by Calculated Risk on 12/24/2015 08:34:00 AM

Thursday, December 24, 2015

Weekly Initial Unemployment Claims decrease to 267,000

The DOL reported:

In the week ending December 19, the advance figure for seasonally adjusted initial claims was 267,000, a decrease of 5,000 from the previous week's revised level. The previous week's level was revised up by 1,000 from 271,000 to 272,000. The 4-week moving average was 272,500, an increase of 1,750 from the previous week's revised average. The previous week's average was revised up by 250 from 270,500 to 270,750.The previous week was revised up to 272,000.

There were no special factors impacting this week's initial claims.

The following graph shows the 4-week moving average of weekly claims since 1971.

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.The dashed line on the graph is the current 4-week average. The four-week average of weekly unemployment claims increased to 272,500.

This was below the consensus forecast of 270,000, and the low level of the 4-week average suggests few layoffs.

Average weekly unemployment claims in 2015 will be the lowest in over 40 years (when the workforce was much smaller).

Wednesday, December 23, 2015

Quintessential Tanta: Reflections on Alt-A (with a Donald Trump mention)

by Calculated Risk on 12/23/2015 04:42:00 PM

CR Note: Joe Weisenthal at Bloomberg Odd Lots wrote about Tanta this week (my former co-blogger): How One Woman Tried To Warn Everyone About The Housing Crash

Or as Bloomberg's Tracy Alloway tweeted: "Big Short be damned. Listen to the conversation @TheStalwart and I had with @calculatedrisk about who saw it coming"

Here is a quintessential Tanta piece that really explains mortgage lending.

And there is even a Donald Trump mention:

What is so dishonest about the association of "subprime" and "poor people" is that it simply erases the fact that a lot of rich people have terrible credit histories and a lot of poor people have never even used credit. The "classic" subprime borrower is Donald Trump as much as it is "Joe Sixpack."Tanta Vive!!!

From Doris "Tanta" Dungey, written August 8, 2008: Reflections on Alt-A

Since for media and headline purposes "Alt-A" is the new subprime--the most recent formerly-obscure mortgage lending inside-baseball term to become a part of every casual news consumer's working vocabulary--it seems like a good time to pause for some reflection on what the term might mean. Much of this exercise will be merely for archival purposes, as "Alt-A" is now pretty much officially dead as a product offering and is highly unlikely to return as "Alt-A." Eventually, after the bust works itself out and the economy leaves recession and the bankers crawl out from under their desks and stretch out those limbs that have been cramped into the fetal position, a kind of "not quite quite" lending will certainly return. I am in no way suggesting that the mortgage business has entered the Straight and Narrow Path and is going to stay on it forever because we have Learned Our Lessons. Credit cycles--not to mention institutional memories and economies like ours--don't work that way. It's just that whatever loosened lending re-emerges après le deluge will not be called "Alt-A."

Subprime will eventually come back, too. The difference is that it will come back--in some modified form--called "subprime." That term is too old, too familiar, too, well, plain to ever go away, I suspect. "Subprime" is a term invented by wonky credit analysts, not marketing departments. It is not catchy. It is not flattering nor is it euphemistic. You may console yourself if your children "have special needs" rather than "are academically below average." If you get a subprime loan, you may console yourself that you got some money from some lender, but you can't avoid the discomfort of having been labelled below-grade.

Actually, the term "B&C Lending" used to be quite popular for what we now universally refer to as "subprime." (It was also called "subprime" in those days, too. We didn't have to pick one term because nobody in the media was paying any attention to us back then and there were no blogs and even if there had been blogs if you had suggested that a blog would generate advertising revenue by talking about the nitty-gritty of the mortgage business you would have been involuntarily institutionalized.) In mortgages as in meat, "prime" meant a letter grade of A. These were the pre-FICO days, when "credit quality" was determined by fitting loans into a matrix involving a host of factors--whether you paid your bills on time, how much you owed, whether you had ever experienced a bankruptcy or a foreclosure or a collection or charge-off, etc. "B&C lending" encompassed the then-allowable range of sub-prime loans that could be made in the respectable or marginally respectable mortgage business. It was always possible to find a "D" borrower, but that was strictly in the "hard money" business: private rather than institutional lenders, interest rates that would make Vinny the Loan Shark green with envy. "F" was simply a borrower no one--not even the hard-money lenders--would lend to.

As in the academic world, of course, there was always the problem of grade inflation and too many fine distinctions. You had your "A Minus," which is actually the term Freddie Mac settled on back in the late 90s for its first foray into the higher reaches of subprime. Discussing the difference between "A Minus" and "B Plus" was just one of those otiose pastimes weary mortgage bankers got into over drinks at the hotel bar when the conversational possibilities of angels dancing on the head of a pin or whether "down payment" was one word or two had been exhausted. More or less everyone agreed that there wasn't but a tiny smidgen of difference between the two, except that "A Minus" sounded better. Same with the term "near prime," which wasn't uncommon but never became as popular as "A Minus." "Near prime" is also "near subprime." "A Minus" completed the illusion that it was nearer the A than the B, even if the distances involved were sometimes hard to see with the naked eye.

But all of that grading and labelling was still basically limited to considerations of the credit quality of the borrower, understood to mean the borrower's past history of handing debt. Residential mortgage lending never, of course, limited itself to considering creditworthiness; we always had "Three C's": creditworthiness, capacity, and collateral. "Capacity" meant establishing that the borrower had sufficient current income or other assets to carry the debt payments. "Collateral" meant establishing that the house was worth at least the loan amount--that it fully secured the debt. It was universally considered that these three things, the C's, were analytically and practically separable.

That, I think, is very hard for people today to understand. The major accomplishment of last five to eight years, mortgage-lendingwise, has been to entirely erase the C distinctions and in fact to mostly conflate them. For the last couple of years, for instance, you would routinely read in the papers that "subprime" meant loans made to low-income people. Or it meant loans made to people who couldn't make a down payment or who borrowed more than the value of their property--that is, whose loans were very likely to be under-collateralized. This kind of characterization of subprime always struck us old-timer insiders as bizarre, but it seems to have made sense to the rest of the world and it stuck. After all, the media didn't really care about or even notice this thing called "subprime" until it began to be obvious that it was going to end really really badly. It therefore seemed perfectly obvious to a lot of folks that it must primarily involve poor people who borrow too much.

Those of us who were there at the time tend to remember this differently. In the old model of the Three C's, a loan had to meet minimum requirements for each C in order to get made. We didn't do two out of three. The only lenders who ever did one out of three were precisely those "hard money" lenders, who cared only about the value of the collateral. This was because they mostly planned on repossessing it. Institutional lenders' business plan still involved making your money by getting paid back in dollars for the loans you made, not by taking title to real estate and selling it.

The difference between a prime and a subprime lender was simply how low you set the bar for one of the C's, creditworthiness. Unless you were a hard-money lender, you expected to be paid back, so you never lowered the bar on capacity: everybody had to have some source of cash flow to make loan payments with. Traditional institutional subprime mortgage lenders were even more anal-compulsive about collateral than prime lenders were, a fact that probably surprises most people. Until very recently, historically speaking, institutional subprime lending involved very low LTVs and probably the lowest rate of appraisal fraud or foolishness in the business.

That isn't so surprising if you think about the concept of "risk layering," which is also an industry term. In days gone by, with the three C's, you didn't "layer" risk. If the creditworthiness grade was less than "A," then the capacity grade and the collateral grade had to be "summa cum laude" in order to balance the loan risk. It wasn't until well into the bubble years that anybody seriously put forth the idea that you could make a loan that got a "B" on credit and a "B" on capacity and a "B" on collateral and expect not to lose money.

Of course there has always been a connection between creditworthiness and capacity. Most Americans will pay back their debts as agreed unless they experience a loss of income. People rack up "B&C" credit histories most commonly after they have been laid off, fired, disabled, divorced, or just generally lost income. But this was true at any original income level: upper-middle-class people can lose income and become "B&C" credits. Lower-income folks may well be most vulnerable to income loss--first fired, first "globalized"--but then lower-income folks until recently had smaller debts to pay back out of reduced income, too. What is so dishonest about the association of "subprime" and "poor people" is that it simply erases the fact that a lot of rich people have terrible credit histories and a lot of poor people have never even used credit. The "classic" subprime borrower is Donald Trump as much as it is "Joe Sixpack."

Traditional subprime lending was what you might think of as "recovery" lending. That is, while the borrower's past credit problems were due to some interruption in income or catastrophic loss of cash assets with which to service existing debts, the subprime lenders didn't enter your picture until you had re-established some income. If you want to know what a "D" or "F" borrower was, it was basically someone still in the financial crisis--still unemployed, still underemployed, still unable to work. "B" and "C" borrowers had resumed income, but they still had a fresh pile of bad things on their credit reports--charge-offs, collections, bankruptcies. Prime lenders wouldn't make loans to these borrowers because even though they had resumed capacity, their recent credit history was too poor. Prime lenders want to you "re-establish" your credit history as well as your income, which pretty much means that those nasty credit events have to be several years old, on average, without recurrence in the most recent years, before you can be an "A" again. Absent subprime lenders, that means going without credit for those years.

This is where the idea came from--much promoted by subprime lenders during the boom--that subprime loans were intended to be fairly short-term kinds of financing that helped a borrower "re-establish" his or her creditworthiness. The whole rationale for the famous 2/28 ARM was that after two years of good payment history on that loan, the borrower could refinance into a prime loan and thus never have to pay the "exploding" interest rate at reset. (If you didn't keep up with the payments in the first two years, you were thus "still subprime" and deserved to pay that higher rate.) That was a perfectly fine rationale as long as subprime lenders used rational capacity and collateral requirements--reasonable DTIs during the early years of the loan, low LTVs--to make those loans. When all the "risk layering" started, it was less and less plausible that these borrowers would ever "become prime" in two years by making on-time mortgage payments, and what we got was a class of permanent subprime borrowers who survived by serial refinancing, each time into a lower "grade" loan product, until the final step of foreclosure.

You're probably still wondering what all this has to do with Alt-A. Alt-A is sort of a weird mirror-image of subprime lending. If subprime was traditionally about borrowers with good capacity and collateral but bad credit history, Alt-A was about borrowers with a good credit history but pretty iffy capacity and collateral. That is to say, while subprime makes some amount of sense, Alt-A never made any sense. It is a child of the bubble.

"Classic" subprime lending worked because, while it always charged borrowers a higher interest rate, it found a way to restructure payments such that the borrower's overall prospects for making regular payments improved. A classic "C" loan, for instance, was also called a "pre-foreclosure takeout." The borrower had had a period of reduced or no income, got seriously behind on her mortgage payment, and was facing loss of the house. Even though income had resumed, it wasn't enough to make up the arrearage while also making currently-due payments. So the subprime lender would refinance the loan, rolling the arrearage into the new loan amount, and offset the higher rate and larger balance with a longer term or some kind of "ramping up" structure. The "ramp-up," by the way, was not, historically, mostly by using ARMs. There were all kinds of old-fashioned exotic mortgages that you don't hear about any more, like the Graduated Payment Mortgage and the Step Loan and the Wraparound Mortgage and so on, all of which involved some way of starting off loans with a lower payment that slowly racheted up over three to five years or so into a fully-amortizing payment. It certainly wasn't always successful, but its intent was exactly to enable people to catch up on an arrearage and then actually begin to retire debt.

Alt-A, we are regularly told, is a kind of loan for people with good credit but weak capacity or collateral. It overwhelmingly involved the kind of "affordability product" like ARMs and interest only and negative amortization and 40-year or 50-year terms that "ramps" payment streams. But it doesn't do this in order to help anyone "catch up" on arrearages; people with good credit don't have any arrearages. Alt-A was and has always been about maximizing consumption, whether of housing or of all the other consumer goods you can spend "MEW" on. If subprime was supposed to be about taking a bad-credit borrower and working him back into a good-credit borrower, Alt-A was about taking a good-credit borrower and loading him up with enough debt to make him eventually subprime.

The utter fraudulence of the whole idea of Alt-A involves the suggestion that people who have managed debt in the past that was offered to them in the past on conservative "prime" terms must therefore be capable of managing debt in the future that is offered to them on lax terms. FICOs or traditional credit analyses are good predictors of future credit performance, but only if the usual terms of credit-granting are similar in the past and in the future. Think of it this way: subprime borrowers had proven that they couldn't carry 50 pounds, so the subprime lenders found a way to restructure their debts so that they were only carrying 40. Alt-A lenders took a lot of people who had proven they could carry 50 pounds and used that fact to justify adding another 50 pounds to the burden.

This has not worked out well.

The "Alt" in Alt-A is short for "alternative." Alt-A is one of the purest examples of a "new paradigm" thingy you can find. The conceit of Alt-A is that there is another way to approach "prime" lending that is equivalent in risk (assuming risk-based pricing) but--amazing!--way more painless. Toss out verifications of income and assets, and you are no longer evaluating capacity. Toss out down payments and careful formal appraisals and analysis of sales contracts and you are no longer evaluating collateral. But lookit that FICO!

A lot of folks see the failure of Alt-A as a failure of FICO scores. I don't see it that way. FICO scoring is just an automated and much more consistent way of measuring past credit history than sitting around with a ten-page credit report counting up late payments and calculating balance-to-limit ratios and subtracting for collection accounts and all that tedious stuff underwriters used to do with a pencil and legal pad. I have seen no compelling evidence that FICO scoring is any less reliable than the old-fashioned way of "scoring" credit history.

To me, the failure of Alt-A is the failure to represent reality of the view that people who have a track record of successfully managing modest amounts of debt will therefore do fine with very high amounts of debt. Obviously the whole thing was ultimately built on the assumption that house prices would rise forever and there would always be another refi. There was also the assumption that people are emotionally attached to their FICO scores--in more old-fashioned terms, that borrowers care about their "reputation" and don't want to ruin it by defaulting on a loan. The trouble with that assumption was that we were busy building a credit industry in which there was plentiful credit--on easy terms--for people with any FICO, any "reputation." A bad credit history is only a strong deterrent to default when credit is rationed, granted only to those with acceptable reputations, or--as in the case of "classic" subprime--granted only to those with poor reputations but strong capacity and collateral, and at a penalty rate. Unfortunately, the consumer focus (encouraged, of course, by the industry) on monthly payment rather than actual cost of credit meant that for a lot of people the fact of the "penalty rate" just didn't register. In such an environment, the fear of losing your good credit record isn't much of a deterrent to default.

I should point out that besides the "stated income" and no-down junk, the other big segment of the Alt-A pool was "nonstandard" collateral types. One of the biggies in that category were what insiders call "non-warrantable condos." (The warranties in question are the ones the GSEs force you to make when you sell a condo loan; in essence a non-warrantable condo means one the GSEs won't accept.) What was wrong with these condos? Not enough pre-sales. Not enough sales to owner-occupants rather than investors. Inadequately funded HOAs with absurd budgets. Big blocks of units owned by a single entity or individual. In other words, speculator bait. This kind of thing isn't an "alternative" to "A." It is commercial or margin lending masquerading as long-term residential mortgage lending. It may well be "prime" commercial lending. It just isn't residential mortgage lending.

Part of the terrible results of Alt-A lending is that this book took on risks that historically were taken only on the commercial side, where the rates were higher, the cash-flow analysis was better, and the LTVs a lot lower. (Not that commercial real estate lending didn't also have its dumb credit bubble, too.) The thing is, as long as the flipping of speculative purchases worked--and it did for several years--it worked. Meaning, those Alt-A loans prepaid quite quickly with no losses. That masked the reality of Alt-A--that it was largely a way for people to take on more debt than they ever had before--for quite some time.

Of course we all know now--I happen to think a lot of us knew then--that Alt-A is chock-full o' fraud. My point is that even without excessive "stated income" or appraisal fraud, the Alt-A model was essentially doomed. "Alt-A" is the kind of lending you would only do after a real estate bust, not during a real estate boom--that is, when housing costs and thus debt levels are dropping, not rising. Unfortunately, we're going to have a hard time using something like Alt-A to stimulate our way into recovery once the housing market has actually bottomed out, because Alt-A is too implicated in the bust. I don't think anyone is going to be allowed to get away with moving all that REO off their books by making loans on easy terms to someone who managed to maintain a good FICO during the bust, even though that might actually make some sense.

One of the main reasons we are in a mortgage credit crunch is that two possible models of "recovery" lending--subprime and Alt-A--got used up blowing the bubble. I think it will be a long time before lending standards ease significantly, and I think subprime will come back first. But I do suspect we've seen the last of Alt-A for a much longer time.

Philly Fed: State Coincident Indexes increased in 40 states in November

by Calculated Risk on 12/23/2015 02:42:00 PM

From the Philly Fed:

The Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia has released the coincident indexes for the 50 states for November 2015. In the past month, the indexes increased in 40 states, decreased in five, and remained stable in five, for a one-month diffusion index of 70. Over the past three months, the indexes increased in 44 states, decreased in five, and remained stable in one, for a three-month diffusion index of 78.Note: These are coincident indexes constructed from state employment data. An explanation from the Philly Fed:

The coincident indexes combine four state-level indicators to summarize current economic conditions in a single statistic. The four state-level variables in each coincident index are nonfarm payroll employment, average hours worked in manufacturing, the unemployment rate, and wage and salary disbursements deflated by the consumer price index (U.S. city average). The trend for each state’s index is set to the trend of its gross domestic product (GDP), so long-term growth in the state’s index matches long-term growth in its GDP.

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.This is a graph is of the number of states with one month increasing activity according to the Philly Fed. This graph includes states with minor increases (the Philly Fed lists as unchanged).

In November, 44 states had increasing activity (including minor increases).

Five states have seen declines over the last 6 months, in order they are North Dakota (worst), Wyoming, Alaska, Montana, and Louisiana - mostly due to the decline in oil prices.

Here is a map of the three month change in the Philly Fed state coincident indicators. This map was all red during the worst of the recession, and is mostly green now.

Here is a map of the three month change in the Philly Fed state coincident indicators. This map was all red during the worst of the recession, and is mostly green now. Source: Philly Fed.

Comments on November New Home Sales

by Calculated Risk on 12/23/2015 11:50:00 AM

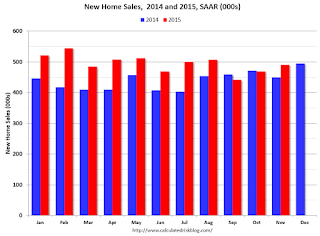

The new home sales report for October was somewhat below expectations, and sales for August, September and October were revised down. Sales were up 9.1% year-over-year in November (SA).

Earlier: New Home Sales increased to 490,000 Annual Rate in November.

Even though the November report was somewhat disappointing, sales are still up solidly year-to-date. The Census Bureau reported that new home sales this year, through November, were 461,000, not seasonally adjusted (NSA). That is up 14.5% from 402,000 sales during the same period of 2014 (NSA). That is a strong year-over-year gain for 2015 through November.

This graph shows new home sales for 2014 and 2015 by month (Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rate).

The year-over-year gains were stronger earlier this year, but the overall year-over-year gain should be solid in 2015. The comparisons in early 2016 will be more difficult.

Overall this was a solid year for new home sales.

And here is another update to the "distressing gap" graph that I first started posting a number of years ago to show the emerging gap caused by distressed sales. Now I'm looking for the gap to close over the next few years.

Following the housing bubble and bust, the "distressing gap" appeared mostly because of distressed sales.

I expect existing home sales to move more sideways, and I expect this gap to slowly close, mostly from an increase in new home sales.

However, this assumes that the builders will offer some smaller, less expensive homes.

Note: Existing home sales are counted when transactions are closed, and new home sales are counted when contracts are signed. So the timing of sales is different.

New Home Sales increased to 490,000 Annual Rate in November

by Calculated Risk on 12/23/2015 10:00:00 AM

The Census Bureau reports New Home Sales in November were at a seasonally adjusted annual rate (SAAR) of 490 thousand.

The previous three months were revised down by a total of 36 thousand (SAAR).

"Sales of new single-family houses in November 2015 were at a seasonally adjusted annual rate of 490,000, according to estimates released jointly today by the U.S. Census Bureau and the Department of Housing and Urban Development. This is 4.3 percent above the revised October rate of 470,000 and is 9.1 percent above the November 2014 estimate of 449,000"

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.The first graph shows New Home Sales vs. recessions since 1963. The dashed line is the current sales rate.

Even with the increase in sales since the bottom, new home sales are still fairly low historically.

The second graph shows New Home Months of Supply.

The months of supply decreased in November to 5.7 months.

The months of supply decreased in November to 5.7 months. The all time record was 12.1 months of supply in January 2009.

This is now in the normal range (less than 6 months supply is normal).

"The seasonally adjusted estimate of new houses for sale at the end of November was 232,000. This represents a supply of 5.7 months at the current sales rate."

On inventory, according to the Census Bureau:

On inventory, according to the Census Bureau: "A house is considered for sale when a permit to build has been issued in permit-issuing places or work has begun on the footings or foundation in nonpermit areas and a sales contract has not been signed nor a deposit accepted."Starting in 1973 the Census Bureau broke this down into three categories: Not Started, Under Construction, and Completed.

The third graph shows the three categories of inventory starting in 1973.

The inventory of completed homes for sale is still low, and the combined total of completed and under construction is also low.

The last graph shows sales NSA (monthly sales, not seasonally adjusted annual rate).

The last graph shows sales NSA (monthly sales, not seasonally adjusted annual rate).In November 2015 (red column), 34 thousand new homes were sold (NSA). Last year 31 thousand homes were sold in November.

The all time high for November was 86 thousand in 2005, and the all time low for November was 20 thousand in 2010.

This was below expectations of 503,000 sales SAAR in November, and prior months were revised down - a somewhat disappointing report. I'll have more later today.

Personal Income increased 0.3% in November, Spending increased 0.3%

by Calculated Risk on 12/23/2015 08:30:00 AM

Note: Some of this data was inadvertently released early. The BEA released the Personal Income and Outlays report for November:

Personal income increased $44.4 billion, or 0.3 percent, ... according to the Bureau of Economic Analysis. Personal consumption expenditures (PCE) increased $40.1 billion, or 0.3 percent.The following graph shows real Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) through November 2015 (2009 dollars). Note that the y-axis doesn't start at zero to better show the change.

...

Real PCE -- PCE adjusted to remove price changes -- increased 0.3 percent in November, in contrast to a decrease of less than 0.1 percent in October. ... The price index for PCE increased less than 0.1 percent in November, compared with an increase of 0.1 percent in October. The PCE price index, excluding food and energy, increased 0.1 percent, compared with an increase of less than 0.1 percent.

The November PCE price index increased 0.4 percent from November a year ago. The November PCE price index, excluding food and energy, increased 1.3 percent from November a year ago.

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.The dashed red lines are the quarterly levels for real PCE.

The increase in personal income was larger than expected. And the increase in PCE was at the 0.3% increase consensus.

On inflation: The PCE price index increased 0.4 percent year-over-year due to the sharp decline in oil prices. The core PCE price index (excluding food and energy) increased 1.3 percent year-over-year in November.

Using the two-month method to estimate Q3 PCE growth, PCE was increasing at a 2.1% annual rate in Q3 2015 (using the mid-month method, PCE was increasing 2.0%). This suggests PCE growth will slow in Q4.

MBA: Mortgage Applications Increase in Latest MBA Weekly Survey, Purchase Applications up 37% YoY

by Calculated Risk on 12/23/2015 07:01:00 AM

From the MBA: Refinance, Purchase Applications Both Up in Latest MBA Weekly Survey

Mortgage applications increased 7.3 percent from one week earlier, according to data from the Mortgage Bankers Association’s (MBA) Weekly Mortgage Applications Survey for the week ending December 18, 2015.

...

The Refinance Index increased 11 percent from the previous week. The seasonally adjusted Purchase Index increased 4 percent from one week earlier. The unadjusted Purchase Index increased 2 percent compared with the previous week and was 37 percent higher than the same week one year ago.

The average contract interest rate for 30-year fixed-rate mortgages with conforming loan balances ($417,000 or less) increased to 4.16 percent from 4.14 percent, with points increasing to 0.47 from 0.45 (including the origination fee) for 80 percent loan-to-value ratio (LTV) loans.

emphasis added

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.The first graph shows the refinance index.

Refinance activity remains low.

2014 was the lowest year for refinance activity since year 2000, and 2015 was low too. Refinance activity will probably stay low in 2016.

The second graph shows the MBA mortgage purchase index.

The second graph shows the MBA mortgage purchase index. According to the MBA, the unadjusted purchase index is 37% higher than a year ago.

Tuesday, December 22, 2015

Wednesday: New Home Sales, Durable Goods, Personal Income and Outlays and More

by Calculated Risk on 12/22/2015 07:24:00 PM

From Matt Busigin at Macrofugue: US Recession Callers Are Embarrassing Themselves

Through a combination of quackery, charlatanism, and inadequate utilisation of mathematics, callers for US recession in 2016 are embarrassing themselves. Again.CR Note: Usually there is a reason for a recession such as a bursting bubble or the Fed tightening quickly to fight inflation. Currently the recession callers seem to focus mostly on global weakness and the strong dollar. That has pushed U.S. manufacturing into contraction (along with low oil prices), but I don't think it will push the US economy into recession. Oh well, someone is always predicting a recession and they are usually wrong (I did forecast a recession in 2007, but I was on recession watch because of the housing bubble). Right now I'm not even on recession watch.

The most prominent reason for recession calling may well be the Institute of Supply Management’s Manufacturing Purchasing Manager Index. The problem with this recession forecasting methodology is that it doesn’t work.

Wednesday:

• At 7:00 AM ET, the Mortgage Bankers Association (MBA) will release the results for the mortgage purchase applications index.

• At 8:30 AM, Durable Goods Orders for November from the Census Bureau. The consensus is for a 0.5% decrease in durable goods orders.

• Also at 8:30 AM, Personal Income and Outlays for November. The consensus is for a 0.2% increase in personal income, and for a 0.3% increase in personal spending. And for the Core PCE price index to increase 0.1%.

• At 10:00 AM, New Home Sales for November from the Census Bureau. The consensus is for a increase in sales to 503 thousand Seasonally Adjusted Annual Rate (SAAR) in November from 495 thousand in October.

• Also at 10:00 AM, University of Michigan's Consumer sentiment index (final for December). The consensus is for a reading of 91.9, up from the preliminary reading 91.8.

Chemical Activity Barometer "Chemical Activity Barometer Ends Year with Modest Uptick"

by Calculated Risk on 12/22/2015 03:12:00 PM

Here is an indicator that I'm following that appears to be a leading indicator for industrial production.

From the American Chemistry Council: Chemical Activity Barometer Ends Year with Modest Uptick

The Chemical Activity Barometer (CAB), a leading economic indicator created by the American Chemistry Council (ACC), strengthened slightly in December, rising 0.2 percent following a similar gain in November. All data is measured on a three-month moving average (3MMA). Accounting for adjustments, the CAB remains up 1.5 percent over this time last year, a marked deceleration of activity since the second quarter....

...

Applying the CAB back to 1919, it has been shown to provide a lead of two to 14 months, with an average lead of eight months at cycle peaks as determined by the National Bureau of Economic Research. The median lead was also eight months. At business cycle troughs, the CAB leads by one to seven months, with an average lead of four months. The median lead was three months. The CAB is rebased to the average lead (in months) of an average 100 in the base year (the year 2012 was used) of a reference time series. The latter is the Federal Reserve’s Industrial Production Index.

emphasis added

Click on graph for larger image.

Click on graph for larger image.This graph shows the year-over-year change in the 3-month moving average for the Chemical Activity Barometer compared to Industrial Production. It does appear that CAB (red) generally leads Industrial Production (blue).

This suggests that industrial production might have stabilized.

A Few Random Comments on November Existing Home Sales

by Calculated Risk on 12/22/2015 11:55:00 AM

First, the decline in existing home sales was not a surprise, see: Existing Home Sales: Take the Under Tomorrow

Second, a key reason for the decline was the new TILA-RESPA Integrated Disclosure (TRID). In early October, this new disclosure rule pushed down mortgage applications sharply - however applications have since bounced back. Note: TILA: Truth in Lending Act, and RESPA: the Real Estate Settlement Procedures Act of 1974. The impact from TRID will sort out over a few months.

Third, there are probably some economic reasons too for the decline (not just a change in disclosures). Low inventory is probably holding down sales in many areas, and weakness in some oil producing areas (see: Houston has a problem) are also impacting sales.

Earlier: Existing Home Sales declined in November to 4.76 million SAAR

I expected some increase in inventory this year, but that hasn't happened. Inventory is still very low and falling year-over-year (down 1.9% year-over-year in November). More inventory would probably mean smaller price increases and slightly higher sales, and less inventory means lower sales and somewhat larger price increases.

Also, it is important to remember that new home sales are more important for jobs and the economy than existing home sales. Since existing sales are existing stock, the only direct contribution to GDP is the broker's commission. There is usually some additional spending with an existing home purchase - new furniture, etc - but overall the economic impact is small compared to a new home sale. So some slowing for existing home sales is not be a big deal for the economy.

The following graph shows existing home sales Not Seasonally Adjusted (NSA).

Sales NSA in November (red column) were the same as last year, matching the lowest for November since 2011 (NSA).