you look up “real estate” in the index to Mankiw’s(2007) best selling Principles of Macroeconomics, you will find real exchange rates, real GDP, real interest rates, real variables, and even reality, but no real estate. Under “housing” you will find a reference to the CPI and to rent control, but no reference to the business cycle. I have not been able to find any macroeconomic textbook that places real estate front and center, where it belongs.The joke is Mankiw couldn't forecast his way out of a paper bag. However many of the better private sector forecasters (like Leamer and Paul Kasriel at Northern Trust) know that residential investment is the best leading indicator for the U.S. economy. Leamer notes the residential investment is a small part of long run growth, but that the contribution of residential investment to "US recessions is huge!"

...

Likewise, the index to James H. Stock and Mark W. Watson’s edited volume, Business Cycles, Indicators and Forecasting, has no references to residential investment or to housing. Housing is treated with the same level of interest that housing starts has in the Index of Leading Indicators: one of many things that might predict a recession, about as interesting as x7 in the list x1, x2, x3, ..., x10.

...

Something’s wrong here. Housing is the most important sector in our economic recessions ...

Leamer also points out the common temporal pattern of an economic slowdown:

First homes, then cars, and last business equipment.Sound familiar? I've covered this many times, pointing out that business investment in equipment and software and structures lags residential investment. Read the paper, there is a tremendous amount of detail.

Leamer also has some data from the Great Depression:

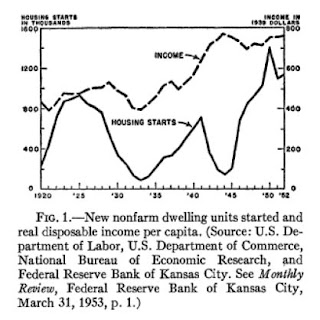

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.The Great Depression: Housing Again!A little poke at Bernanke!

The housing starts data available from the Census Bureau begin in 1959 and leave us wondering what happened earlier, but in searching for references I ran across the image to the right of the earlier data in Ketchum(1954). Look at that: housing starts declined beginning in 1925! Industrial production didn’t begin its nosedive until July 1929 and the Dow Jones Average peaked in October 1929. How weird is that!

Problems in housing led the great depression by full three years. Without doing the hard work to confirm, it seems possible that the increase in the discount rate in 1928 was very hard on an already weakened housing sector, and set in motion the events that led to the Great Depression, dropping housing starts dramatically from over 900 thousand in 1925 to under 100 thousand in 1933. But, of course, I must defer to Bernanke’s(2000) Essays on the Great Depression, which does not emphasize housing.

But Leamer still doesn't expect a recession:

The historical record strongly suggests that in 2003 and 2004 we poured the foundation for a recession in 2007 or 2008 led by a collapse in housing we are currently experiencing. Only twice have we had this kind of housing collapse without a recession, in 1951 and in 1967, and both times the Department of Defense came to the rescue, because of the Korean War and the Vietnam War. We don’t want that kind of rescue this time, do we?So Leamer expects an extended period of sluggish growth. I disagree with Leamer somewhat: I think a recession (not severe) is likely. Of course Leamer notes "this is largely uncharted territory."

But don’t worry. This time we don’t need the DOD to save us. This time troubles in housing will stay in housing. It’s because manufacturing has done an “L” of a job. An official recession cannot occur without job loss, [and the] sectors with volatile employment are manufacturing and construction ...

Look at manufacturing. It’s V, V, V in every recession - a sharp drop in jobs and a sharp recovery. The 1990 recession was different. That was a U. But in the 2001 recession we got an L! [note: no recovery in jobs] Though this is largely uncharted territory, it doesn’t look like manufacturing is positioned to shed enough jobs to generate a recession. And without the job loss, expect the housing adjustment to be shallower but more long-lasting.

Bear Stearns Fund's "Qualified Investors"

by Anonymous on 9/02/2007 09:16:00 AM

The redoubtable Gretchen Morgenson reports on the liquidation of the infamous Bear Stearns hedge funds. We discover that in 2005 at least one of the funds waived its normal $1MM limit to attract investors with as little as (ahem) $250,000 to invest. (It's still not clear to me what the total net worth requirement was for the investor putting only $250,000 into the fund.) Anyway, our anecdote without which we cannot live:

Ronald Greene, 79, a retiree in Northern California, is one investor watching the Bear Stearns case closely. Greene lost $280,000 in the Bear Stearns High Grade Structured Credit Strategies Fund and says he will join a suit that has been filed against the firm. He contends that Bear Stearns duped him with assurances that the fund's high-quality investments would protect holders against market and credit risks.I think I now understand why so many of my conversations with people during 2005 were at cross-purposes. I would never have guessed that anyone using the phrase "preservation of principal" would be thinking of hedge funds as the vehicle of choice.

Hedge funds are theoretically open only to institutional investors and extremely wealthy individuals, who are deemed savvy and well heeled enough to assess and weather complex risks. But documents from Greene's files show that Bear Stearns Asset Management allowed investments of $250,000 in its fund, considerably smaller than the typical $1 million minimum for many hedge funds.

On July 20, 2005, Greene received an e-mail message from his broker at a small regional firm, with the following header: "Bear Stearns High-Grade Structured Credit Strategies Fund will accept smaller investments this month on a limited basis." Noting that the fund was temporarily reopening on Aug. 1, 2005, the message said that for investors who "do not have $1,000,000 to invest, the fund will accept a limited number of clients this month for 500K and perhaps 250K."

The message went on to note the fund's stellar performance: up a cumulative 29.4 percent since its October 2003 inception, and no down months.

Greene, a former engineer, said he had invested in several hedge funds in recent years, aiming to preserve his principal. Most of the funds have worked out well, he said, producing slightly better-than-market returns with little volatility. He estimated that he had $600,000 to $800,000 invested in hedge funds.

He invested in the Bear Stearns fund in October 2005, and he said the fund appealed to him because its returns of about 1 percent a month did not seem to fall into the too-good-to-be-true category.

I have a question. Mr. Greene thought 1% a month didn't sound that unreasonable. By my back-of-the-envelope calculations that's 12% a year. From securities backed by home mortgages.

I conclude that Mr. Greene must hang out a lot with people who regularly pay 12% mortgage rates. This gave him the mistaken impression that the return on CDOs has something to do with just passing through interest payments, and not outrageous levels of gearing and risk concentrations.

Right. I know a lot of people who have nearly a million dollars invested in hedge funds whose friends all have the most expensive subprime mortgages ever originated (remember how high 12% was in 2005; that's a sub-sub-subprime.)

Please do not misunderstand me; I am not making excuses for Bear Stearns, nor am I suggesting that Mr. Greene deserves to lose his money. I am simply somewhat puzzled over our inability, now that the curtain has been drawn back on how all this worked, to ask these people how they thought investing in CDOs to "preserve principal" at 12% was going to work. There's trusting your broker--obviously that gets to be a problem--and then there's just plain old having some idea about what your broker is doing.

It begins to sound like Mr. Greene would have plunked his money down in the Tralfamadore Anti-Matter-Indexed Mystery Investment Vehicle (incorporated on Mars) if someone had said that the returns were "only" 1% a month. Of course it's understandable that Mr. Greene wanted 1% a month, because interest rates were so low that it was hard to find yield in instruments that involved other people paying interest . . .