by Tanta on 7/24/2008 09:37:00 AM

Thursday, July 24, 2008

Downey's "Retention Mods" Performance

Well, yesterday was quite the odd day. I was having a late afternoon nap when I suddenly awoke, heart pounding and skin crawling, with that horrible spooky sense of being watched. I decided it was a bad dream, made a cup of tea, and wandered over to the computer, only to discover that my co-blogger had just a few minutes earlier put up a post letting us all know that the FDIC is going to be keeping its eyes on bloggers.

There's only one thing for it, then. If the FDIC is going to be worrying about the bloggers, the bloggers are going to have to be worrying about the insured depositories. I don't know that that's an ideal setup, exactly, but someone has to worry about the banks and thrifts, not just about bad PR for the FDIC, and if Sheila Bair is going to ruin my naps I'm going to have time on my hands.

Which brings us to Downey Financial, who visited the confessional this morning. It was pretty ugly. What we got, for the first time as far as I can remember (I nap a lot these days, you know, or at least I used to), is some post-modification performance information on the infamous "retention modifications."

If you remember, Downey got everybody a little fired up back in January when it announced that its auditor was making it restate its Non-Performing Asset (NPA) numbers for the second half of 2007. Downey had put in place a program to offer "market rate" modifications to performing borrowers in its loan portfolio. These were, apparently, mostly Option ARM borrowers whose rates had adjusted to pretty high levels. Downey modified them into amortizing ARM loans at the same interest rate that a new ARM borrower would have gotten. Because there was not a below-market rate given to these borrowers, and because they were current at the time of modification, Downey decided it did not need to count these loans as "troubled debt restructurings," which would mean including them in the NPA category. However, KPMG told Downey that the loans did indeed need to be considered "troubled debt restructurings," for a very specific reason: Downey did not re-underwrite these loans at the time of modification to verify and document that the "market rate" given to the borrowers was truly the rate that a new borrower of the same credit quality would have gotten. Downey agreed to count all of these "retention mods" as NPA until each borrower had made six consecutive payments under the new loan terms. Ever since then, Downey has been reporting separate numbers for total NPA including the retention mods, plus NPA without the retention mods. They clearly believe that having to include the retention mods in NPAs makes their NPA number look worse than it "really" is. Whatever that means.

In today's press release, we got some additional information about the performance of these loans:

To the extent borrowers whose loans were modified pursuant to the borrower retention program are current with their loan payments and included in non- performing assets, it is relevant to distinguish those from total non- performing assets because, unlike other loans classified as non-performing assets, these loans are paying interest at interest rates no less than those afforded new borrowers. At June 30, 2008, $548 million or 82% of such borrowers had made all loan payments due. Accordingly, the 15.50% ratio of non-performing assets to total assets includes 4.34% related to performing troubled debt restructurings, resulting in an adjusted ratio of 11.16%.So. The "retention program" has been in place for one year now. If I am reading this correctly, a total of $1.015 billion in loans have been modified under this program. $347 million have made at least six consecutive on-time payments and are no longer included in NPA. Of the $668 million still in NPA, $548 million have made all payments due so far (that might be less than six, since some of these mods will be less than six months old).

Through June 30, 2008, $347 million of loans modified pursuant to our borrower retention program have been removed from non-performing status because they met the six-month payment performance threshold. Of all loans modified pursuant to the borrower retention program, including both those classified as non-performing as well as those removed from non-performing status, 87% have made all payments due.

This means that of a group of modified loans that are no more than one year old, 87% are performing. If you remove the oldest performing loans from that group--the ones that have had six payments actually due and have made those payments--you get 82% performing loans. A delinquency rate of 13-18% in the first year would probably be something to be proud of if these were "classic" troubled debt restructurings--namely, workouts of delinquent loans that required below-market interest rates to result in payments the borrower could afford.

But Downey tells us these "retention" mods were done for borrowers who were current on their loans at the time of modification, and who were given rates no better or worse than market. The very idea of a "retention" program, of course, is that (in theory at least) these are borrowers whom you don't want to refinance away from you with another lender, because they're good borrowers. You "retain" them by offering them a less expensive alternative to refinance, namely a modification that keeps the loan with the same lender and servicer.

And 13-18% of these "keepers" went bad within a year or less of a modification that supposedly improved their risk profile? Perhaps people are getting used to seeing such high delinquency rates on subprime and "worked out" loans that figures like this seem normal. But these are supposed to be prime loans, and that level of early delinquency or default in a book of "retention" mods is just awful. Downey says these borrowers got the same modified rate and terms that a new refinance borrower would have gotten. Were they expecting that 13-18% of their newly-originated refinance transactions would be delinquent in the first year?

If nothing else, I'd say this demonstrates a good call by KPMG. Downey called these "retention" mods--implying that they were the kind of high-quality borrowers you don't want to lose to the competition--and failed to re-underwrite the loans to verify that claim. The results of this program suggest to me that it was less a classic "retention" program than a pre-emptive strike: Downey made a big effort to modify as many of its then-current Option ARMs as it could into better loan terms, not because they were the kind of borrowers you necessarily want to "retain" but because they were probably not going to get a decent refi anywhere else and if they'd stayed in the Option ARM program the delinquency rate would likely have been worse than 13-18% a year later.

I don't actually think that a "proactive" modification program is necessarily a bad thing. But I think calling it a "retention" program is disingenuous at best, and I think that Downey's experience is proving the point that it really does matter whether you re-underwrite those loans before you modify them. But then, forcing outfits like Downey to call these programs "pre-delinquency workouts because letting them ride is too dangerous" programs rather than "retention" programs would probably spook people, and we know the FDIC doesn't want that.

Monday, June 30, 2008

Wachovia Waives Refi Fees for Pick-A-Pay, Discontinues NegAm Products

by Calculated Risk on 6/30/2008 02:24:00 PM

Note: Pick-A-Pay is Wachovia's Option ARM (adjustable rate mortgage) product with a NegAm (negative amortization) option.

Press Release: Wachovia Corporation Announces Assistance for Pick-A-Pay Customers

Effectively immediately, Wachovia is waiving all prepayment fees associated with its Pick-A-Pay mortgage to allow customers complete flexibility in their home financing decisions.Obviously Wachovia wants people to refinance out of their current Option ARMs. The NegAm products are really hurting Wachovia.

...

Additionally, for all new loan originations, Wachovia is discontinuing offering products that include payment options resulting in negative amortization.

Wednesday, June 18, 2008

Option ARMs: Then What?

by Tanta on 6/18/2008 09:24:00 AM

Bloomberg reports:

June 18 (Bloomberg) -- Wachovia Corp., which ousted its top executive after estimating it may lose more than $4.5 billion on adjustable-rate home loans, will start calling would-be borrowers to explain the risks of such mortgages.Unfortunately, we do not find out what Wachovia is going to do if it establishes that, in fact, the customer does not understand the key features of the product. Refuse to make the loan? Fire the broker? Keep explaining the difference between scheduled recast and balance cap, or uncapped rate with capped payment, until the borrower finally claims to understand you just to get you off the phone? How will success here be documented in the loan file? Does the borrower have to get at least 6 out of 10 on a Pick-A-Payment Quiz? Or will Wachovia grade on a curve?

Wachovia is contacting applicants through independent mortgage brokers to ensure ``the customer understands the key features of the Pick-A-Payment loan product,'' according to a June 11 memo from Tim Wilson, head of loan origination at the Charlotte, North Carolina-based company. The loans let borrowers defer part of their monthly bills.

Furthermore, how, exactly, does Wachovia intend to run a profitable wholesale mortgage business by duplicating more and more of the broker's functions? Will borrowers end up paying more fees to cover the broker's "counseling" labor and then the wholesaler's "counseling" labor on top of that? Is there some incentive for brokers to fully explain this product, or will they simply start relying on the wholesaler to cover the "mechanics of the loan" part? And who are these folks in Wachovia's back room who are talking to these borrowers? The sacred cow myth in the business is that only professional salespeople with Professional Sales People Skills can work with customers at the point of sale, which is what justifies their big commissions. You can't let back-room weenies (like me) talk to the

Let me guess. Wachovia is going to find out eventually that the Option ARM is valid only as a boutique product for a very highly selected group of financial sophisticates and private banking clients, all of whom are going to be found in your retail channel, not your broker channel, and that its "natural" volume is probably around 1.00% or less of your mortgage business. Funny, isn't it, that six or seven years ago we already knew that?

Saturday, June 14, 2008

ARMs: The Next Wave of Delinquencies

by Calculated Risk on 6/14/2008 03:27:00 PM

Mathew Padilla at the O.C. Register has an interesting piece on rapidly rising delinquencies in Orange County, CA: Orange County’s mortgage market distress could soon top the U.S..

The report said O.C.’s delinquency rate of 3.14 percent, was less than California’s 4.34 percent and the nation’s 3.23 percent.Here are some comments from Keith Carson, a senior consultant for TransUnion, on why the delinquency rates are rising quickly in Orange County:

But, unfortunately, the county’s delinquency rate is rising more quickly than for both the state and nation.

In Orange County, ... the rate at which you are accelerating is reason for concern. I think that is probably a function of the number of adjustable-rate loans that were made in Orange County in the 2005 to 2006 time frame. Some of those have reset (the interest rate has increased) to the point where occupants can’t afford the payments.This is not a subprime problem. The reason the delinquency rate is rising rapidly in Orange County is because homes are very expensive, and a large number of recent home buyers used ARMs, especially Option ARMs, as affordability products.

...

I think it is mostly due to the price of homes in California. There were a lot more ARMs used so people could afford to get into a home. For a lot of people the only way they could get into a home was with an ARM.

Now that the interest rate is increasing - and in some cases the loans are hitting the maximum allowed principal ceiling - these loans are no longer affordable. Since these same homeowners have negative equity, selling the home is not an alternative.

The important point here is that delinquencies are starting to increase rapidly in middle to upper middle class neighborhoods where buyers used "affordability products" to buy more house than they could really afford.

We are all subprime now!

Sunday, June 08, 2008

Option ARMs: Moving from NegAm to Fully Amortizing

by Calculated Risk on 6/08/2008 10:00:00 AM

From BusinessWeek: The Next Real Estate Crisis

[T]he next wave of foreclosures will begin accelerating in April, 2009. ... hundreds of thousands of borrowers who took out so-called option adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs) will begin to see their monthly payments skyrocket as they reset.

...

According to Credit Suisse, monthly option recasts are expected to accelerate starting in April, 2009, from $5 billion to a peak of about $10 billion in January, 2010.

...

The loans automatically recast after five years, but many will recast sooner as loan balances hit specific principal caps—typically between 110% and 125% of the initial loan amount.

Click on image for Business Week graph in new window.

Click on image for Business Week graph in new window.This graph from Credit Suisse (via Business Week) makes a key point. Many of the Option ARMs will recast sooner than originally scheduled, because the loan amount will have hit the principal ceiling (usually 110% of the original loan amount).

Tanta explained this in Negative Amortization for UberNerds:

[Once the loan hits the principal ceiling], the loan must become a fully amortizing loan—no more minimum payment allowed, all payments must be sufficient to pay all interest due and sufficient principal to amortize the loan over the remaining term.What matters for the housing market is the gray bars - and we are just starting to see the impact on delinquencies of homeowners moving from NegAm payments to fully amortizing payments on their Option ARMs.

The percent of original balance limitation, in other words, marks the day that neg am is no longer an option for the borrower, and the loan has to start paying down principal from here on out—the borrower is “caught up,” and never again allowed to “get behind.”

...

Note that the loan remains an ARM, even though it is now no longer a neg am ARM. That means that the borrower’s payment can still increase or decrease at future rate change dates. It will simply be, from here on out, an increase or decrease from one fully-amortizing payment to a new fully-amortizing payment.

emphasis added

And, finally, the blue bars tell us when these homeowners obtained their loans - usually 5 years before the scheduled recast. Since the peak is in 2011, we know that most of these homeowners bought or refinanced from 2005 through early 2007. Therefore, with falling house prices, most of these homeowners are underwater (owe more than their homes are worth), and selling or refinancing will not be a viable alternatives.

Wednesday, May 21, 2008

World Savings Option ARM Training Video

by Tanta on 5/21/2008 11:56:00 AM

Channel 5 in San Francisco got its hands on some "training videos" used by World Savings--now owned by Wachovia--to teach brokers and loan officers how to originate their "Pick-A-Payment" negative amortization ARM. It's pretty disgusting:

But what concerns [housing advocate Maeve Elise] Brown even more was the way World Savings employees were instructed to answer questions about the minimum payment on those option ARM's.Unfortunately, I don't think very many borrowers probably asked that minimum-payment question. To think that those few who did would be fobbed off with the comment "it's optional" is nausea-inducing. It also strongly suggests, of course, that borrowers who didn't ask that question didn't find the brokers volunteering the information that making the minimum payment would increase the balance.

"So if I'm paying that minimum payment, I'm not actually putting a dent in my principal though right? My principal and interest they're just going to keep climbing up right?" the borrower asks in the video tape. "It's optional," the broker in the video replied.

"What kind of answer is that?" said Brown after watching the video. "The answer would really be 'Yes.' That's the right answer, that to me would be the true clear straightforward truthful simple answer."

And in still another scenario, the video instructs brokers to explain those loans. "Why would I offer a loan that has a negative amortization?" the broker asked. The World Savings representative replied: "Most brokers refer to them as negative amortization, but we try to use the words a little more user friendly, 'deferred interest.'"

(Hat tip to checker!)

Thursday, April 03, 2008

EMI: Wachovia Kinda Retreats on Option ARMs

by Tanta on 4/03/2008 07:35:00 AM

This morning we introduce a new blog feature, the EMI or Escaped Memo Index. The EMI brouhaha was, of course, inaugurated by the famous Chase Zippy Tricks memo, which Chase tells us wasn't "official bank policy." Now Wachovia has a memo out on restricting Option ARMs in some California markets, and the story seems to be that it wasn't really "unofficial," you see, it was just an early draft.

Whatever. The LAT got ahold of it:

Wachovia Corp. signaled that it may no longer offer some Californians the controversial "option ARM" mortgages that give borrowers the choice of paying so little that their balances actually rise.Tanta's Rule of Business Communication: if you decide you'd rather look incompetent and waffle on your policy rather than competently toughing out the whining you know you're going to get, you are, in fact, signalling a certain kind of internal policy. I'd say, brokers, go for Wachovia with those marginal applications. They appear willing to cave in at the slightest touch.

In a memo Monday, Wachovia's top California managers told employees that the loans would no longer be offered in 17 California counties where property values have declined the most, including Riverside, San Bernardino and San Diego, plus the Central Valley.

However, the bank said Wednesday that the memo had been sent prematurely and that it had not decided whether it would stop making the loans.

Then there's this:

Kevin Stein, associate director of the lower-income advocacy group California Reinvestment Coalition, said he had reservations about the marketing of option ARMs as "affordability products," when in fact they were appropriate for only a limited number of borrowers.Possibly this is excellent strategy. If you can credibly threaten Wachovia with the charge of "unfair" lending patterns, you can force it into that corner where it will have to admit that no, these aren't really "good loans."

However, Stein said, since Wachovia argues that its option ARMs are good loans, it should offer them throughout California and not exclude some areas.

Possibly this is more of the kind of thing that makes me want to smack a lot of "advocacy" groups: a definition of "equal access" that means we'll fight for our constituency's right to get fleeced along with everyone else. Yeah, that helps.

Wednesday, March 19, 2008

HUD Proposal on Good Faith Estimate I: The Context

by Tanta on 3/19/2008 04:48:00 PM

HUD has just released yet another proposal for changing the disclosures required under the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act (RESPA), a federal law that is implemented by regulations promulgated by HUD. I’m not terribly impressed by the proposal, but it’s hard to say why without a lot of background rambling. So I’m going to ramble. Those who aren’t up for it should skip this. In a future post, I’ll get into the specifics of what I don’t like about the proposed new GFE.

A quick recap: RESPA requires a lot of things, two of the most important of which being the Good Faith Estimate of settlement costs, known as the GFE, and the HUD-1 or HUD-1A Settlement Statement, the exact accounting of closing costs and settlement charges given to borrowers when the loan closes. The GFE is given at application. The idea when RESPA was first enacted was to prohibit lenders from giving low-ball estimates of costs up front, only to shock the borrower with a lot more costs at closing, when it was often “too late” for a purchase-money borrower (or a refi borrower with a rate lock expiring) to back out. The estimates of costs on the GFE have to match what’s on the HUD-1 within a certain tolerance, or else you have a regulatory problem. The GFE/HUD-1 rules have been around for decades. In the last few years HUD (the agency, not the document) has made a few attempts to revise them, all of which have failed for one reason or another. The current proposal is just the most recent in a long line of unsuccessful attempts to get control of the disclosure of financing costs to borrowers, most specifically in the case of brokered loans (although the new rules would apply to retail lenders as well).

In some ways, what HUD is doing is formalizing the brokered application model into the RESPA disclosure scheme, a decade or two after certain problems and concerns first arose. One of the troubles that wholesale lenders have had for a long time is making sure they’re meeting RESPA rules for when the GFE has to be given to the applicant; the rule has for a very long time been that the disclosures must be provided within three business days of “application.” But what is the date of “application”? The date the broker takes an application from a borrower, or the date the wholesaler receives an application from the broker? From the borrower’s perspective, of course, this is easy: it’s the day you gave the broker sufficient information to complete the application. This implies that it is the broker’s job to provide you with the GFE. (And for what brokers charge borrowers, you might well think providing a written estimate of closing costs isn’t so much to ask.)

But the wholesaler has always had a problem here, because the wholesaler is going to close that loan and the wholesaler is going to have the “RESPA risk,” or the risk that the disclosure was inaccurate or not provided in a timely fashion. As with other things, it has never especially mattered that it might be the broker’s “fault”; brokers haven’t got the money to make you whole on fines, penalties, recissions and re-closings of loans, or sales of loans as “scratch and dent” because the higher-paying investors won’t buy a loan with iffy RESPA docs in the file. So wholesalers developed this habit of simply “redisclosing” or providing a GFE for the borrower within three days of getting the application from the broker, even if the broker had already supplied one. This was supposed to assure that whatever the broker did, the wholesaler complied with RESPA and made sure that the fees disclosed on the GFE were fees the wholesaler was comfortable with charging on the final settlement statement.

That meant several things, one of which is that borrowers were usually waiting the three full business days to get a GFE, and were paying application fees before getting one. At minimum, borrowers were paying for credit reports, since in these days of risk-based pricing, you don’t get a GFE until we know what your rate/points are, and we don’t know that (even approximately) until we know what your FICO is. RESPA, which predated such practices, was based on the assumptions of an older way of doing business, in which an application could be submitted and an estimate of costs given well before any “processing” on a loan, like ordering a credit report, commenced. Of course, once a borrower has paid a fee to get a GFE, it’s much less likely that borrower will “shop around” and pay several other lenders the same fee to get alternative GFEs.

It also pretty much erased—and then some—the wondrous efficiencies we had achieved at least since the mid 90s with cool technology. I am hardly the only person to have spent centuries of her life she’ll never get back in meetings and task forces and committees and piles of documentation and user testing working on rolling out “point of sale” (POS) technology that would allow loan officers armed with laptops and a portable printer to take a complete application right there, on the granite countertops, at the open house, and print out a pretty, complete GFE, right there on the granite countertops. With a dial-up connection, the LO could run the loan through an AUS and even hand out a commitment letter (subject to getting the appraisal and so on). Ah, the glorious days of progress, when we congratulated ourselves on providing a GFE to applicants in three business minutes.

It’s not exactly an accident that the acronym “POS” means both point-of-sale and piece of . . . stuff. There were any number of problems with the POS technology, not the least of which was those portable printers, which were “portable” as long as you didn’t expect them to be “printers” and vice versa. Many lenders got gung-ho about giving their loan officers the authority to issue commitment letters at POS, and found themselves committed to making loans that the underwriting department wouldn’t have approved on PCP. There was also, it transpired, a little problem with those pesky consumers. It turned out that what they really wanted out of life wasn’t always to stand around at an open house giving personal information to an LO and getting not just “estimates” but a commitment letter they were feeling pressured to sign without any cooling-off period or shopping around. As is often the case, the industry told itself customers were really interested in speed, when in fact the industry was really interested in speed and the customers had to be made to see reason about it. I can remember at one point a local competitor of mine proudly announcing it didn’t offer that “high-pressure tactic” of POS technology, and that competitor took a lot of our business.

The issue for retail originators was having an LO out there like a loose cannon with a laptop, making quickie commitments often based on quickie evaluation of the borrower’s seriousness or capacity. Those commitments were always supposed to be “subject to” finally getting all the real documentation and verifications and so on, but some loan officers figured out that such a heavily-conditioned commitment is hardly much of a commitment—it just encouraged people to “shop around”—and so “competitive pressures” led to leaving out a lot of those conditions. In fact, at least one of us believes that the “stated income/stated asset” phenomenon really began here. The Official Story in the industry is that it grew out of perfectly reasonable ways to underwrite self-employed borrowers with complicated financial lives, and somehow spread to W-2 borrowers with a single checking account when we weren’t looking. I don’t personally remember it happening that way.

The issue for wholesale lenders was even worse, since the brokers often weren’t quite sure which wholesaler they’d be closing this loan with—it would depend on who paid the richest premium, often, and that couldn’t be established until they got back to the office and checked rate sheets. So the brokers would hand out GFEs based on wild-arsed guesses of the fees required by the wholesalers, leading to endless situations in which the fees charged on the final settlement statement were pretty far off the original estimate, leading to endless situations in which regulators and consumer attorneys had to remind everyone what the “good faith” part of GFE meant. That was when the broker actually bothered to hand out a GFE, or do it within the holy three days. The wholesalers concluded it would be better for them to “re-disclose” on receipt of the application package (later, the electronic submission) from the broker. Aside from the monumental customer confusion that creates—which GFE is the “real one”?—it began to dawn on at least a few wholesalers that duplicating too much of the work the broker was supposed to be doing was approaching the same operating cost structure of a retail lender. It wasn’t just the disclosure issue, after all. You had to re-verify the broker’s verbal verification of employment and order (and review) a field review appraisal to reality-check the appraisal you let the broker order and so on until there wasn’t much the broker did that you didn’t also do.

The obvious answer to that was to make the borrower pay for it all. You began to find GFEs showing “underwriting fees” and “document preparation fees” all over the place, for instance. Now, underwriting your loans and drawing up your closing documents used to be considered basic overhead, you know, and lenders covered that in an origination fee charged to borrowers (or in the margin on the interest rate). The only time you ever charged a “doc prep fee” to a borrower was a situation in which you actually had to draw up unusual, complex documents—like a convoluted trust agreement or one of the gnarlier “hold harmless” agreements—that you needed to actually pay outside counsel for. You never charged anyone a separate fee for standard mortgage docs; that was like charging them for the air conditioning in the closing room. But in the wholesale model, you had to find some way for the broker to draw up GFEs and the wholesaler to then do it again and the whole thing to remain profitable for everyone. All kinds of other things, like flood hazard determinations and tax service contracts, that we always had to obtain for loans but that we always just covered out of the origination fee, started to appear as separate items on the GFE and HUD-1.

It was and still is argued all over the place that these practices are really pro-consumer, since it’s a clearer “itemization” of the real cost of credit than some all-in “origination fee” or “broker fee.” Had the origination fees shrunk proportionally to the newly added itemized fees, that might have been plausible. But in way too many cases, you were paying the same origination point you had always paid, plus $40 for a flood cert and $75 for a tax service contract and $100 for doc prep and on and on and on. In fact, you were paying so much in fees at closing that you were in real danger of not being able to scrape up that much cash—or increase your loan amount enough—to cover them and get a loan closed. This was (pre-RE bubble) a huge problem with refis. Refis are brokers’ bread and butter in low-rate environments, and it’s hard to convince people to refi for a 25 bps drop in rate—which people did—with that nasty cash requirement.

The solution was obvious: find a wholesaler who is willing to price a higher interest rate at a “premium,” and use that premium to “credit” the borrower, or to do the now-ubiquitous “no cost closing.” Of course it’s plenty of “cost”; it’s really just a “no-cash” closing. Obviously there are only certain actual historical rate environments in which this kind of thing will work in the prime lending world: if you’ve got borrowers wanting to “take advantage” of new, lower interest rates to refinance, you can’t always charge them the highest rate out there in order to produce enough premium to pay inflated closing costs with. It’s the kind of thing that might work in the beginning of a steep rate drop, like the 2002-2003 period, when existing loans on the books had a high enough interest rate that they could refinance into a current “premium” rate and still show a rate reduction. The trouble is, if you do too much of that on a wide scale—and the turnover in the entire nationwide mortgage book in 2002-2003 was enormous--it gets harder to do it again. Once the prime mortgage book had “reset” itself to very low current rates via a refi boom, it was hard to tempt them with a premium to current market, unless fixed rate mortgages hit 4.00%. They didn’t, so someone had to invent a mortgage product that seemed like a lower rate to borrowers but that also paid enough hefty premiums that closing cost inflation could be masked. The Option ARM, among others, stepped into the breach and here we are.

The comments to this thread will be choked with outraged mortgage brokers who will once again give you the same old story that “premium” closing cost credits are a god-send to us average schmucks who don’t have several grand sitting around to pay closing costs with, but who oughta get the benefit of lower rates just like the Big People, etc. They will tell you that there are too many “competitive pressures” preventing brokers and wholesalers from larding up settlement statements with both origination fees and a boat-load of “itemized” fees. They will tell you that there are all kinds of perfectly “legitimate” reasons why the final settlement statement you get has all these fees and charges on it that weren’t on the GFE, most of which are your fault for delaying the process or not following what you were told. They will tell that they shop around to get the best rate for you, and deserve to be compensated for that, but that it is the consumer’s responsibility to shop around for several shop-arounds so that they can assure themselves of getting the cheapest deal on the fees. They will tell you that while they don’t do it, retail lenders do it too, so we should stop picking on brokers.

My problem here is with the basic mechanism of, in essence, financing your closing costs in this way (by taking the higher rate to get the “credit” that reduces the amount of cash you bring to closing). It is simply ripe for abuse because there is (now) such a large segment of the borrower world who do not already have prime-quality fixed rate loans, who are desperately focused on monthly payment, not total cost over the term of a loan, and who simply do not have the basic financial skills necessary to do the cost/benefit analysis of fees versus interest rate, even if they could afford to pay three separate credit report fees at $40 a pop to several different brokers in order to amass several different GFEs so that they could find a way to save back the $80 in “wasted” fees and then some. Not to mention the fact that they are, as a group, generally the most susceptible to high-pressure sales tactics (this is true generally of a lot of people with heavy consumer debt and thus low FICOs; they are just incapable of saying “no” when the clerk at Macy’s offers “10% off today’s purchase with Instant Credit!”).

To be honest with you, too many people in this business do not fully understand its cost structure. There’s just a massive confusion all over the place about the difference between “financing costs that are paid up front at the closing of a loan” (as distinguished from interest charges that are paid in the future) and “settlement costs.” There are quite a few things you have to cough up money for at the settlement of a mortgage that are really “prepaid items,” not finance charges. For instance, the money you bring in to fund your tax and insurance escrow accounts. You have to pay real estate taxes and homeowner’s insurance anyway; you either pay it yourself once or twice a year or you pay it on the “installment plan” by paying your lender one-twelfth of it a month. In order to get an escrow account established up front, you’ll probably have to put two months or so worth of escrow payments in the account to start it out (because the annual bills will be due the first time before you’ve managed to make twelve payments, basically, given the lag between closing a loan and the first payment due date). Escrow funding is a relatively large-dollar item on most loans compared to things like a $75 tax service fee, but it’s not the kind of thing shopping around will do you any good with, since it is what it is (assuming lenders get their hands on a realistic estimate of RE taxes) and there’s no “markup” in it—it’s your money, the lender is just taking it up front as a deposit into your escrow account.

It is easy enough, unfortunately, to low-ball the estimated escrow funding amounts on a GFE while larding up on actual finance charges. If borrowers are only comparing this lender’s total to another lender’s total, they can be highly misled about who has the cheapest “closing costs.” And almost all lenders charge a higher rate (or more points) to borrowers who are allowed to get a “waiver” of escrow accounts. If you aren’t paying attention, you might be comparing a GFE from one lender that includes two months’ worth of tax and insurance payments in “closing costs” to a GFE from another lender that includes no escrow dollars but increases your interest rate by 12.5 bps.

The same thing goes, on a less expensive plane, with things like surveys and pest inspections. It might be a lender requirement that you get one of these things, and you might be willing to play dice with your hard-earned money by ignoring survey lines or signs of termite damage if you weren’t required not to by some lender. But the fact remains that (unless the lender is conspiring with the surveyor or exterminator/inspector to get a “kickback”) you’re paying for a real good or service there that doesn’t benefit the lender only. A tax service fee, on the other hand, benefits the lender and investor, not you. You will get your tax bills directly from the county; you don’t need to pay someone to track them. A tax service fee is a classic case of a “finance charge” in the regulatory sense: it is a cost you incur because you are financing the property, that you wouldn’t incur in a cash purchase of the same home. This is why mortgage insurance, unlike your homeowner’s insurance, is considered a “finance charge.”

There are other things you might pay at a mortgage settlement that are a little murkier, conceptually. You wouldn’t pay for a lender’s title insurance policy in a cash sale, but you would (if you were sane) pay for a title search and an owner’s policy. You wouldn’t pay for an attorney to prepare a deed of trust (a “mortgage”) in a cash sale, but you’d pay for a grant deed (otherwise you wouldn’t have legal ownership of the home you’re buying). Appraisal charges aren’t considered “finance charges” for regulatory purposes, on the assumption that a reasonably competent cash buyer would also get an appraisal, although I’m willing to bet that most people think of them as “finance charges” or things you wouldn’t have to pay if the lender didn’t make you and that benefit only the lender.

All this matters for regulatory purposes—the rules about how lenders disclose “finance charges” as distinct from “settlement costs”—but it also matters because there has for some time been something very important getting lost in discussions of “closing costs” or the cost of mortgage credit. A lot of those costs are real estate transaction costs. We have been hearing for years on end, during the boom, that people “who are only going to stay in the house for two years” shouldn’t be “having to pay for a 30-year fixed rate.” We don’t hear many people wondering why you’d buy a home in that situation in the first place.

The reality in most markets across nearly any time period you care to name is that it’s almost never worth buying a house to live in for two years. It pretty much requires a bubble for the RE agent commission and the title search and the survey and the pest inspection and the deed recording fee and so on, let alone the true “finance charges,” to pay for themselves in two years. But there has been a shift in rhetoric and terminology that seems to lump “transaction costs” into “financing costs,” allowing people to “make sense of” buying a house you plan to live in for only two years because you can find some lender who will let you finance the transaction costs through this premium-rate “closing cost credit” deal.

The reality of things is that no lender makes any money charging premium interest rates to recover costs it didn’t charge the borrower at settlement if the borrower pays the loan off in a short period of time (unless it was a really really big premium). This is where your “prepayment penalties” came from; it’s also where all these expensive post-settlement fees (like the notorious fee for getting a payoff quote or a release of the old lien in a refi) come from. The economics of making “bridge loans” (short-term loans) at “permanent loan” terms just doesn’t work if you don’t collect fees up front. You can get by with a small enough percentage of your loans behaving like that—credit card lenders can get by with a small enough percentage of people who pay in full every month, and Best Buy can get by with a small enough percentage of people who do the “one year same as cash” thing and pay it off before a finance charge is imposed. But nobody can handle everybody behaving like that. Not for long.

And it’s not just home buyers, it’s refinances. It simply isn’t rational for an investor to “pay up” for a high interest rate if said loan is going to refinance at the next little market bump. But people will refinance, these days, for amazingly small rate increments, for two reasons. First, loans are a lot bigger than they used to be, while incomes haven’t been growing. That means that the dollars at stake in monthly payment savings become more significant even with small decreases in the interest rate.

The second reason is where this gets into a vicious cycle: people refinance at the drop of a hat because they don’t pay the closing costs in cash. They either roll the costs into the loan—driving balances up over time and creating even further incentive to refinance again—or they get that “premium credit” thing, which means that the borrower has a built-in incentive to refinance the new loan as quickly as possible. This dynamic creates regular income for brokers who get paid for each refi, but it doesn’t always do much for investors.

A great deal of this business over the last several years of refinancing people out of perfectly affordable fixed rate loans into these toxic ARMs came about because there was no longer any way to price a premium-rate fixed rate loan at a lower rate than what the borrowers already had. However, the market was full of “dumb money” that would pay 105 for a “high quality” Option ARM—not to mention the “low quality” ones. Many people focus on “YSP” as broker compensation, and that’s a big issue. Some of the sleazier brokers took those five points from the wholesaler and the borrower didn’t see a five point credit on the HUD-1. My point, though, is to question whether the ones who did get a closing credit really got such a great deal.

Would borrowers have balked at doing the refi to start with if they had had to pay at least some of the closing costs in cash? Would they have paid a touch more attention to those prepayment penalties they were signing up for if it had occurred to them that the only way a “no cost closing” can be profitable to a lender is by extending the life of the loan long enough for the costs to come out of the interest paid each month? Would borrowers have been more likely to catch on to an ARM masquerading as a fixed rate or nasty ARM terms “hidden” in a big pile of legalese if they had a realistic sense of how low 30-year fixed rates are likely to go on any given day? There is something terribly wrong with lenders who give out misleading disclosures, and I don’t blame borrowers for lender sleaziness. But there is also something terribly troubling about the apparent fact that a lot of people thought they were getting a 30-year fixed rate loan at 1.95%. That is much too good to be true. Why didn’t it occur to anyone that that’s much too good to be true?

To see this as strictly a “disclosure” issue is to simply cop out, as far as I’m concerned, on the question of a very old-fashioned view of what loan officers and brokers were supposed to be doing, which is explaining things like the fee/rate tradeoff, the point of prepayment penalties, and the likely range of prevailing market rates on fixed-rate loan quotes. “Educating” your borrowers is just off the table. All we’re left with is “disclosing” loan terms that truly educated borrowers probably wouldn’t have anything to do with, and relying on borrowers to “shop around” in a market in which they still have no idea what the “going rate” is.

We’ve gone, just in my career in this industry, from taking three whole business days to get a GFE into a consumer’s hands, because we did them with adding machines and typewriters and snail mail, to taking three whole minutes to do that with only reasonably fancy technology, and back to taking three whole days again because there are too many intermediaries in the process (all of whom have to get paid). And HUD is, after years and years of this practice going on, finally working up a way to disclose premium-rate closing cost credits right when the terrible market distortions partially due to that practice are melting down the credit markets. Behind the whole thing lurks the ideology that regulators are not there to tell anyone what is an allowable business practice; they’re there to just make sure you “disclose” what you’re up to. It is aided and abetted by a “consumer advocate” lobby who frequently seems to believe that “complexity of disclosures” is the problem, rather than unrealistic expectations consumers develop based on the onslaught of marketing they get from the industry, which tries to tell you there is a free lunch if you act now.

Once you and I have recovered from this post, we’ll look at some of the details of the new proposed GFE. I do hope it will make more sense after this ramble.

Friday, January 25, 2008

FirstFed: Delinquencies Up Sharply

by Calculated Risk on 1/25/2008 04:31:00 PM

From Housing Wire: Option ARM Specialist FirstFed: Delinquencies Up 231 Percent in One Quarter

... FirstFed said that option ARMs hitting a forced recapitalization were “a contributing factor in the higher level of delinquent loans.”Hitting the maximum level of negative amortization doesn't necessarily mean the homeowners will be in trouble. But the fear is that many of these homeowners used Option ARMs as affordability products (they could only buy the home making the neg-am payment), and that they will be in unable to make the payment when they no longer have the neg-am option.

During the fourth quarter of 2007, just over 1,800 borrowers, with loan balances of approximately $830 million, reached their maximum level of negative amortization and had a resulting increase in their required payment. The bank said that it estimated that another 2,400 loans totaling approximately $1.1 billion could hit their maximum allowable negative amortization during 2008.

Tuesday, January 15, 2008

FED: Just Another Quadrupling of Reserves

by Tanta on 1/15/2008 09:33:00 AM

SANTA MONICA, Calif., Jan 15, 2008 (BUSINESS WIRE) -- FirstFed Financial Corp., parent company of First Federal Bank of California, today announced that, due to rising single family loan delinquencies, the provision for loan losses for the current quarter is expected to be between $20 million and $23 million, compared with $4.5 million that was recorded for the third quarter of 2007.Who coodanode?

Non-accrual single family loans at December 31, 2007 rose to approximately $180 million, from $83 million at September 30, 2007, while single family loans thirty to eighty-nine days delinquent rose to approximately $237 million, from $72 million at September 30, 2007. Adjustable rate mortgages that have reached their maximum allowable negative amortization, which now require an increased payment, are a contributing factor in the higher level of delinquent loans.

Monday, January 14, 2008

OFHEO: Implications of Increasing the Conforming Loan Limit

by Calculated Risk on 1/14/2008 02:02:00 PM

OFHEO has released a preliminary analysis of the Potential Implications of Increasing the Conforming Loan Limit in High-Cost Areas.

The conforming loan limit is the maximum loan that Fannie and Freddie can buy. An overview:

For mortgages that finance one-unit properties, [the conforming loan] limit is $417,000 in 2008, as it was in 2006 and 2007. Higher limits apply to loans that finance properties with two to four units. The limits for properties of all sizes are 50 percent higher in Alaska, Hawaii, Guam, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. The limits are adjusted each year to reflect the change in the national average purchase price for all conventionally financed single-family homes, as measured by the Federal Housing Finance Board’s (FHFB’s) Monthly Interest Rate Survey (MIRS). Conventional single-family loans with original balances above the conforming loan limit are generally known as jumbo mortgages.And here is some interesting data on the Jumbo Market:

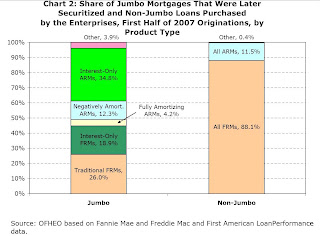

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.According to Inside Mortgage Finance Publications, originations of jumbo mortgages have ranged from 15 percent to 21 percent of the total single-family market from 2000 through the first half of 2007.Jumbo loans are not only larger, and geographically concentrated (almost 50% are in California!), but they also have many risky features:

...

The jumbo market is much more geographically concentrated than the conventional mortgage market as a whole. Data from First American LoanPerformance suggest that California accounted for 49 percent of the dollar volume of first lien jumbo mortgages originated in the first half of 2007 and later securitized (Chart 1). In a comparable sample of conventional loans purchased by the Enterprises, the California market share was 14 percent.

First American LoanPerformance data also suggest that interest-only (IO) loans and negatively-amortizing adjustable-rate mortgages (ARMs) comprised nearly two-thirds of the dollar volume of first lien jumbo loans originated in the first half of 2007 and later securitized, whereas traditional (fully amortizing) fixed-rate mortgages (FRMs) comprised only a quarter of those loans (Chart 2). In contrast, FRMs comprised over 88 percent of non-jumbo conventional loans originated in the first half of 2007 and purchased by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.With falling prices, many of these jumbo loans with IO or neg-Am features will probably be underwater soon. This will probably be a huge story in '08 and '09. (Note: There is much more in the OFHEO report).

Option ARM Update: "This is a stated income crisis"

by Tanta on 1/14/2008 10:26:00 AM

More pleasant news from the Platinum card crowd, courtesy of the LAT:

Option ARM delinquencies are at double-digit levels in many areas of California, including the Inland Empire. . . .

"This is not a sub-prime crisis. This is a stated income crisis," said Robert Simpson, chief executive of Investors Mortgage Asset Recovery Co. in Irvine, which works with lenders, insurers and investors to recover losses related to mortgage fraud. . . .

The percentage of option ARMs with payments behind by at least 60 days in California is in double digits in the Inland Empire, San Diego County, Santa Barbara County, Sacramento, Salinas and Modesto, according to data provided to The Times by mortgage researcher First American Loan Performance.

The more recent loans appear to be faring the worst, reaffirming the conclusion that lending standards had become overly lax throughout the mortgage industry in the middle of this decade, as competition for fewer good loans intensified amid skyrocketing home prices.

In Yuba City, north of Sacramento, 15% of option ARMs made in 2005 were delinquent at the end of October, the Loan Performance tally showed, and in Stockton-Lodi the delinquency rate on option ARMs from both 2005 and 2006 was over 13%.

"It is astonishing how fast the credit deterioration has occurred," said Paul Miller, an analyst with Friedman, Billings, Ramsey & Co. who follows the savings and loans that specialize in these mortgages. "It took me and everybody else by surprise."

Miller said Downey Financial Corp. was "the canary in the coal mine." The Newport Beach S&L has specialized in making option ARMs since the 1980s and keeps them as investments. Option ARMs make up about three-quarters of Downey's loan portfolio, with most of the rest being similar loans that allow interest-only payments during the first five years but don't allow the loan balance to rise.

Miller thought Downey had shown prudence in cutting back on lending in 2006, when home prices stopped rising and competition intensified from option ARM newcomers such as Countrywide and IndyMac Bancorp of Pasadena.

But a key indicator of loan troubles -- the ratio of nonperforming assets to total assets -- shot up from 0.55% to 3.65% at Downey over the last year, with the dud loans on Downey's books growing by $80 million in November, Miller said. That number, disclosed last month, was larger than the entire amount of non-performers Downey had a year earlier.

The quality of option ARMs appears to have deteriorated quickly when Wall Street began buying them to create mortgage bonds in the middle of this decade, drawing IndyMac, Countrywide and others into the business, Miller said.

Saturday, December 29, 2007

On Option ARMs

by Tanta on 12/29/2007 02:15:00 PM

This is a bonus post for those of you who use Excel (or some other software with which you can read and play with .xls files). I'm afraid that those of you who do not possess such software will have to use your imagination here. It's not especially practical to post images of big spreadsheets on the blog, so if you want to see the numbers, you'll need to download the spreadsheets.

These links will download the spreadsheets:

LIBOR-Indexed OA Projection

MTA-Indexed OA Projection

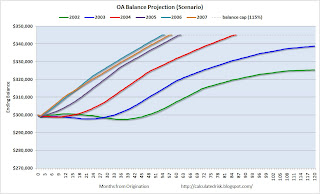

I made two of them for you to play with. Both show a to-date balance history, plus a future balance projection, for a hypothetical Option ARM with payments beginning in 2002, 2003, 2004, 2005, 2006, or 2007. The loan terms are identical for each spreadsheet with the exception of the index chosen: one uses MTA, the other 1-Month LIBOR. The terms of these scenarios are in fact derived from real loan products out there, but of course there are other ways of structuring OAs. I am not making a claim about what product structure was most common (or most likely still to be on the books), as I don't have that kind of data.

What I had in mind for this exercise is to help people see, clearly, how these things work (some folks are still, Lord love you, a bit confused about OA mechanics. That undoubtedly includes some of you who have one. Remember that if you do, your loan might not work like this because the note you signed might have different terms regarding adjustment frequency, balance cap, margin, etc.) Besides that, I wanted to make a fairly simple point about the issue of resets, payment shock, and timing on these things.

That's why the spreadsheets show multiple vintages with identical loan terms: you can see that the actual speed of negative amortization and the forecast date of recast on these loans varies quite dramatically for the vintages, because of the huge impact of the very low 2002-2003 rate cycle. Each of these scenarios assumes that the borrower always makes the minimum payment from inception of the loan, and each assumes that future index values are identical to the most recent available index value (December 2007). Yet even in those circumstances, the earlier loans (2002 and 2003, especially) negatively amortize much more slowly than the later vintages.

My gifted co-blogger has actually created some lovely charts to help make that clear:  Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.

If you've downloaded the spreadsheets, you can play around with them a little in terms of the future interest rates on these loans, and you can see how the recast date (the date the balance hits the balance cap and the loan payment must be recast to fully amortize over the remaining term) moves forward or back depending on what you do with the rates. This is one reason why modeling actual portfolios of OAs is such a challenge: you have to make assumptions about what will happen with the underlying index.

Of course, in actual portfolio modeling, you would also not assume that every borrower will always make the minimum payment. You would have to look at actual borrower performance to date, and calculate some "average" behavior or project each borrower's past behavior patterns into the future. I am not making the claim that all borrowers always make the minimum payment from inception; I'm trying to show what would happen, in some examples, if a borrower did that. I have heard estimates from different OA portfolios of anywhere from one-third to ninety percent of borrowers who have, historically, done that.

One other thing I wanted to make clear by providing these examples is the mechanics of payment increases for a very common OA type. The product shown in these spreadsheets allows for annual payment increases, but monthly rate increases. (That is how the potential for negative amortization gets created: the payment does not automatically adjust to match the new interest rate each month.) The eventual recast hits at the sooner of the loan reaching 115% of its original balance or 120 months. We know that a recast is nearly always a huge shock, given a low enough introductory rate. But this loan does involve payment increases of up to 7.5% each year (i.e., the next year's payment can be as much as 107.5% of the prior year's payment).

With the later vintage loans, especially, I for one have no confidence that the borrower was qualified at realistic enough original DTIs to withstand several years of payment increases, even before that nasty shock of the recast.

You may if you like change that introductory rate on these loans--I used 1.00%. You will see that increasing that introductory rate actually slows down the negative amortization in most scenarios. (That is because it creates a higher initial first year payment, which thus creates less of a shortfall between interest accrued and payment made.) I suspect that this fact about OA is surprising to some people, who think that folks who got a 1.00% "teaser" on these things got some real deal. In reality, a borrower who was given an introductory rate several points higher than that is probably doing much better, balance-wise.

My scenarios involve the assumption that the initial payment is fixed for only one year. There are OAs out there where the first payment change is two or even up to five years from the first payment date. (They will generally involve a higher introductory rate and margin.) You can change these spreadsheets to extend the original payment out for longer than a year, if you like, and you'll see just how much faster that balance cap hits when you extend the fixed payment period. Ouch.

Finally, while I chose the repayment periods I did quite arbitrarily, you will notice that for both the MTA and LIBOR scenarios, the most recent index value (December 2007) is substantially lower than it had been for quite some time. This means that my balance forecast here just happens to have picked up a relatively low last known index to project out into the future. Had we done this exercise several months ago, the projected future index value would have been higher, and hence the future negative amortization would have been faster. It's an issue to keep in mind as we look at portfolio and security projections regarding OA recasts; those will have to be updated from time to time as rate history unfolds.

And yes, there's a pig, if that makes you want to bother downloading the spreadsheets.

Friday, December 28, 2007

Option ARM Tightening

by Tanta on 12/28/2007 08:45:00 AM

A quite decent piece on Option ARMs in the LA Times. I liked this part:

Despite such risks, the initial low payments on option ARMs have kept a lid on serious delinquencies -- 3.7% of all option ARMs, Standard & Poor's analysts said in a report last week. That's higher than before, but still low compared with the 6.3% delinquency rate on loans to good-credit borrowers with so-called hybrid ARMs, which have a low fixed rate for two to 10 years before becoming adjustable-rate loans.I made an argument a while ago that focussing regulator attention exclusively on disclosure documents can be just a touch beside the point if lenders are no longer offering the product in question. You have to wonder, if we just cut off 80-90% of the OA borrower pool, whether the remaining 10% really need those new and improved disclosures, or can muddle along with the ones already in use. If you take the OA out of the mass market and put it back into the high-net worth, high-income crowd it was originally designed for, you might find that your borrowers are already selected to be people who either read and understand disclosures, or who hire an attorney or financial planner to read them. I can certainly think of better uses for regulators' time and energy than fooling around with disclosure documents that would be clear to borrowers who are now in a rather different kind of trouble than not understanding the teaser rate on their OA.

At Calabasas-based Countrywide Financial Corp., which S&P said made about a quarter of all option ARMs last year, 3% of such loans held by the lender as investments were delinquent at least 90 days, up tenfold from 0.3% a year earlier. Delinquency rates were even higher on option ARMs from other lenders, including Pasadena-based IndyMac Bancorp and Seattle's Washington Mutual Inc., S&P said.

Countrywide and other lenders tightened their lending standards last summer to ensure borrowers could afford loans after the interest rates adjusted upward.

Had those guidelines been in effect previously, Countrywide recently said, it would have rejected 89% of the option ARM loans it made in 2006, amounting to $64 billion, and $74 billion, or 83%, of those it made in 2005.

The other thing to notice is that the obligatory example borrower supplied in the article is having trouble with her first payment increase (the typical 7.5% annual increase in the minimum payment), which is still not enough to cover all the interest due. As that sort of situation increases (as more and more 2005-2006 vintage OAs get to their second or third payment increase), we'll start seeing defaults long before the recast date.

Speaking of which, when I am not making cartoon pigs I have been creating some spreadsheets to show examples of how to project the recast date on Option ARMs. That's total and compleat Nerd territory, but if anyone is interested I'll post them (as spreadsheets or as images thereof). You tell me whether that's more detail than you can stand or not.

Wednesday, October 31, 2007

Accounting For Negative Amortization

by Tanta on 10/31/2007 10:00:00 AM

Accounting for negative amortization is a perennial favorite amongst those who follow banks and thrifts with large Option ARM portfolios. It outrages a lot of folks that the neg am balances, which represent interest that has been earned but not paid, is considered noncash interest income. It also seems to outrage a lot of folks that OA portfolio holders do not simply declare these capitalized balances as "uncollectable." The idea seems to be that 1) the fact of negative amortization itself should mean that the loan is substandard or doubtful, regardless of timely payment of the contractually allowed minimum payment, and therefore 2) the accounting treatment for reserve purposes should be the much more onerous one, "all estimated credit losses over the remaining effective lives of these loans," rather than the standard for non-classified loans, "all estimated credit losses over the upcoming 12 months."

I think this is the argument Jonathan Weil is trying to make in this piece on WaMu:

As for the fourth quarter, Washington Mutual predicted that provisions would be $1.1 billion to $1.3 billion and that charge-offs would increase 20 percent to 40 percent.If you have any sense of how the OA market worked in the last three or four years, you have to find Weil's approach here a bit odd. Back in 2004-2005, when WaMu had more OAs on its books, it had younger OAs on its books. It takes some time for OAs to build up neg am balances, and as origination of this product really didn't take off until 2003-2004, you wouldn't expect any portfolio of OAs to have large capitalized balances for at least a few years.

To see why even $1.3 billion in provisions looks light, consider Washington Mutual's $57.86 billion of so-called option- ARM loans, which make up 24 percent of Washington Mutual's loan portfolio. These adjustable-rate mortgages were popular during the housing bubble, because they give customers the option of postponing interest payments, which the lender then adds to their principal balances.

As of Sept. 30, the unpaid principal balance on Washington Mutual's option ARMs exceeded the loans' original principal amount by $1.5 billion, meaning the customers owed $1.5 billion more in principal than what they originally borrowed. By comparison, that figure was $681 million a year earlier, when Washington Mutual had $67.14 billion, or 16 percent more, option ARMs on its books.

Look to the end of 2005, and the trend becomes even starker. Back then, Washington Mutual had even more option ARMs on its balance sheet, at $71.2 billion. Yet the unpaid principal balance exceeded the original principal amount by only $160 million -- and that was up from a mere $11 million at the end of 2004.

Deferring Pain

The deferred interest from option ARMs also boosts Washington Mutual's earnings, part of a process known as negative amortization, or ``neg-am.'' That's because option-ARM lenders recognize interest income when customers postpone their interest payments, even though the lenders got no cash.

For the nine months ended Sept. 30, Washington Mutual recognized $1.05 billion in earnings as a result of neg-am within its option-ARM portfolio. That represented 7.2 percent of Washington Mutual's $14.61 billion of total interest income year-to-date. By comparison, neg-am contributed 1.8 percent of Washington Mutual's interest income for all of 2005 and just 0.2 percent for 2004.

What's going on here? Either the borrowers postponing their interest payments are doing so as a matter of choice, by and large, or they can't afford to pay them. Common sense suggests it's the latter -- and that there's serious doubt Washington Mutual ever will collect the $1.5 billion of postponed interest that its option-ARM customers have added to their original principal balances.

What Weil is doing is trying to find a negative trend in the performance of these loans: his "common sense" says that the very fact of negative amortization means the borrowers are in trouble, and the very fact that neg am balances are growing in WaMu's portfolio means that a reasonable person would assume that this pattern should be projected into the foreseeable future. What that implies, of course, is that WaMu should "classify" all of these loans, regardless of LTV, timely payment, etc., on the recognized accounting basis of the "negative trend." If they did that, they would have to reserve a lot more against these loans, since allowances for classified loans are required, by the OTS, to be for the life of the loan. Reserves for nonclassified loans are for the next twelve months.

Yet the $1.1 billion to $1.3 billion of fourth-quarter provisions that Washington Mutual predicted -- for the company as a whole -- wouldn't even cover the $1.5 billion of tacked-on principal. The trend among Washington Mutual's option ARMs shows no sign of slowing, either.Surely not even the greatest OA skeptic believes that WaMu could conceivably face default of every last one of its OAs with a neg am balance in the next 12 months. Without saying so explicitly, Weil is suggesting that WaMu pack lifetime estimated losses on this portfolio into current reserves, for no other reason than that the loans are negatively amortizing.

Through a spokeswoman, Libby Hutchinson, Washington Mutual officials declined to comment. She said the company's executives aren't fielding questions until their next meeting with investors on Nov. 7.

Then there's the bigger picture. While Washington Mutual's loan-loss allowance rose 22 percent to $1.89 billion during the 12 months ended Sept. 30, nonperforming assets rose 128 percent to $5.45 billion. So even if Washington Mutual adds $1.3 billion in provisions next quarter, its loan-loss allowance still won't be anywhere close to catching up.

To be sure, Washington Mutual executives have some latitude over the timing of the company's loan-loss provisions. Yet they also may have a monetary incentive to push losses into 2008.

To me, that is the crux of all of this upset over OA accounting. I personally would not make OAs nor would I hold them in any portfolio over which I had control, so don't think I'm defending the product. However, we just went through a major regulatory effort on "nontraditional mortgage products," and the upshot of that was that the regulators did not and would not deem the negative amortization ARM an unacceptable product for depositories, in and of itself. There is plenty in the Nontraditional Mortgage Guidance about what underwriting practices and so on should be followed with these loans, and certainly the guidance isn't a carte blanche for writing any old dumb OA an institution can think of. But they are not, explicitly, "classified" just because they're OAs:

When establishing an appropriate ALLL and considering the adequacy of capital, institutions should segment their nontraditional mortgage loan portfolios into pools with similar credit risk characteristics. The basic segments typically include collateral and loan characteristics, geographic concentrations, and borrower qualifying attributes. Segments could also differentiate loans by payment and portfolio characteristics, such as loans on which borrowers usually make only minimum payments, mortgages with existing balances above original balances, and mortgages subject to sizable payment shock. The objective is to identify credit quality indicators that affect collectibility for ALLL measurement purposes.I do not know how to read this except that there must be specific indicators of credit quality in the analysis besides the fact that the loans are "nontraditional" and that the issue is capital adequacy, not just reserves (capital being expected to cover long-horizon potential losses, and reserves being expected to, well, cover the short term). Weil's "common sense" may tell him that neg am = loan distress by definition, but the regulators' common sense didn't tell them that, and whose common sense do you think matters to WaMu?

What this means is that the federal regulators have said that the fact that a loan accrues neg am balances does not, in and of itself, make the loan unacceptable, substandard, or uncollectable. How, precisely, banks are supposed to get away with reserving for them as if they were beats me: the regulators can get on your case just as much for over-reserving as for under-reserving, as this can smack of "cookie jar" accounting. The only way a bank could defend itself against the charge of over-reserving would be for it to define OAs as unacceptable as a product, without regard to any other facts or characteristics. Why does Weil or anyone else expect an originator of OAs to do this?

Similarly with the issue of treating neg am as income: what else would you treat it as? To argue that deferred interest is never in fact collectable is to argue that OAs always default and the recovery is never enough to cover the balance due. If you believed that to be true, you would never make such loans.

And the issue of a "trend" suffers from the same problems. OAs allow for negative amortization up to some limit. That is established in the legal documents when the loan is closed. When you make those loans, you must assume that any and all borrowers may elect to make the minimum payment. That means that a "trend" over time will occur in a highly predictable way, known as an "amortization schedule." Certainly some industry participants have expressed some pearl-clutching surprise over the fact that making the minimum payment seems to be near-universal among outstanding OA loans, but we can file that under the "stunned but not surprised" heading. You do not make neg am loans unless you're prepared for neg am.

The point: the accounting treatment for these loans--reserves, asset classification, income--isn't going to change as long as they're "legal." And nobody is going to reserve for an OA portfolio today assuming that it will be a total loss in the next twelve months. And nobody is going to stop treating accrued but unpaid interest as income. If you have problems with that--and you surely might--then what you have problems with is allowing banks and thrifts to originate and hold these loans tout court, because you have implicitly defined them as substandard to the extent that they do what they are designed to do.

I realize that it is, in some quarters, more entertaining to speculate about accounting shenannigans than it is to face up to the implications of your rhetoric, but there it is. If you want OAs to be illegal, say so, and let me know what happens when the free-marketers jump all over your case. Otherwise, this business of implying that WaMu is reserving against its performing OA portfolio only for losses expected in the next twelve months because it's playing bonus games, not because that's what the reserve rules are, is really disingenuous.

One can make the case that it is simply impossible to accurately treat a portfolio of OAs: they're either always under-reserved or always over-reserved. Fine. I have some sympathy with that argument. But it's an argument for the abolition of OAs, not a criticism of any one bank's application of accounting rules. In any case, I challenge anyone who has a problem with WaMu's accounting for its OA portfolio, but who does not think the product should be outlawed, to explain to me what it is you do want.

Tuesday, October 30, 2007

Option ARM Performance

by Tanta on 10/30/2007 10:20:00 AM

Bank of America has kindly given us permission to quote from its Weekly RMBS Trading Desk Strategy Report of October 26 (not online). The subject of this report is Option ARM performance, and the results are rather grim. While OAs are still performing better than Alt-A ARMs of the same vintage, the trends are, well, ugly. Bear in mind that the overwhelming majority of Alt-A ARMs in these two vintages have not yet experienced a rate reset (less than 10% of Alt-A ARMs in 2005-2006 had an initial fixed period of less than 3 years). So while the Alt-A ARM borrowers are making a higher payment than the OA borrowers, they are not yet experiencing payment shock.

While OAs are still performing better than Alt-A ARMs of the same vintage, the trends are, well, ugly. Bear in mind that the overwhelming majority of Alt-A ARMs in these two vintages have not yet experienced a rate reset (less than 10% of Alt-A ARMs in 2005-2006 had an initial fixed period of less than 3 years). So while the Alt-A ARM borrowers are making a higher payment than the OA borrowers, they are not yet experiencing payment shock. But while OAs may be performing better than Alt-A ARMs in recent vintages, their current performance compared to past vintages of OA is gruesome. This chart and the following one break out OAs by loan size and loan purpose, and they suggest that neither factor is driving the current delinquency spike in the 2005-2006 OA vintages. It's important to remember, of course, that the pre-2005 pools of OAs are tiny compared to the later ones. According to UBS, gross issuance of securitized OA pools was $18.5 billion in 2004, $128 billion in 2005, and $175 billion in 2006.

But while OAs may be performing better than Alt-A ARMs in recent vintages, their current performance compared to past vintages of OA is gruesome. This chart and the following one break out OAs by loan size and loan purpose, and they suggest that neither factor is driving the current delinquency spike in the 2005-2006 OA vintages. It's important to remember, of course, that the pre-2005 pools of OAs are tiny compared to the later ones. According to UBS, gross issuance of securitized OA pools was $18.5 billion in 2004, $128 billion in 2005, and $175 billion in 2006. It's hard to escape the conclusion that the "mass marketization" of the negative amortization loan product hasn't done much for its performance. BoA also reports that prepayment speeds have slowed dramatically for outstanding OAs, including those with and without prepayment penalties (or with expired prepayment penalties). That suggests that a fair number of these loans will be around long enough to test "historical" assumptions about what happens when their payments finally recast.

It's hard to escape the conclusion that the "mass marketization" of the negative amortization loan product hasn't done much for its performance. BoA also reports that prepayment speeds have slowed dramatically for outstanding OAs, including those with and without prepayment penalties (or with expired prepayment penalties). That suggests that a fair number of these loans will be around long enough to test "historical" assumptions about what happens when their payments finally recast.

Monday, October 29, 2007

Meanwhile, on the Option ARM Front

by Tanta on 10/29/2007 09:56:00 AM

Lenders continue diligently to seek out new customers eager to trade home equity for entrance into the "upscale subprime" class.

From the LA Times:

Sunwest's president and co-owner, Jason Hayes Evans, didn't respond to requests to discuss his company's mailings. But a salesman at Sunwest, describing it as staffed by capable mortgage veterans who survived the industry shakeout, said everyone at the brokerage took pains to carefully explain to borrowers the risks as well as the benefits of option ARMs.This kind of reminds me of my favorite cheesecake recipe, which calls for two and a half pounds of cream cheese, six large eggs, and a half a pint of heavy cream, among other things. It's intended for people in perfect health and at an ideal body weight whose ancestors lived to be 100 and who only eat raw green veggies. Somehow it gets consumed down to the last crumb anyway.